views

Before he beheaded his 14-year-old daughter with a farming sickle, Reza Ashrafi called a lawyer.

His daughter, Romina, he said, was going to dishonor the family by running off with her 29-year-old boyfriend. What kind of punishment, he asked the lawyer, would he get for killing her?

The lawyer assured him that as the girl’s guardian he would not face capital punishment but at most 3 to 10 years in jail, Ashrafi’s relatives told an Iranian newspaper.

Three weeks later, Ashrafi, a 37-year-old farmer, marched into the bedroom where the girl was sleeping and decapitated her.

The so-called honor killing last month, in a small village in the rolling green hills of northern Iran, has shaken the country and set off a nationwide debate over the rights of women and children and the failure of the country’s social, religious and legal systems to protect them.

It has also prompted a me-too moment on social media of women pouring out their own stories of abuse at the hands of male relatives in hopes of shedding light on a problem that is usually kept quiet.

Minoo, a 49-year-old mother of two in Tehran, said her husband had beaten their 17-year-old daughter when he spotted her with a male friend in the street.

Hanieh Rajabi, a Ph.D. student in philosophy, tweeted that her father had lashed her with a belt and kept her out of school for a week because she had walked home from class to buy ice cream instead of taking the school bus.

Others shared stories of rape, physical and emotional abuse and running away from home in search of safety.

“There are thousands of Rominas who have no protection in this country,” tweeted Kimia Abodlahzadeh.

In many ways, women in Iran are better off than those in many other Middle Eastern countries.

Iranian women work as lawyers, doctors, pilots, film directors and truck drivers. They hold 60% of university seats and constitute 50% of the workforce. They can run for office, and they hold seats in the Parliament and Cabinet.

But there are restrictions. Women must cover their hair, arms and curves in public, and they need the permission of a male relative to leave the country, ask for a divorce or work outside the home.

Honor killings are thought to be rare but that may be because they are usually hushed up.

A 2019 report by a research center affiliated with Iran’s armed forces found that nearly 30% of all murder cases in Iran were honor killings of women and girls. The number is unknown, however, as Iran does not publicly release crime statistics.

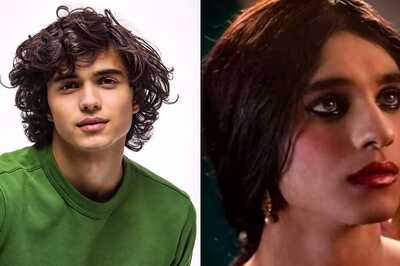

Horror over the killing of Romina Ashrafi, a round-faced high school student with a bright smile, was nearly universal, condemned by liberals and conservatives alike. Her father is currently in jail.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, called for “harsh punishment” for any man who abuses women in what appeared to be a reference to Romina’s case.

But the question of what to do about it broke along familiar lines.

“Everyone is infuriated and shocked because it’s a reminder that these laws are abnormal, these laws need to change,” said Shadi Sadr, a prominent women’s rights lawyer living in exile in London. “These laws were not meant for a woman or a child to be killed.”

Conservatives defended the existing laws and blamed Romina for promiscuity and disobeying religious and cultural strictures.

“The laws for violence against women are enough,” Mousa Ghazanfarabadi, a conservative cleric and lawmaker, told local media. “We cannot execute Romina’s father because it’s against Islamic law.”

President Hassan Rouhani asked Parliament late last month to fast-track legislation to protect women. The bill, which has been pending in Parliament for eight years, would criminalize emotional, sexual and physical abuse and impose jail time for violators.

A separate bill that would criminalize the abuse and abandonment of children has stalled for 11 years.

Domestic violence is thought to be widespread, and the chief of Iran’s family protection agency said in November that it had increased by at least 20% over the previous year, the IRNA official news agency reported.

The agency’s chief of psychotherapy said in April that reports of domestic violence had tripled during the coronavirus lockdown, and its hotline was receiving 4,000 calls a day.

Some women’s rights advocates see the current bill as an important step, but it is unclear whether the new conservative Parliament — elected in February after the majority of critics and reformers were disqualified — will pass it. Conservatives dismiss any effort to change the law as succumbing to Western feminism.

But even if the bills passed, they would not change the punishment for a father killing his child.

Murder in Iran is subject to the death penalty under the Shariah mandate of “an eye for an eye.” But the penal code, based on Islamic law, exempts a guardian from capital punishment for killing his child. A child’s father and paternal grandfather are considered legal guardians.

However, a mother who kills her child would face execution.

Under the Islamic patriarchy that has governed Iran for the past 40 years, changing Shariah is not an option. But some Islamic legal scholars and activists argue that the guardianship exception is based on tradition and interpretations, and is not found in the words of the Quran or sacred texts.

“How is it possible that a father kills and he is not held accountable and he does not face capital punishment?” Faezeh Hashemi, a prominent women’s rights activist and former lawmaker, told local media. “If we want to approach this issue with logic, wisdom and justice, the father needs to face retaliation punishment multiple times over.”

She said that passing the measure without changing the punishment amounted to window dressing and would offer no meaningful protection for women and children.

Other critics of the current law oppose capital punishment — a minority view on a penalty prescribed by the Quran — but argue that, regardless, a father should not receive a lighter sentence for the murder of a child.

Romina’s father had threatened her many times before he killed her.

The two had frequently argued.

When he discovered that she had a boyfriend, he flew into a rage, according to her mother, Rana Dashti, and other relatives. The details of Romina’s story were pieced together based on accounts provided to Iranian media by her family members, her boyfriend, his family and security officials.

The boyfriend, a farmer’s son who rode a motorcycle and sported a buzz cut and a tattoo, said he had been courting Romina since she was 12 and had proposed marriage. Iran has no law prohibiting an adult from having a romantic relationship with a child, and girls can marry with their father’s permission at age 13.

Ashrafi rejected the proposal not because of the age difference, Dashti said, but because he didn’t like the man’s family.

He confiscated Romina’s phone, kept her at home and began to threaten and terrorize her, Dashti told an Iranian magazine. One evening he came home with rat poison and rope, she said, encouraging Romina to commit suicide so he wouldn’t have to kill her.

Romina ran away, leaving a note.

“Baba you wanted to kill me,” it said, addressing her father. “If anyone asks you where Romina is, tell them I am dead.”

The struggle for women’s rights has a long history in Iran but has suffered setbacks since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The women’s movement was finally dismantled as an organized effort in 2009, criminalized on grounds that it threatened national security.

Today its most prominent faces, including the Nobel Peace laureate Shirin Ebadi and the feminist lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, are either in exile or in jail. Even Hashemi, whose father was president and a founding father of the revolution, was jailed.

“Women’s rights are politicized and criminalized making it very hard to channel this outrage on the ground into tangible action,” said Sussan Tahmasebi a women’s rights activist based in Tehran and Washington.

The advocates said they held little hope of changing the laws and culture that led to Romina’s killing.

Three days after she ran away, Ashrafi discovered her hideout and called the police, accusing the boyfriend of kidnapping. An investigator from the prosecutor’s office dismissed the kidnapping charge after Romina said she went with him voluntarily.

Romina pleaded not to be sent home with her father, telling the investigator of his threats on her life. But Ashrafi assured him of her safety and she was released to her father’s care.

By the next night she was dead.

After her case made headlines across the country, the prosecutor said that the investigation and trial will be expedited and that he will seek the maximum 10-year sentence for Ashraf.

In Romina’s village of Lamir, population 600, her school girlfriends still trek up the hill to the cemetery on most days. They lay yellow and purple wildflowers on her grave, and whisper a prayer that this will not be their fate.

Farnaz [email protected] The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment