views

Deciding to Conduct a Property Survey

Determine if you need to survey the land. The primary purpose of conducting a property survey is to prevent disputes about property lines. A neighbor's fence or buildings could be on your property, or vice versa, without your knowing about it. Surveys are often performed prior to the sale of a property, the beginning of construction on a building or fence, or when a property is being subdivided for sale. In essence, a property survey gives you the ability to know exactly where your property legally ends and the adjacent property begins. Only professionally-done property surveys are legally-binding.

Understand that existing boundaries may not be accurate. In many cases, and especially for rural properties, it may be the case that existing boundaries are not the real, legal boundaries of a property. You and your neighbor may have a fence or a natural boundary, like a ditch or creek, dividing your land. However, your deed may specify another line that must be used when determining the actual boundaries of properties.

Decide to survey the land yourself. Land surveying is a relatively difficult and time-consuming task, so expect to pay between $350 and $500, if not more, if you choose to have your land professionally surveyed. If you don't want to pay for this, you can survey the land yourself. However, keep in mind that doing so will not provide you with the same benefits of a professional survey. An amateur survey cannot be used in court, as part of bank-required information in a property sale, or as a way to move existing property markers to make them more accurate. An amateur survey can be used to get an educated approximation of your boundary line and may help you in property disputes of a non-legal nature (like your neighbor claiming that you're building a fence on his land). Professional surveyors can also provide you with information that would have a hard time getting on your own, such as gaps or overlaps with neighboring properties; easements; right-of-ways; your ownership of water features; relationships with the neighboring property (overhangs, encroachments, etc.); public infrastructure or utility rights; access points; and zoning issues.

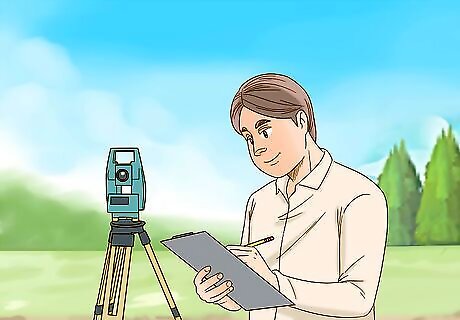

Hire a professional if you need one. Performing a property survey by yourself can be a more cost-effective way to go, but can potentially get you in trouble. If you're off by even a small margin and build something on a neighboring property, your neighbor can take you to court, which could end up costing you thousands. Consider the costs of making a mistake before deciding not to spend a couple of hundred dollars to have your land professionally surveyed. If you do hire a professional, make sure that they are licensed, insured, and have years of experience. Choose a licensed professional who specializes in property surveys, rather than a general contractor or handyman who sometimes does surveys on the side.

Planning Your Survey

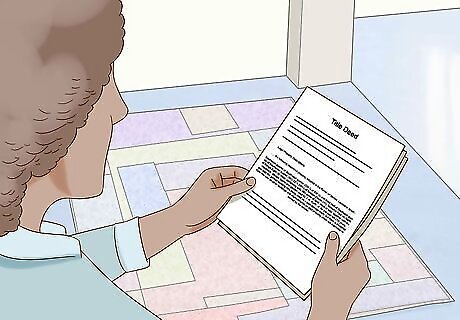

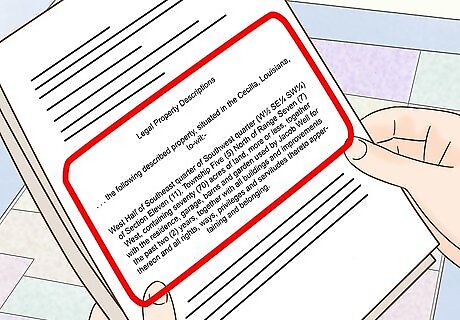

Acquire property documents. In order to determine where your legal boundaries are located, you will need at least one legal document describing your land. The deed to the land should have a section called "legal description" that describes the boundaries and the relationships between them. Another useful document is the surveyor's map of your land, also called a plat. Unlike your deed, the plat will show an actual map of the borders of your property and surrounding areas. Locating a plat for your land may be difficult or impossible. Sometimes they are included with the deed. Other times they may be present in your city or county's records. Check with your town or county hall to check if these records exist there. If you can't locate a plat, try locating those for surrounding properties. This can help you identify shared boundaries. A previous survey map can be unreliable, especially if it is very old. Keep in mind also that not all land has been surveyed.

Read and understand your property documents. The plat should be fairly easy to understand, as it shows the location of boundary lines and markers, and sometimes has other helpful information like coordinates or triangulation information. However, the legal description on the deed will be written in more confusing language and will use one of two systems for describing boundary lines: metes and bounds or the public land survey system (PLSS). Metes and bounds is a system that uses a bearing (or direction) and length (or distance) between points to describe the property. Bearings are described using a specific notation that converts compass azimuth (the degree markings on a compass) to bearing notation. This means adding a number (0 for NE, 90 for SE, 180 for SW, or 270 for NW) to the listed measurement to find the matching compass azimuth. For example, the description might list a starting point, then a next marker 200 feet to S50W from that point. This means that the next marker is 200 feet away and roughly to the southwest. S50W would be 230 degrees (50 +180) using the azimuth system (or almost exactly due southwest). Alternately, your land may be described by the original boundaries of the PLSS. This nearly 200-year old system split up land into 640-acre sections. It then split those sections into quarters, and those quarters into further quarters, and so on. Sections are numbered and then parts of those sections are described with fractions. For example, the NW 1/4 of the NW 1/4 of Section 4 would be the top, left-most 1/16th of Section 4.

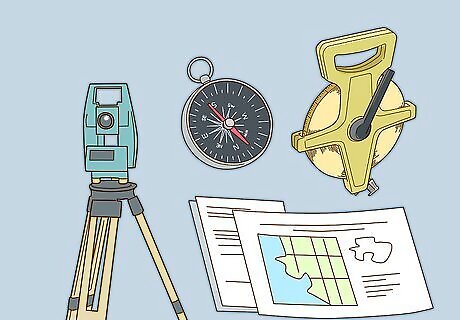

Gather your tools. You will need a method of ensuring that you are correctly following the heading towards the next marker and effectively measuring your progress. Most surveyors choose to use a compass and a very long tape measure for this purpose. You should also make sure to bring your maps and documents with you. Finally, bring a method of marking your property markers, such as brightly-colored flags or posts.

Locate a known corner. To start, you'll need a starting point. Legal descriptions usually specify a starting point to measure from, which can be anything. For example, it may say "50 feet SW of the road" or could start at a tree or rock feature. This point can be located on your property by searching the described location for a marker. Alternately, you can use the PLSS coordinates and maps to locate a starting corner. Google Maps and USGS topography maps are both free, online sources for maps that may help you locate a starting corner. Through these services, you can obtain a virtual copy of an aerial map for free. You may have to zoom in or out to distinguish boundary lines. The known corner may also be a neighbor's marker or road intersection. However, don't count on using markets like trees, fences, or rocks, as they may have been moved over the years.

Conducting the Property Survey

Start at the known corner. Grab your supplies and copies of your maps and head out to the property. Search the corner you discovered through your research for an existing property marker. If there isn't an existing marker, mark the corner yourself to the best of your ability with the information that you have. When locating survey monuments, be sure to be skeptical of whether or not the objects you find are actual monuments or just junk on your land. Unless they match up perfectly with your map or deed's description, they may not be what you are looking for. If you are unsure about the location or existence of such a monument, hire a professional surveyor.

Use your compass to identify the location of the next corner. Start at your corner and move your compass to find the bearing to the next marker. Plant your tape measure at the first corner and start walking, maintaining your compass heading. It may help to identify a landmark in that direction first, so that you know that you are staying on course. When measuring distance, know that the described distance is not in relation the topography of the land. That is, the distance is the horizontal distance only, not over obstruction or hills. Determining this actual distance may require you to find a way to keep your tape measure exactly level while measuring. If you cannot pass a certain area directly, move exactly perpendicular to your bearing until you can pass the obstruction, move forward towards the marker, then move back on course when you can by moving perpendicularly in the opposite direction.

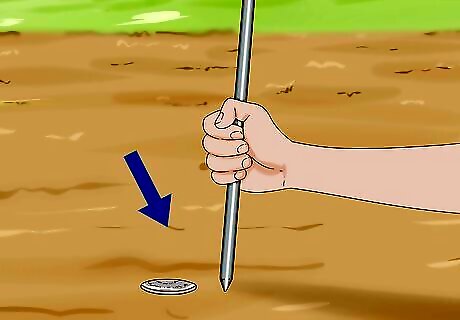

Mark the corner when you've reached it. When you think you've reached the next corner, search for the described marker. If you can't find it, it may be buried or missing. Try using a metal detector to locate if it is supposed to be a metal rod or spike. You can also use your compass as a metal detector by holding it very close to the ground near where you think a metal marker might be. When it points downward towards the ground and spins, you've located something metallic underground, which might be your marker. Markers can be anything. Modern markers are metal rods or poles, but old markets can be glass shards, etched rocks, wooden stakes, piles of charcoal, or anything else. Some markers may be impossible to locate accurately. Try locating the next corner if you can't find one. Locating the two neighboring corners can help you identify a missing one.

Repeat for the other corners. Mark the corner you've just found. Approximate it if you didn't find an existing marker. Then, repeat for the other corners of the property, making sure to mark each corner along the way. You may also choose the mark the property line regularly as you go. This can help you retrace your path at a later date if needed. After this process, you will hopefully arrive back at your starting point with a completely marked plot of land behind you. If not, you'll have to retrace your steps to identify what went wrong.

Comments

0 comment