views

As India comes around to celebrate 25 years of the internet, we stand at a crucial juncture of connectivity for the entire country. For the already existing set of internet users, the target is to move on to 5G in 2021, and get super fast fixed line fiber broadband connectivity at homes. Further to the chase for ubiquitous internet connectivity in metro cities is the availability of public Wi-Fi hotspots – an area in which India still lags far behind developed nations. The key growth factor, though, is no longer coming from the major metropolitan cities that have so far fuelled the growth in internet services, mobile devices and connectivity. The ‘next billion’, as has been heavily billed, is set to come from the rural circles, with a completely unique set of needs and demands.

Growth in internet users

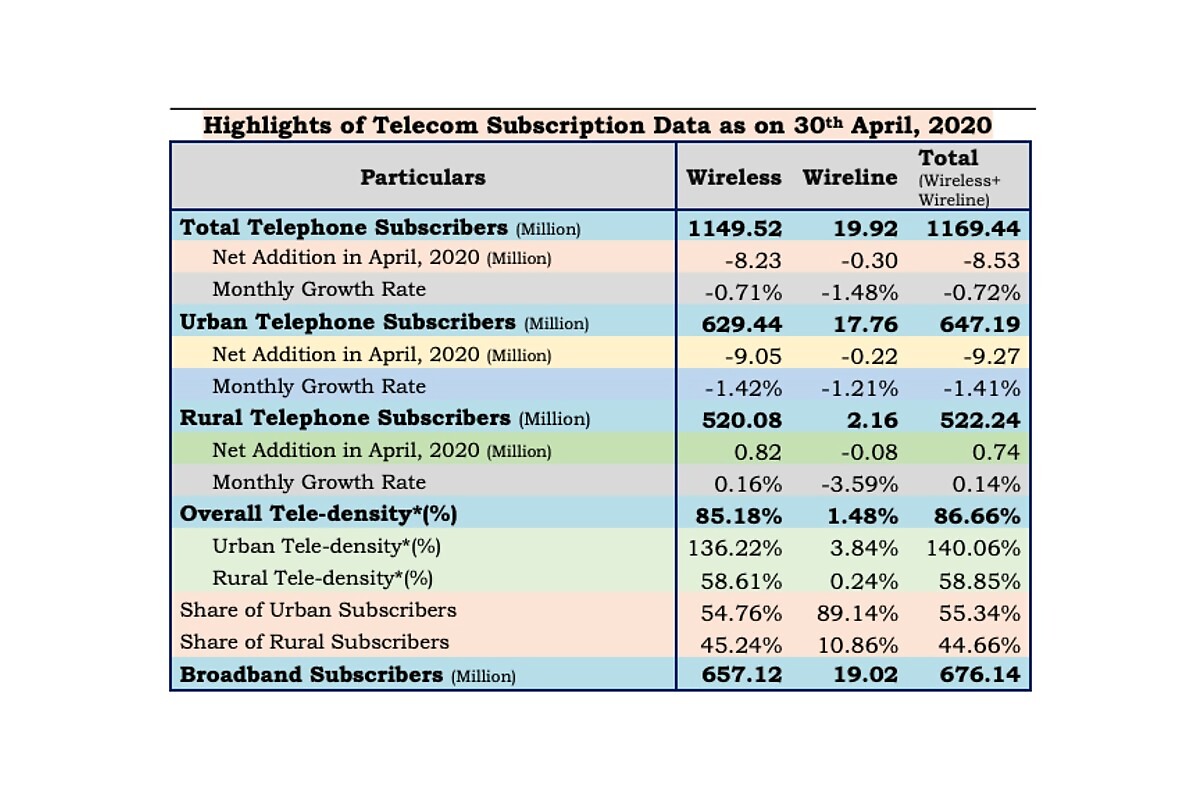

India has over one billion mobile phone users in the country – the most recent telecom subscriber report from the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) states that India has 1.15 billion mobile phone users in the country, of which 520.1 million users come from the rural circles. In urban circles, the rate of growth of new mobile users is far slower than that in rural circles – collating TRAI data between April 2016 and May 2020 reveals that while mobile phone subscribers in rural circles grew at 15.86 percent, the growth rate in urban circles was 7.74 percent. Metros, hence, grew at less than half the pace of Tier II cities and beyond, when it comes to new mobile phone connections.

While the advent of 5G may cause a momentary spurt of growth in the metro circles, the dominant pace of growth is expected to remain in the rural circles. At the moment, TRAI data states that 45.24 percent of all of India’s mobile internet users are from rural circles – up by about 2 percent in the past four years, since the advent of Reliance Jio. These numbers tell the precursor to the story that we expect to see in India in the next five years and beyond, and is key to understanding why the world’s biggest technology companies are interested in ‘the next billion’.

Rise of the vernacular internet

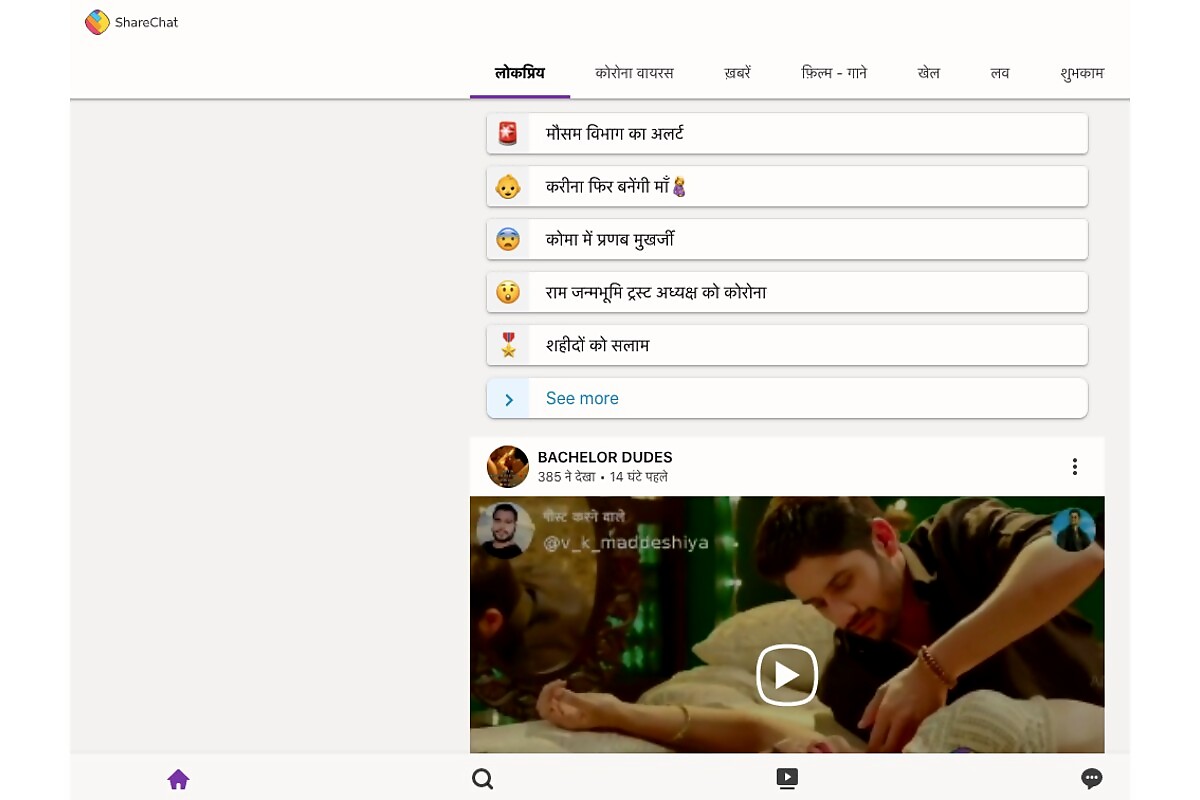

The influx of new internet users coming in from the rural circles have very different needs from the internet. A clear evidence of this is found the moment one looks at any of the latest social media startups that have come up in India over the past few years. For instance, ShareChat offers its social media platform in 15 vernacular Indian languages. Even on the smaller end of the scale, the ‘Indian Twitter’ app Koo, which recently won the second prize at the Indian government’s Aatmanirbhar App Challenge, has four vernacular languages already, with seven more set to come soon.

It is this language aspect that may hold key to onboarding first time internet users. Koo’s founder, Mayank Bidawatka, told News18 in an interview, “If you look at Twitter, over 300 million posts are published on Twitter every day. Out of this, about 75,000 are made in vernacular Indian languages. This shows an interesting statistic – users are interested in joining global social media platforms to connect with celebrities and personalities, but may feel inhibited due to their lack of expertise in the English language. Given that only about 10 percent of our country speaks English, this leaves a massive gap in the frame of the internet to be filled.”

Bidawatka’s theory gives a good idea of how the Indian internet industry is poised right now. Take, for instance, the now-banned viral social media app that set all of this in motion – TikTok. The service offered a democratised platform to everyone, urging people to create more content in their own languages. The content created could be anything – from hook steps of popular Bollywood numbers to quick food preparations and even reviews of gadgets. To round it off, TikTok’s audience was not the generations-old internet users from metro cities – instead, most were either new or first time internet users, for whom relatability to content played a greater role than just the content itself.

Making things available in local languages seems to be key to be getting India’s ‘un-digitised’ population on to the internet, and a large chunk of the spotlight is on how Indian startups make globally accepted and established internet models work for vernacular languages. Mayank Bhangadia, CEO and co-founder of Roposo, one of India’s largest local social media services right now, told News18 in a prior interview that the way content needs to be curated and presented to first-time and local language internet users is different from the globally established approach of long-time, English-first internet users that make up most of urban India.

As he said, “We have a full-stack proprietary technology model, which uses our own machine learning expertise to make our services better. We use it to curate the content feeds and also keep a close eye on quality control, in order to make sure that the platform remains family friendly. My own mother uses the Roposo app, and I personally would not want any kind of content on the platform that would make her uncomfortable.”

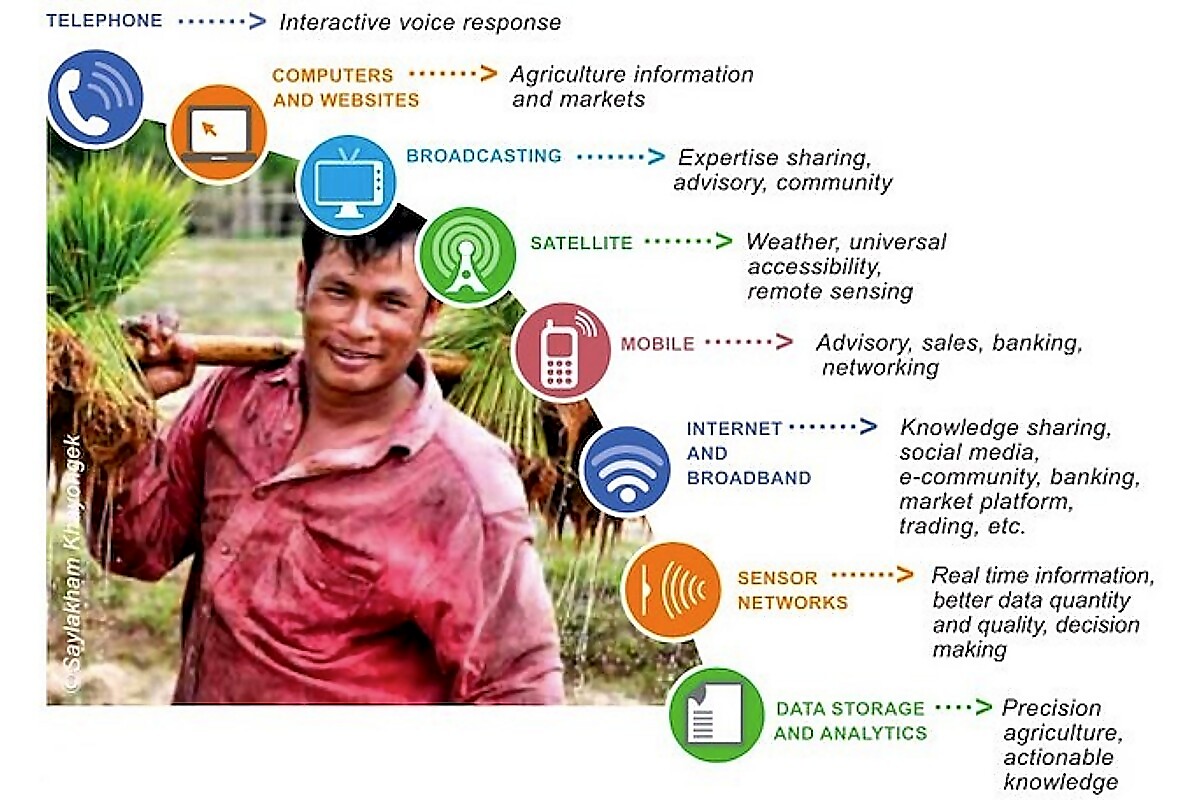

Digitising services

Alongside offering entertainment and networking platforms in local Indian languages, the key to expanding the internet to rural India lies in offering use cases that also fall into the more serious folds. These include digitising banking and financial services, offering e-learning and remote education, healthcare and software-based agricultural assistance, promoted by the government. It is this that IDC’s research director for mobile devices, Navkendar Singh, stated to News18 is a key factor that can contribute heavily to India’s expanding internet user base.

As Singh said, “The government needs to provide use cases for people in Tier II cities and beyond, for which they will see that investing in a smartphone is clearly worth their money. Internet is still deemed as a luxury for most of India’s rural working class, which is why they still prefer using a durable feature phone over smartphones. Unless use cases such as digitised utilities are brought forth, this class is not likely to switch to internet-enabled smartphones because the benefits are not tuned for them.” Singh further added that the growth in these sectors have so far largely been fuelled by services like TikTok and virally popular mobile game, PUBG.

The Indian government, on this note, has been partnering with companies such as Google and Jio Platforms to project technology-assisted utility services – tuned primarily for rural India. After 25 years of expanding in the metropolitan space, the internet in India looks set to take a new direction. It will be more vernacular and more localised, for which new technology stacks such as machine learning and neural network models can potentially set new precedents that other non-English languages around the world can follow.

Editor’s note: This article is part of News18’s 25 Years of Internet in India series, where we capture how the state of mobile services, home broadband, internet services and content have evolved, particularly in the past few years. We try to understand what the internet means for us, be it for the new reality of work from home, for entertainment of the habit of ‘binge watching’, music streaming, online gaming and more.

Comments

0 comment