views

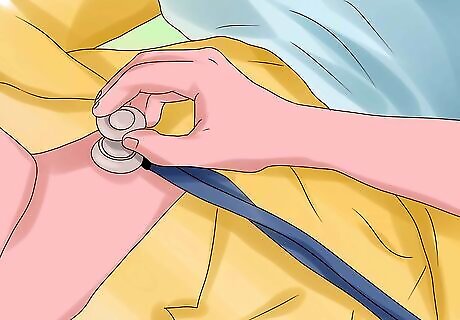

Understand how an ICD works. There are two main parts that make up the device: the leads, which are thin wire electrodes attached to your heart that monitor the rhythm, and the generator (often referred to as the actual ICD), which provides and delivers the electricity during a shock. Most ICDs also have a pacemaker function, as well. The electrodes are attached to your heart, either in one or both ventricles, and continuously monitor the electrical impulses of the heart. When it detects a potentially life-threatening rhythm (arrhythmia), the ICD will provide one of three possible treatments: Cardioversion: Giving a shock at a specific time during the cardiac cycle to try to convert the arrhythmia to a normal sinus rhythm (NSR). Defibrillation: Shocking a large mass of the heart muscle to depolarize it, reset the cells (therefore, terminating the arrhythmia), and allow the SA node to reestablish NSR. This procedure is often depicted in the media with paddles/pads and the patient violently jerking. Pacing: Using the built-in pacemaker, a series of short bursts of electricity are given in time with the heartbeat to slow it down.

Learn about your condition and the reason(s) why you need this device. People who survive cardiac arrests, have been diagnosed with an arrhythmia, and are at a high risk of sudden cardiac death are often candidates for an ICD implantation. Survivors of heart attacks may also get ICDs. The two arrhythmias that ICDs treat originate from the ventricles of the heart. These are: Ventricular tachycardia (V-tach/VT): An abnormally fast heart rate (over 100 beats per minute). This is treated with cardioversion if a pulse is found. However, if left untreated, it could degenerate into ventricular fibrillation (see below). Ventricular fibrillation (V-fib/VF): The heart muscle is uncontrollably contracting, making the heart quiver rather than pump blood. It is an extremely dangerous arrhythmia because blood flow to the brain is stopped, depriving it from oxygen. This is treated with defibrillation. However, if left untreated for more than a few seconds, it's likely to degenerate into asystole ("flatline"); brain damage and even death occurs if this continues for more than 5 minutes. Before the procedure, make sure that you fully understand your condition and the reason why an ICD is needed. Ask your doctors, read pamphlets, or even talk to other patients who have ICDs.

Adjust your arm movements in the first few weeks after the surgery. To promote wound healing, try not to raise your arm (of the affected side) high above your head. Do all such actions with your other hand.

Be prepared for changes. Although your lifestyle will remain unchanged, there are a few considerations you'll have to make. For example, you may have to adjust your seat belt shoulder harness if the ICD was implanted in your upper chest. If you find an item of clothing creates pressure around your upper chest, you may have to stop wearing it. Adjust your lifestyle according to such things becoming apparent to you when going about your normal activities.

Carry an ID card indicating you have an ICD. When you're having any procedure done, tell your doctor, dentist, or other health care professional about your ICD. Since it's made of metal, the ICD may set off metal detectors and other security devices found in airports and other places. Show your card to security personnel––keep it with your other travel documents for ease of retrieval.

When possible, stay away from anything that may cause interference to your ICD. This consists of objects emitting radio waves or magnetic fields. Often, you will receive a booklet containing a list of electronics to watch out for. Some examples include: MRIs (strongly avoid), radio-transmitting towers and ham radios. Common household items such as cell phones, kitchen appliances, microwaves, hairdryers, and electric blankets are safe to use as long as they are 6 inches (15 cm) away from the device.

Avoid rough sports that use constant body contact. Examples include football, wrestling, and boxing. Be alert and watch for any balls that could hit the implantation site. This may even include taking precautions as a spectator where there is a possibility that a ball could leave the field or pitch and end up in the audience area.

Beware of driving, especially within the first few months of implantation. You could suddenly become unconscious or startled when a shock appears, causing you to lose control of your car.

Respond calmly to shock experiences. A third to a half of ICD recipients experience an ICD shock in the first year of implantation. While it's likely that you'll be unconscious before the shock occurs, many patients often describe them as painful kicks to the chest. If you get a shock, contact your cardiologist promptly. Planning is vital for dealing with ICD shocks. Being aware that they're a possibility and knowing the difference between when you need to seek emergency help or to make a doctor's appointment is important for reassuring yourself about the effects of the shock. It is recommended that you discuss post-shock actions with your doctor or cardiologist and rehearse your response so that when it happens, it feels normal to respond in a certain way. Always have your ICD identification card and information with you or easily accessible, a list of your current medications and your doctor's contact details. This will reassure you and it can also help anyone else who needs to use the information to help you. Train your family and friends in what to do if you experience a shock. Explain to them what to look for when it happens and how they can help you. Having a supportive team with you can make an enormous difference to staying positive after the shock. Practice deep breathing and relaxing responses to help you to stay calm when shock occurs. Becoming hyper-aroused (such as panicking, shallow breathing, etc.) can escalate the impact unnecessarily. Some people recommended meditation as a daily action to help you stay mindful of your reactions to stressful situations. Seek help for psychological responses to ICD shock. It is normal to feel anxiety or depression, worry and fear with respect to an ICD shock. These psychological effects are often associated with the uncertainty of when a shock will appear or what the outcome of it might be (including fear of death). These fears will slowly decrease as you get more used to your ICD but it's important to get help through talking to people who can reassure you. For many people an ICD is better than no ICD; if and when a shock occurs, it is at least reminding you that you have the best care keeping you healthy. Consider your personal values, and ICD benefits and burdens, when deciding if an ICD is right for you.

Consider contingency plans in the event your health status changes. An ICD may be a good choice for you at one time in your life, but sometimes disease progression can make the ICD less beneficial. Discuss a plan for this possibility with your doctor, before the ICD is implanted.

Attend your regular appointments with your cardiologist. It is very important to get your ICD checked on a regular basis. During appointments, you will undergo an ECG to examine your heart's electrical activity. Depending on your condition, checkups may range from every 4-6 months to a yearly appointment. These times are also good for asking your doctor questions or if you have concerns.

Comments

0 comment