views

This year, Indian state governments, so far, have market loans (SDLs), borrowings amounting to Rs 1.93 lakh crore, which is 76 per cent higher than the corresponding period last year. This rise is already sitting on leveraged balance sheets of states. Especially, states like Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh had an accumulated outstanding debt of around Rs six lakh crore while Maharashtra had a debt of Rs five lakh crore. While the GST meeting today is about dispute resolution of existing outstanding dues, the bigger question that remains is how the states are planning their expenditure.

Will they be able to cross the river of debt safely? Every state in India is facing a liquidity crisis, the degree varies depending upon their management of planned expenditure. States’ borrowing has shot up in the last quarter and they have started reducing expenditure but it is not enough. State government investment is important and is the largest component driving the economy, it is much more than the private sector or Union government investment. Hence, if the states stop investing in capital expenditure due to the financial crisis they are facing the overall economy will further slow down.

The GST council in its October 5 meeting almost rejected the demand of 10 states for immediate payment of compensation arising out of GST implementation. However, the council approved an additional Rs 24,000 crore of IGST dues and Rs 20,000 crores of compensation to be released immediately. This may ease the liquidity crisis faced by the state governments but does not solve the problem. The problem is liquidity, debt management, and expense prioritization. There is a sea of expense, and a rising debt burden, due to the delay of compensation. Along with this, there is now a liquidity crisis too.

Every state government is facing an important dilemma. How to navigate the sea of expenses on a borrowed boat. A boat that is continuously being overloaded with more and more debt. The falling GST revenue from the Centre combined with falling tax collection by the states from housing and excise revenues is pushing towards a liquidity crisis.

The Union government deferment of compensation is like a hole in that unsteady boat. The GST Council estimates that the total shortfall in this fiscal year will be about Rs three lakh crore at a GDP growth rate of 10 percent that is disputable. Out of this, Rs 65,000 crore is expected to be generated through cess. The estimated deficit of Rs. 2.35 lakh crore this financial year has to be bridged through borrowing by states.

But even in states that have borrowed to meet the shortfall, the cost of debt is rising. Property transactions are down because of lockdown and lack of certainty in home buyers’ minds. Revenue receipts from stamp-paper sales on property transactions, one of the biggest sources of revenue, is now scarce. This loss of revenues means that deficit financing has to be done through only market borrowings.

The immediate challenge for some states is to keep paying the salaries, pension, and subsidies. There is an immediate liquidity crisis in several states — the finance departments in states are delaying payments of subsidies or release of payment even under MNREGA.

This is affecting the implementation of state-level schemes, employment of temporary employees, and in the mid-term will slow down their economy, further creating a vicious downward spiral. If states do not manage their priorities of spending well, a debt trap can also happen.

The Union government was generous in the April-May period, transferring double the gross amount of collection under GST to states as their share of central taxes, but this liquidity is no longer available. The amount of transfer has been falling since June 2020, when it was down by 9%, almost Rs 4,000 crores, as compared to April-May. From August, the states have got a monthly average amount of Rs 42,000 crore, 9-10% down from earlier periods, as per RBI figures.

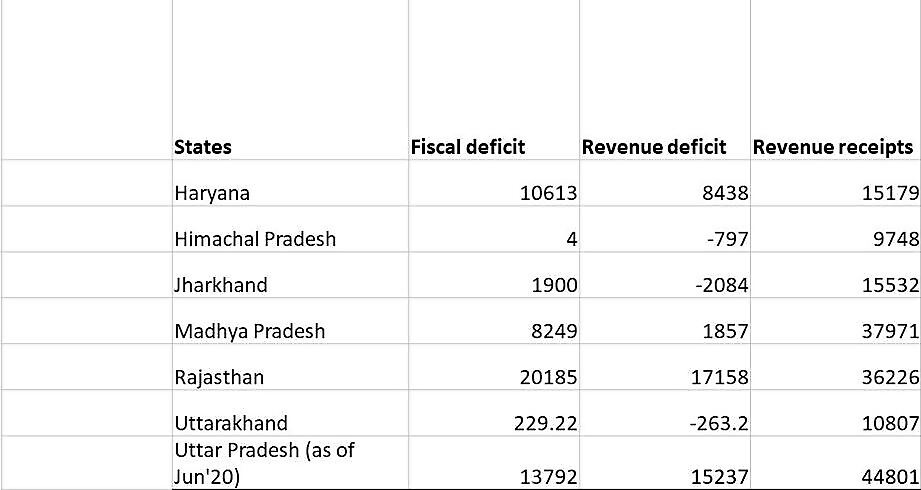

States like Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Maharashtra are facing a decline of over 30% in their GST revenues during April and August 2020, according to Minister of State for Finance Anurag Thakur. This sharp drop in GST revenues automatically means that the Union government will share less.

The states have reduced expenses, beginning with temporary staff. UP is set to overhaul the recruitment policy for all its Class B and C employees. Several of the Class C employees are temporary contract employees, till such time a new policy does not come out, there is unlikely to be any recruitment in these segments. Hence, there is no extra expenditure on salaries or allowance.

Almost 18 states have reduced their expenditure on salary and pension by over 10 percent and on subsidies by almost 40 percent. But expenditure on public health/administrative because of Covid-19 prevention or management measures have pushed ‘other expenditure’ by 40.1 percent.

Borrowing more debt on a highly leveraged or burdened balance sheet means that, for one, the cost of borrowing keeps rising and, secondly, a large part of the expenditure goes towards servicing debt. This leads to a debt trap, something that can happen in Punjab. The state has to go for more market borrowings at least to meet some committed expenditure of Rs 58,981 crore for 2020-21 (67% of the state’s revenue receipts).

Earlier, Punjab was allowed a net market borrowing of Rs. 9,098 crore in the period between April and December, but it quickly exhausted this borrowing limit and asked the central government to enhance the limit. States’ borrowing costs may spike, as in the first bond auction of the current financial year in April, Kerala paid the highest borrowing rate of 8.96 percent compared to fixed interest deposits of banks which is between 3.5% – 7 %.

Take the largest state Uttar Pradesh, in the April-June 2020 period, the state has notched up revenues receipts of Rs 44,801 crores but its expenditure shot up to more than Rs 58,500 crore. That means it has borrowed between Rs 10,000 to Rs 14,000 crores to fill the deficit. The state will have to continue borrowing for the next six months, but coronavirus is not going away and the economy will not revive soon. Farmers, migrant workers, and other sections of the society will need the state’s support.

How the state plans its expenditure during this period will affect a large section of the population. We cannot stop subsidies. Investment in rural and urban projects by the state has to continue as it is a source of employment and is necessary.

Everybody will have to borrow, so the crucial question is whether the states will spend the borrowed amount to boost the flagging economy or maintain the status quo. Whether the states will spend, fund new projects that will drive the economic growth or curtail all capital expenditure and just do nothing but debt management. When faced by an unexpected crisis, systems freeze, it takes able navigation to steer the boat in such times.

K Yatish Rajawat runs a public policy think tank in Delhi. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment