views

Coming Up With Ideas

Freewrite about whatever is on your mind. Songs are about anything -- romance, lost shoes, politics, depression, euphoria, school, etc. -- so don't worry about writing the "right" thing and just start scribbling. If you don't even want to rhyme the lyrics just yet, that's totally fine. Right now, you're just collecting ideas and material to work with later. When thinking of ideas, try to: Speak from the heart-- the things you really feel strongly about are usually the easiest to write lyrics for. Don't judge or throw out your work yet -- this is the drafting stage, you'll be perfecting as you keep writing.

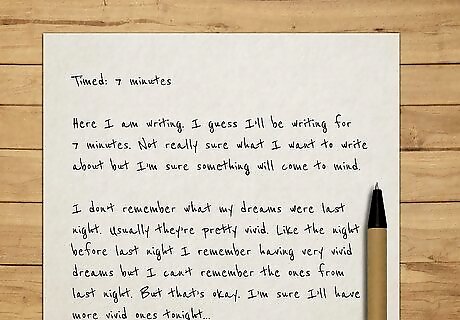

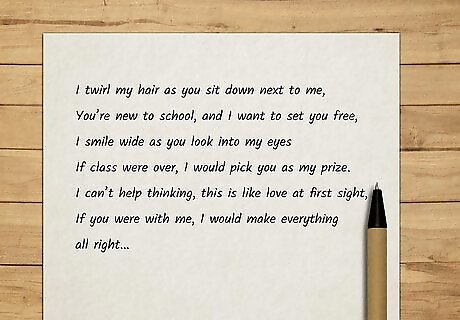

Find your favorite lines and build rhymes off of them. Say you're writing about school, and you have the line, "Pushing pencils for a teacher no smarter than me." Instead of trying to write the whole song at once, use this line to start building. All you need is one good line to get the ball rolling. What would you rather be doing than school ("I'd rather be picking apples and swinging from trees")? How do you know the teacher is no smarter than you ("My paper on quantum physics only got me a C")? Most song verses are only 4-6 lines long, so this is already halfway to a verse!

Develop a simple hook or chorus. The hook is the repeated part of the song. It should be simple and fun, and usually tells people what the song is about. A good strategy for a hook is to just write two good rhymes and then repeat them, helping them get stuck in the listener's mind: Choruses should be simple so that they are easy to remember. Hooks don't even have to rhyme, as seen in the famous Rolling Stones hook: "You can't always get what you want / But if you try sometimes you might find you what you need."

Cut away any excess words, lines, and ideas until only the best stuff remains. Songs are short and to the point, and the best songs don't waste a single syllable. When revising songs, think about: Action words. Don't rely on "is," "love," and other commonly used words that everyone has heard. Try to use unique, precise words to convey the song's emotion. Trimming. How can you re-write a line to make it shorter and more to the point? Where are the lyrics vague? Instead of saying, "we got in the car," say the type of car. Instead of talking about going to dinner, say what type of food you ate.

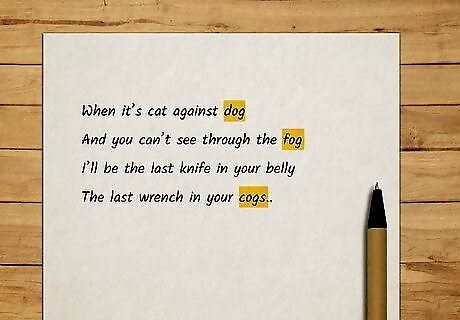

Explore different types of rhymes. There are a lot of ways to write a song, but almost all of them rhyme. The best practice for beginners is to understand the types of rhymes they have available and just work on simple, 2-4 line sections of rhyming lines. As you pull these together, a song will slowly be born: Simple Rhyme: This is simply rhyming the last syllables of two lines, like "I've just seen a face / I can't forget the time or place." Slant Rhyme: This is when the words don't technically rhyme, but they're sung in a way that makes them appear to rhyme. It is surprisingly common in all forms of songwriting. Examples include "Nose" and "go," or "orange" and "porridge." Multi-syllabic rhyme: This uses multiple words or syllables, all of which rhyme. Check Big Daddy Kane on "One Day," where he raps "Ain’t no need for wondering who’s the man/ Staying looking right always an exclusive brand."

Think of your song like a small story. Even songs about a feeling or political idea can learn from storytelling techniques. You want an arc, or some change or progression. For example, think about how many love songs start with how downhearted or low the singer is before the girl/guy showed up. You get a journey through the romance, which makes the lyrics interesting. If you're writing a full song, just think of each verse like a scene in a short movie. Since most songs have three verses, this simply means a beginning, middle, and end. Taylor Swift, Singer & Businesswoman Putting pen to paper can be cathartic. "I think songwriting is the ultimate form of being able to make anything that happens in your life productive."

Stick to one idea or theme per song. Even Bob Dylan, one of the most convoluted and complicated lyricists of all time, knew that a good song must be grounded in one good idea. Looking simply at Dylan's catalog, the songwriter shows that the best songs explore one idea deeply, not a ton of ideas briefly: "Blowin' in the Wind," which examines lots of issues, grounds itself with a simple question in the beginning of every verse -- how long can an injustice last before it must change? "Tombstone Blues," one of Dylan's more expansive and out-there songs, is about a worry about what written and remembered on our tombstones after we die.

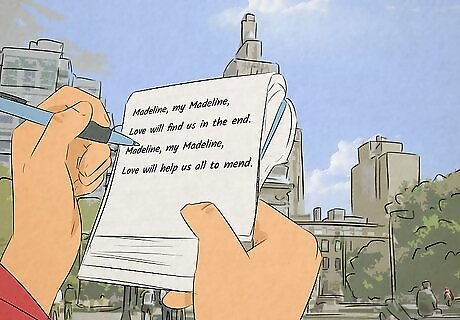

Keep a notebook for writing down catchy rhyming lines, even if they don't form a song. Over time, however, these small bits will provide the springboards for entire songs, mixing and matching to help get started on a tune. Keeping a notebook or a phone note on you is the best way to capture ideas whenever the come up. Prolific songwriter Paul Simon claims that all of his songs are composed of these loose pieces. As he finds some that match up, he slowly builds up lyrics to a song.

Writing Full Song Lyrics

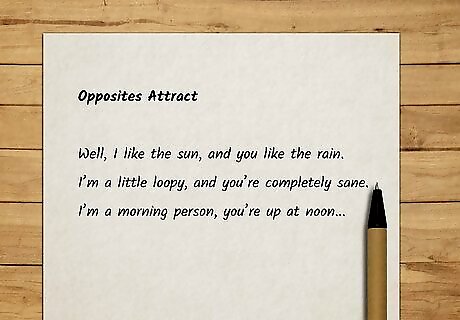

Use the title of the song to set the mood, theme, or most important idea. The title of the song could be the chorus, or it could be some other word/phrase you think sums everything up. The title is the audience's first clue as to what the song is about or means, so take your time thinking of it. That said, don't make a complicated title if you don't have to. Most songs use the chorus lines for a reason -- the chorus is already stating the main theme of the song.

Organize your lines into a rhyme scheme. A good way to think about this is a rhyme diagram, where each letter symbolizes a rhyme. So, in an ABAB rhyme scheme, the first line (A) rhymes with the third (A) and the second line (B) rhymes with the fourth (B). There is also AABB, where lines just rhyme back to back. There are hundreds of ways to structure your rhymes, so start playing with your lines until you like the sound. ABAB, or "alternating rhyme" is also common, and is easily written by splitting two long line into four ones. Really technical writers might try to rhyme 4-6 lines in a row. This could be an AAAA BBBB rhyme scheme, or even AAAA AAAA if you're feeling extra complicated. Some writers will try extending out a rhyme over multiple verses. Like an AAAB CCCB scheme. For an example, tune into "Tombstone Blues."

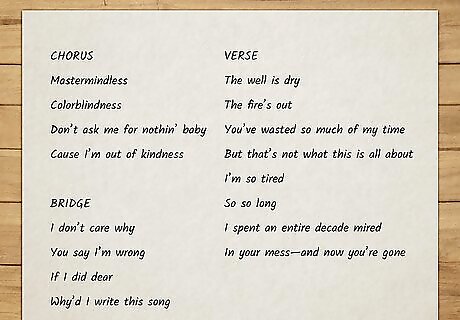

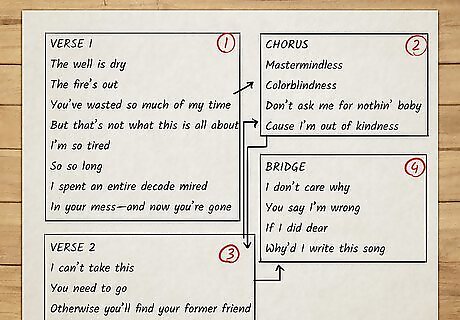

Know the lyrical parts of a songs. There are, in general, three main sections of a song, not including an intro or outro (which can, of course, have lyrics). These three sections are mixed and matched to form the final song: Choruses/Hooks are the repeated sections of the song, and the catchy area you hope everyone remembers the song by. They are usually short, and identically repeated. Verses are generally the longest, most unique sections, where you expand on the ideas of the song and make your point, tell your story, etc. Bridges, also called "Middle 8s," are sections with different instrumentals. They often transition between a chorus or verse, or provide one section of differing texture and sound. This can be an instrumental solo, or cue a change in the mood or theme of the lyrics.

Order your verses, choruses, and any bridge. Once you've got at least a chorus and a few verses written you can start thinking about how they alternate. You can even write a bridge to mix things up. The most typical song structure is intro/ verse / chorus / verse / chorus / bridge / chorus / outro, but there is nothing marrying you to this structure. Another popular trick is to use multiple bridges to get from each verse to each chorus-- something like verse / bridge / chorus / verse / bridge / chorus / etc. Bridges can also be instrumental breaks like guitar solos.

Hum, whistle, strum, or play around on a piano to find the lyric's melody. Writing your own lyrics is only half the battle -- you need to know how to sing them, too. Even if you're a rapper, you still need to think about "flow," or the pace and rhythm of your words. The best way to do this is to experiment, usually with an instrument of some sort like a piano or a guitar, but you can even whistle or hum until something sounds good as well. Paul McCartney of The Beatles famously found the melody to "Yesterday" by just repeating the words "Scrambled Eggs" until he found the notes. The lyrics were put in later.

Improving as a Songwriter

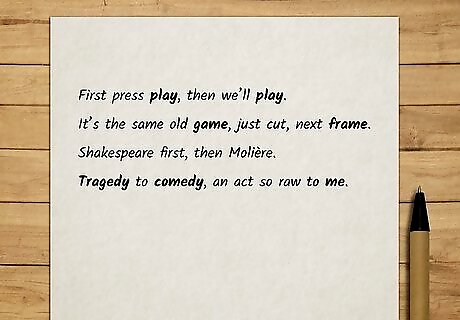

Play with internal rhyme to give your lyrics a more melodic, sing-song quality. Internal rhyme is when you have smaller rhymes hidden in the middle of lines. You still have your normal end-line rhymes, just with a bit more flavor in the middle. For an example, check out this MF Doom line off "Rhinestone Cowboy:" "Made of fine chrome alloy / find him on the grind he's a rhinestone cowboy." A good way to start with internal rhyme is to cut your lines in half, treating a rhyming couplet like 4 short lines instead of two longer ones. Internal rhyme doesn't have to be regular, like regular rhyme. Even one or two in a song can have a wonderful effect. You can even have internal rhyme in the same line, like another MF Doom line, "never will he boost loose Philly's with the bar code."

Rhyme lots of lines together for melodic, tight sections. Check out the Red Hot Chili Pepper's "Californication," which rhymes a majority of lines with the title word, "Californication." Because so many of the lines rhyme with this one, singer Anthony Kiedis doesn't even need to rhyme the 1st and 3rd lines of each verse with anything -- giving him "free" syllables in each verse. Another strategy is to rhyme the last line of each verse with the last line of every other verse. Check out "Simple Twist of Fate."

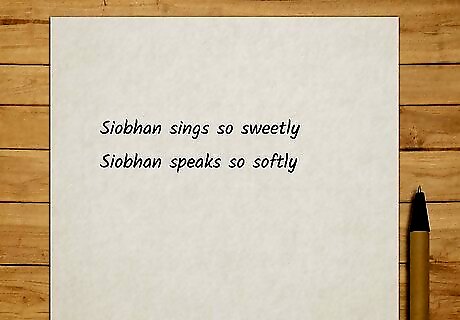

Use poetic tools to add musicality without rhyme. Lyrics are poems put to music, and there is a lot to learn from the thousand-year-old art form. The following tricks can be slid into any lines to put a professional, deeply satisfying sheen on your songs: Assonance is when you use the same vowel sound multiple times, such as "awesome apple" or "evidently envious." Alliteration is just like assonance, but with consonants. Examples include "slippery slope" and "washed out water polo women."

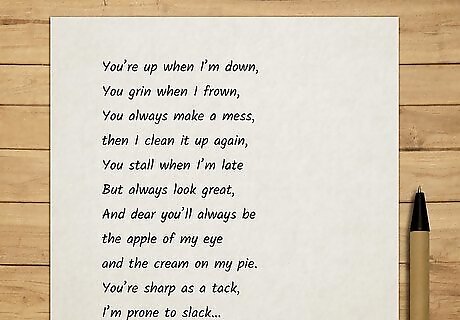

Write a few metaphors and similes. Not all songs need to have deeper meanings, and many shouldn't. Even worse, some songs try too hard to push deeper meaning and just end up confusing or meandering. That said, a well-placed metaphor can turn a song from a catchy tune to a powerful, personal, and impactful song: Metaphor is when one thing is implied to stand in for another, like the song "Firework" by Katy Perry. She doesn't literally mean that "you're a firework," she means that you contain a beautiful interior life waiting to explode into the world. Simile is a more direct metaphor using the word "like" or "as." "She was like a rose," for example, implies that she is beautiful, but may be dangerously thorny. Synecdoche is when a small part represents a bigger whole. For example, "the pen is mightier than the sword" actually means that "ideas are stronger than violence," not that pens literally beat up swords.

Try to rhyme uncommon or inventive words. The most impressive lyricists know that audiences have come to expect many of the rhymes in popular music -- "we/she/he/me," "love/dove," "go/so/low/blow." -- and they lose their power to pleasantly surprise us. The songwriters who stand the test of time continue to surprises us with longer and more intricate rhymes. From "Tombstone Blues:" "My advice is to not let the boys in" // "You will not die, it's not poison." Very few other people have rhymed "boys in" with "poison."

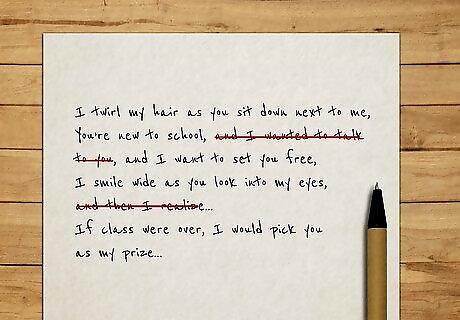

Rewrite, rewrite, rewrite. The best lyricists in the world know that a song rarely comes out perfectly in one go. Paul Simon even claims that it takes 50 sheets of paper, all with scribbled lyrics, for him to complete just one song. A good songwriter knows they must keep working on songs long after the first think of the idea. Keep the old copies of your drafts, that way you can always return to an old version if you want to try something new and it doesn't sound great. Use gigs and shows to test out new songs in lyrics. Where did they feel good and where was it awkward to sing through? What sections did people seem to like?

Ground your lyrics in real events, objects, and things. A song heavy on philosophy isn't a bad thing, but you need concrete images to help your audience visualize the ideas. Turning back to "Blowin' in the Wind," note how Dylan couches each big societal woe in a real image -- a mountain crumbling, a man walking, a lonely dove, etc. -- so that the song places a literal image in the audience's head. Details, images,and specifics will almost always go better than broad generalities.

Comments

0 comment