views

Washington: It seems that the root of all your weight problems lies in your gut, as scientists have identified a key microbe in the gut that helps collect more calories from food.

The discovery backs the idea that the type of microbes in our gut help to determine how much weight we gain, and that seeding the intestine with particular bugs could help fight obesity.

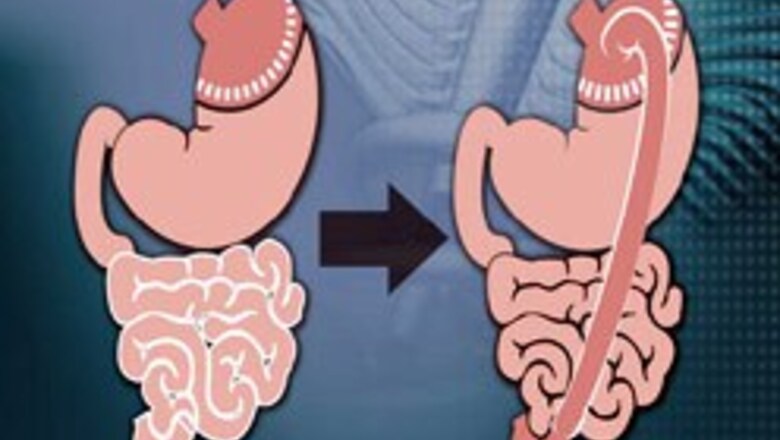

Our intestines are teeming with bacteria and other microorganisms that help to digest the food we eat.

But scientists are only just beginning to tease out what each microbe does amidst the swarming life in these dank, dark tubes.

Samuel Buck of Washington University in St Louis, Missouri, and his colleagues focused on one microbe called Methanobrevibacter smithii (M. smithii), which is effectively a waste-removal bug. It eats up the hydrogen and waste products released by other microbes, and converts them into the methane that escapes from our rear ends everyday.

"It's a minor component of the gut flora with a major impact," Buck says tactfully.

M. smithii may have a dirty job, but Buck and his colleagues have now shown that it is a vital one.

They found that by clearing waste products it helps other gut bacteria digest some of the fibrous components of food that we cannot, and turn them into material that our bodies can use.

Without these bugs, waste accumulates and blocks the activity of other gut bacteria.

The researchers found that mice with a hefty dose of M. smithii in their guts are fatter than those that don't have the bacteria.

The researchers took mice that had been grown in a sterile environment, with no microbes in their guts, and injected them with a very common strain of human intestinal bacteria, called Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron.

Some of the mice also received a dose of of M. smithii.

About 100 times more microorganisms took up residence in the colon of mice injected with both B. theta and M. smithii than in those injected with B. theta alone.

This suggests that the presence of waste-removing M. smithii was somehow helping other bacteria to thrive. "There's something cool going on," Buck says.

Comments

0 comment