views

New Delhi: On August 7, 1977, fish flew out of the river. That day, the day of the flood, the river began dying.

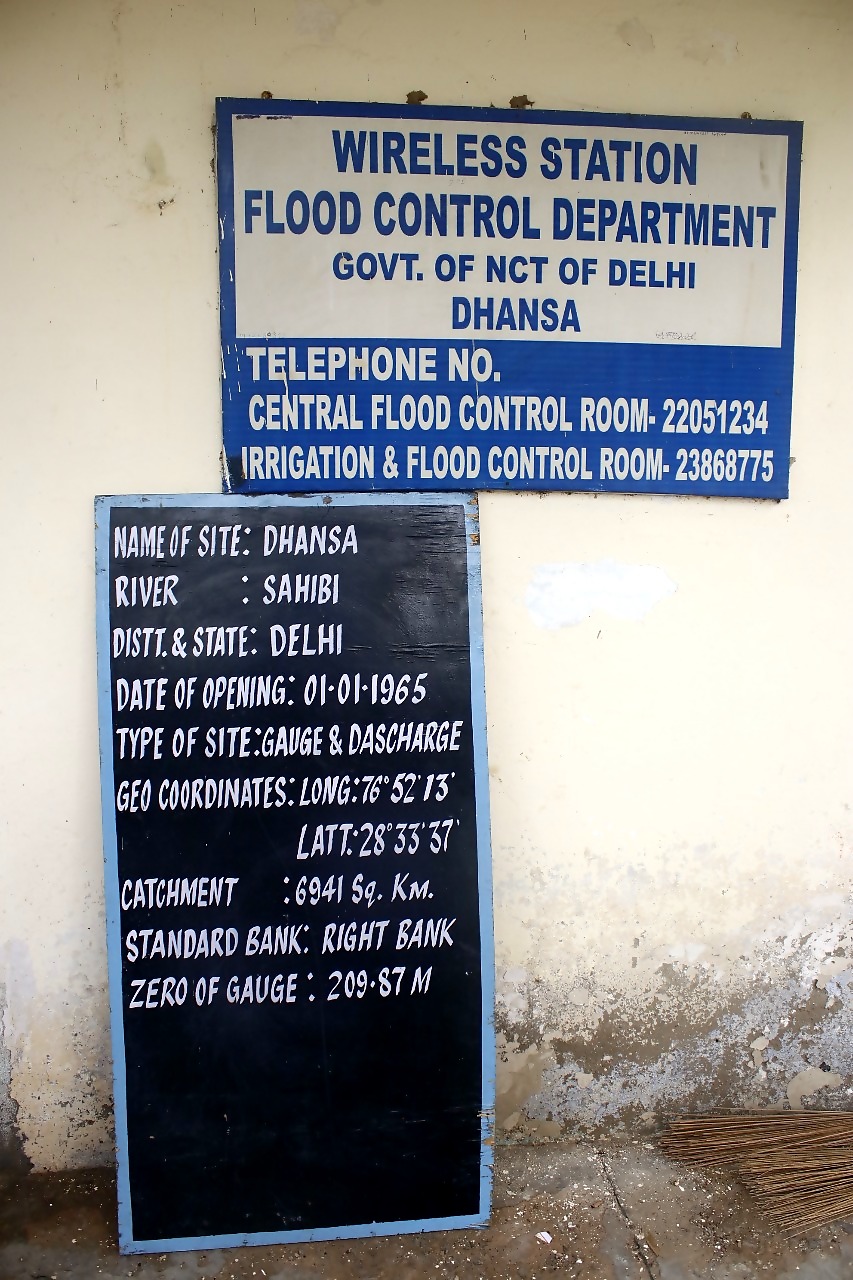

The Sahibi river, which as per an 1807 map of the Environs of Delhi was once connected to the Yamuna, is now ‘regulated’. It has become the 51-km Najafgarh drain that flows through nearly the entire breadth of the capital, carrying not just Delhi’s refuse but also its refusal to care about its water.

In 1977, water had risen above the Dhansa bund, with half a dozen breaches on the drain.

At least 72 villages and 33 urban colonies had been warned of imminent inundation. -The Army had been pressed into service, while Delhi Chief Executive Councillor Kidar Nath Sahni had said, “The magnitude of the situation has to be seen to be believed and even then it is difficult.”

His walkie-talkie sputtered urgently, while he explained that everything had changed after the flood. The government had decided to divert the river into Rajasthan, and three years later, the channel would be further widened. With little water, barring industrial effluents from Gurgaon, the water turned rancid and began killing the fields that the river had once sustained.

From the first point on Yamuna’s course where it begins to get polluted, to the lives of those who struggle for water while living alongside forgotten drains like the Barapullah, the question of Delhi’s water woes has no simple answers.

As a part of this series, News18 had previously investigated how unplanned development and seemingly unrelated, but interconnected decisions changed the capital’s relationship to water.

In this story, we explore how Delhi converted an old river into a sewer and polluted its waters. Thus, contaminating not just the other river, Yamuna, but also the rapidly depleting aquifers below with poisonous heavy metals that are deadly for human beings, linked to diseases ranging from skin cancer to damage to the kidneys. Worse, there were warnings and they were ignored.

At Najafgarh, none of this is news to Dayal Singh. Forty-two summers after the deluge, Sahibi is blue only on maps. He knows that what he now views, are the rotting remains of a long, lost memory.

How the River Was Lost to a Flood

For 80-year-old Jaage Ram, the stagnant brackish water, that flows upstream, presumably due to effluent discharge, isn’t the river he once knew. Clutching a hookah in his frail hands, Jaage Ram spoke of Sahibi with a fondness usually reserved for a long-lost relative. The river, he explained, wasn’t always like this —slime glistening over saline, undrinkable water. For centuries, it sustained life: water from the river was used for irrigation, it was sieved through a clean cloth and kept in earthen pots to stave off hot summers.

The signs of the past that Jaage Ram speaks about can now only be found in a long forgotten map in the Delhi government’s archives. The 1807 map, for instance, shows a cluster of 11 villages around the canal. Another map, a plan for the Najafgarh jheel and drain, traced from the drawings of the settlement office of Delhi in 1879, shows a total of 2,897 fields.

Forty-two years after the flood, in April 2019, more than 2,000 farmers from the same villages surrounding the drain wrote a letter to the state human rights commission asking to be compensated for losses suffered by them due to the polluted drain. This wasn’t without precedent. Scientists and experts have, time and again, flagged the dangers.

As early as 1986, a two-year study of the Yamuna in the Delhi found “very high bioaccumulation” of pesticides in life forms ranging from fishes to earthworms. In 2010, a study by the Indian Agricultural Research Institute warned that it was time to “devise policy guidelines for efficient management of both surface and groundwater” after it found Nitrate concentrations to be far higher than standards.

In 2013, another study found that “recharge through (the) drain water (had) led to influx of trace element/ heavy metals into the groundwater”.

This year, it wasn’t just the harvest that took a hit. Countless warnings unheeded, access to drinking water has also become an increasing challenge for those at Sarangpur. Although the Delhi Jal Board’s water tankers cater to these villages, Ram complains that it is never enough. “Farmers used the water from the drain for irrigation. But now, it is leading to a fall in both quantity and quality of the produce,” rued the 80-year-old.

Delhi transport minister and Aam Aadmi Party MLA from Najafgarh, Kailash Gahlot said that drinking water is being provided in all areas and the government is trying to plug the gaps.

“As far as farm issues are concerned, decentralised sewage treatment plants (STPs) are already coming up. Mostly, all these issues are already sub-judice, most of them in NGT at some stage or the other. If you travel from Chhawla village in Najafgarh to Bijwasan along the drain, there is a bundh in place in Delhi but not in Gurugram, Haryana. The water therefore just flows into agricultural land in this area,” he said.

He further explained that there is a serious violation of environment laws when it comes to untreated water flowing in Najafgarh from Gurugram via three drains.

The first flood on the Sahibi was in 1964. Its waters swelled up over its carrying capacity of 900 cusecs, damaging the bundh that had been constructed two years earlier. Soon after, as per records of the Irrigation & Flood Control Department, a crevice or “controlled cut was made” through the bundh. But this, in turn, would lead to further breaches that caused floods in 1967, 1975 and 1976. However, it was the flood of 1977 that would be the final nail in the coffin for the river.

An Indian Express report from August 7, 1977 said the Najafgarh drain was breached at a half a dozen places when the water levels rose by over 13 ft. “Consequently the entire Najafgarh jheel and vast area of Delhi came under submersion,” the Irrigation and Flood Control department notes.

Ram recalls that nearly “60-65 villages were inundated with water” and that water had risen to his waist. Soon after, the Centre formed a high-powered committee to devise a flood control plan, while coordinating with Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi. The Masani Barrage was planned at a cost of Rs 50 crore.

By then, the Haryana’s ecological landscape began reeling from the drastically expanding and intensifying agricultural activity spurred by the Green Revolution.

“The agricultural belt of Najafgarh was not traditionally a rice-growing region. In order to push the green revolution, crop patterns were changed. These high-yielding crops required three times more water and needed chemicals for growth. This completely changed the ecology in the area for the worse,” said Vandana Shiva, environmental activist and scholar.

She also highlighted that the diversion of seasonal rivers stopped the flow of freshwater and this stagnation happened.

Rameshwar Rass and Ramjas Swami in ‘Irrigation System, Cropping Patterns and Ecology: A study of Haryana in Second Half of 20th Century’ notes that “increased irrigation facilities, the transformation of cropping patterns, intensification of cultivation and use of HYVs (High Yield Varieties) and excessive use of fertilizer and pesticides” during this time led to problems like water-logging and rise in salinity.

“So, the increasing number of barrages and the increasing intensity of agriculture meant that all the water was being pulled out of the seasonal rivers like Sahibi,” Diwan Singh, convener of National Heritage First, added.

Killer Pollution and Ignored Warnings

The Sahibi, now forgotten, had turned into a sewer. The polluted waters of Delhi contaminated not just the vulnerable and increasingly stressed aquifers below, also began contributing 60 percent of the total pollution in the waters of the Yamuna.

As Gurgaon, now Gurugram, grew and gulped water, its mounting sewage found its way into the drain. Roughly 50 per cent of Gurugram’s sewage flows through drains and pipes, reaching the Najafgarh drain, found the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) in 2005.

Three drains — Leg I, Leg II and Badshapur drain, with an average discharge of a cumulative 549 MLD (million litres a day) — bring Gurugram’s sewage into the drains, as per an NGT report.

The Tribunal has, in fact, been hearing two separate cases in connection to the drain. Last September, a monitoring committee had been appointed for Delhi, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh with the sole objective of curbing this discharge into the Yamuna and in its report earlier last month, it found that a bad situation was made worse by the poor condition of the Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs).

Of the five STPs in Gurugram town, two are “operational but having functional problems”, two are “under upgradation” and one “under stabilization”, said the report, adding, “Thus, partially treated and untreated domestic effluent is being discharged to the Najafgarh drain via Badshahpur drain.”

For those living alongside the drain, the problem is one that permeates everything.

Many, like 52-year-old Nand Kishor, a washerman living in Dwarka’s dhobi ghat, had moved here 10 years ago because of accessibility to water.

“Now, there is a serious stench. The water is almost unusable. The wastewater from the nearby colonies pools up here,” he said.

Around 10 km away, the drain enters into Vikaspuri, falling under Delhi’s Patel Nagar. A swathe of flies envelope the drain and a local fruit vendor in the market has the thankless job of swatting them away from his wares. “It is a rotting, large stretch of garbage,” he complains. By the time the drain meets the Yamuna at Nehru Vihar, its water turns inky black.

The Delhi government’s solution, for the last 13 years, has been the same. An interceptor project, which envisions the laying of trunk sewers running parallel with a major drain to intercept wastewater from smaller sewers and then treating it. This, the government hopes will reduce the flow of untreated wastewater reaching the Yamuna. Last week, the NGT finally had enough and called for an independent audit by technical experts to verify the Delhi Jal Board’s claims that the Interceptor Sewer Project would actually be able to stick to its latest deadline – December 2019.

But that is only one half of the larger problem. In 2013, hydrogeologist and formerly a scientist with the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) Shashank Shekhar for eight years, pointed in a study that 31 of the 51 km of the drain before it reaches the Yamuna was “unlined”.

He warned, “The shallow groundwater along the Najafgarh drain” — in areas ranging from Najafgarh, to Dwarka to Nehru Vihar — was “contaminated in stretches” and the area “is not suitable for large scale groundwater development for drinking water purposes”. That the water was contaminated with heavy metals had been known, but he warned, “It is quite possible that along with seepage recharge from the drain, the heavy metal contaminates the groundwater as well.”

Arsenic, that the WHO notes can cause skin cancer, was found to exceed not just Indian standards in 3% of the samples. Cadmium, a heavy metal commonly used in batteries and electroplating, was found to exceed WHO standards in 69% of the sample and Indian standards in 3% of the samples. Cadmium has been linked to kidney damage and osteoporosis by the WHO.

A CGWB booklet on the South West District of Delhi in 2011 had listed the “high fluoride content at Najafgarh” under the “major groundwater problems and issues”. Fluoride in water can cause calcification of ligaments, pain in the joints and even “severe skeletal problems” warns the WHO.

Now at the Delhi University’s department of Geology, around 20-minute walk from the drains lined, but exceedingly polluted Model Town section, Shekhar explained, “What happens with the pollution load, which is moving along the drain and its subsidiary drain is that they contaminate the aquifer wherever there is an opportunity,” he says.

The ‘opportunity’ he refers to is the 31-km unlined stretched that begins at the Dhansa regulator and since the load increases, the groundwater only gets more contaminated downstream as the drain reaches closer to the Yamuna.

It isn’t just the decreasing groundwater levels, the surrounding aquifers have also been stricken by the increasing contamination load — a consequence of the development that has taken place in and around Dwarka. “You have in its catchment areas in Dwarka a lot of industries, domestic sewers…So what happens, this pollution load contaminates the aquifer wherever there is an opportunity,” Shashank explained.

In his office in Delhi University’s North Campus, Shashank takes a few minutes to scour through the clutter of books, reports and papers on India’s water resources. He pulls out a graph from the study he had done back in 2013, which assessed the groundwater quality in aquifers around the drain.

Cadmium and chromium are highest at Dwarka and then from Nihal Vihar all the way till Timarpur, which is right at the banks of the Yamuna, it says. “We wanted to red flag these things so that the government agency is always cautious from the beginning… but it took 19 years of continuously conversing on different forums for that to happen,” Shashank said.

The main problem, he summarised, is that an old river, once forced to near-death, was converted into a sewer, without considering the implications and then ignoring the many warnings.

“If any old river that is at a dying stage is conserved as a recharge structure it will solve a better purpose than a sewer drain. This is the main problem with the Najafgarh drain,” he said.

(This is part of the series that takes an expansive look at Delhi’s water systems and how they’ve been governed.)

Comments

0 comment