views

Performing Routine Maintenance and Cleaning

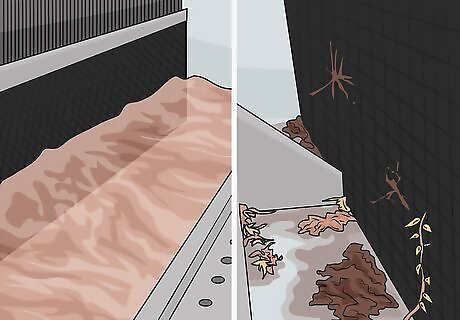

Remove all the dirt and debris in the cooling tower every day. Try to do a visual inspection of the cooling tower at the end of the day. If you see any dirt, debris, or slime at the top of the water, put on gloves and clean it out manually, taking caution not to dip your bare hands into the tank, as you could expose yourself to bacteria. Incorporate a visual inspection into your end of the day shut-down routine for the building.

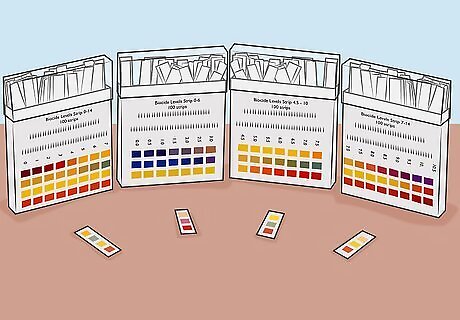

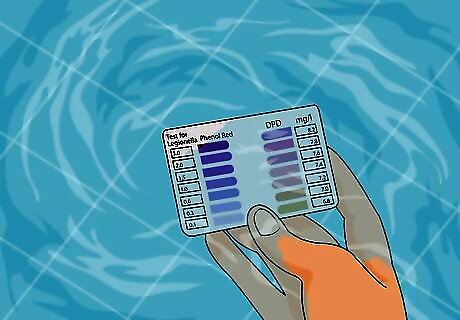

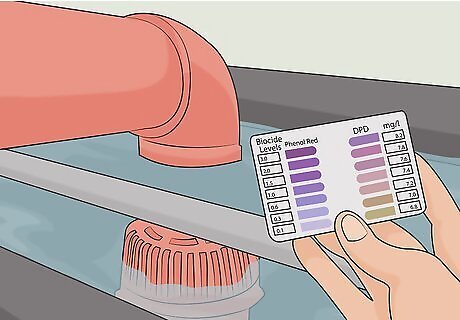

Check the chemical levels in the cooling tower once a week. Purchase test strips and make sure the chlorine and biocide levels are sufficient. For most cooling towers, the chlorine should be between 0.2 and 0.5 ppm, and the biocide levels should be between 30 and 50 ppm. If your chemical levels are high or low, check the manufacturer's recommendation on how to proceed. Most likely you will need to either flush your system or add more chemicals. Legionella can become resistant to biocide if you continually use the same strain, so consider switching up your biocide type once per year.

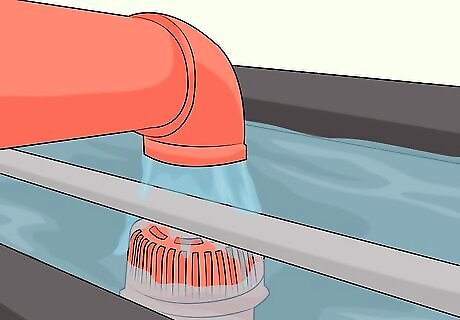

Circulate water throughout the entire system whenever it’s in operation. Stagnant water is a breeding ground for Legionella and other bacteria. If you can, make sure that your water system is constantly circulating through the cooling tower so that it doesn’t sit stagnant for more than a few hours at a time.

Drain the cooling tower if it’s off for more than 3 days. Stagnant water can breed bacteria, including Legionella. If your water system was shut down for an extended period of time, completely flush the system and allow it to fill back up with fresh water.

Clean and disinfect the cooling tower twice per year. Every 6 months, drain your cooling tower completely and wash it out with a non-oxidizing biocide. Then, refill it with clean water and dose it with biocide and chlorine at the appropriate levels for the size of your tower.Warning: Some municipalities have rules and regulations on how you can drain your cooling tower. Check with your local guidelines before you clean yours out. Check the cooling tower manufacturing instructions before you clean it out. If your cooling tower is not in constant use, you may need to clean it out once a week instead of twice per year since the water sits stagnant more often.

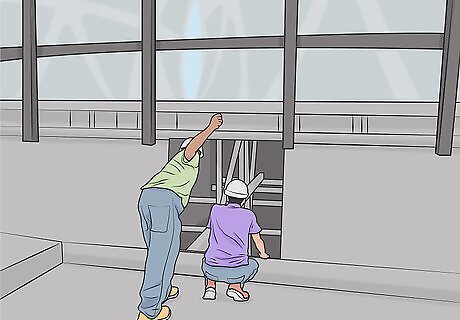

Inspect the cooling tower every 6 months for water drift. Most cooling towers come with shields to prevent water droplets drifting off as mist in the wind. Do a visual inspection twice a year to make sure your cooling tower is secure and that no water droplets are escaping. Legionella can live in water droplets, which is why it’s important to keep them contained. If you do have any water drift, you can either replace your shields or move your cooling tower away from any air intake valves.

Test for Legionella if an outbreak occurs. There are laboratory tests to show when a cooling tower is infected with Legionella, but you don’t need to use them regularly. If someone in your building gets sick with Legionella, contact a lab right away so you can get same-day results on the bacteria in your cooling tower and the rest of your water system. You shouldn’t test for Legionella regularly because most cooling towers contain a little bit of Legionella. It’s just usually not enough to do harm to anyone.

Creating a Water Management Program

Put together a water management team. Hotels, resorts, healthcare facilities, and other large buildings that send water to multiple floors and levels are at risk for Legionella in their cooling pipes. If you are in charge of a large building, assemble a water management team of 5 to 10 people so you can assign them daily, weekly, and monthly tasks based on the size of your building. This can include the building owner, the building manager, state or local health officials, and even biologists or environmental specialists. You may need to hire outside personnel if your building is at risk.

Sketch your water flow system in a diagram. Your water flow system is the path that the fresh water takes from the moment it enters your building to the moment it exists. It includes the heating, cooling, distributing, and discarding of all the water in your building, drinking water and non-drinking water included. Create a flow chart to track the path of your water at each stop that it makes.Warning: Be as specific and detailed as possible so you and your team know exactly what and where to check for Legionella. For example, your water could enter in from the water main in the basement and then distribute evenly between the fountain in the lobby, the cooling tower on the roof, the ice machines on each floor, the pool, and the showers on each floor. Additionally, the cool water may be heated in the water heaters and distributed to the sinks and showers on each floor. Finally, the water may be discarded through the sewer line. You may be able to find this information in existing building or plumbing blueprints.

Look for areas where Legionella could grow. Areas where water sits stagnant for a long time, areas that have low disinfection, areas where the temperature is low, or areas that come into contact with at-risk people are all places of concern. Mark these on your flow chart so you can give them special consideration in the future. People 65 and older or those with compromised immune systems are more at risk for legionnaires. Common areas of concern in buildings include showerheads, water heaters, cooling systems, and fountains.

Check the chemical levels and temperature of each area once per week. Depending on each risk factor, you may need to test the areas of potential Legionella as often as once per week. Assign members of your water management team to do visual inspections, temperature readings, and chemical tests as often as you need to.

Comments

0 comment