views

Designing the Armor

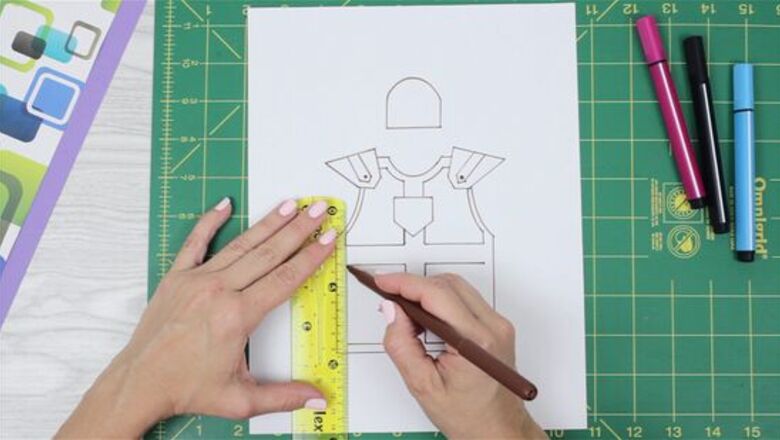

Sketch the armor design. Focus on the basic shapes (their size, and connections for adjoining pieces) rather than the color or detail, which can be dealt with later. Decide where and how individual pieces will overlap so that they can be connected and flexible. Simplify the structure where possible to avoid juggling lots of pieces and having to connect them in too many places (which will weaken it). You can also look online for ready-made patterns for armor, some of which you will even be able to print out. Here is a list of some common pieces of armor you will likely want to sketch: Helmet Breastplate Pauldrons or shoulder pieces Shield Gorget or neck protector. Arm pieces such as rerebrace, vambraces, and gauntlets. Leg pieces such as cuisses, poleyn, and greaves.

Take measurements. Measure the head size, height, waist size, arm and leg length, and any other needed measurements for the person that will be wearing the armor. These measurements will help determine the necessary dimensions that you will need to make the helmet, breastplate, shoulder armor, or any other miscellaneous coverings. Though these won’t be your primary means of sizing the armor, they will be useful to reference whenever you’re making a cut, connection, or alteration that you can’t accurately test.

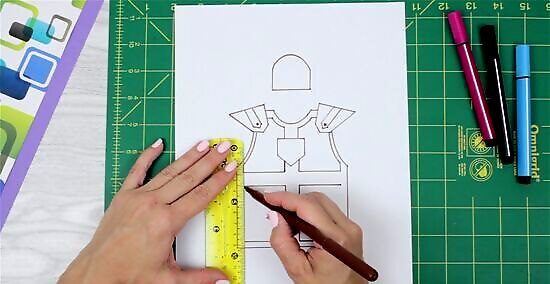

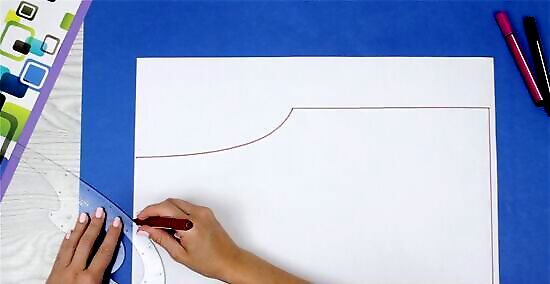

Transfer your measurements to an armor template (pattern). The fastest way to do this is to have a friend hold pieces of flexible, sturdy paper (such as poster board) against you and draw each piece of the design individually, creating a rough outline that you could then modify as necessary. A more accurate method would be to make a form (or a mannequin) to build the paper template around.

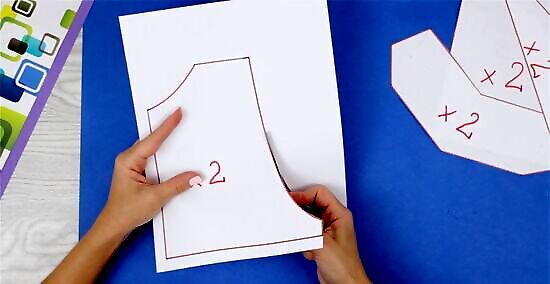

Finalize the template. Make sure all the pieces have been accounted for and adjust their sizes or proportions as necessary. Whenever you have matching pieces (e.g.: two shin plates, gauntlets, etc.), choose the nicer version and scrap the other one; that way, you can use the nice one as the pattern for the other to keep your armor symmetrical. When you’re happy with your pieces, clean up and smooth out the lines, label both your original sketch and the corresponding pieces (making note of any that will be duplicated), and cut all the shapes.

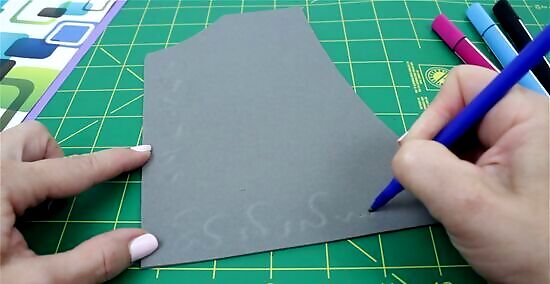

Transfer the template to craft foam. Trace each piece to the craft foam with a ball-point pen (which will glide smoothly over the material without snagging or tearing). Making duplicates of pieces where necessary. Label the undersides and then cut the shapes out. To make very large pieces, you may need to patch two pieces of foam together. Preferably, attach the pieces where it is inconspicuous, or can be integrated into the design. For example, creating a seam down the center of a breastplate. You can use a number of other materials to create your costume armor, such as cardboard, Wonderflex or anything else that suits your means. The same steps can be applied to any material. To make your foam go further, trace large pieces first and then fit the smaller ones in around them.

“Emboss” the armor if necessary. Lightly sketch the designs with a ball-point pen or a dull knife and when you’re happy, go over them several times while pressing hard to engrave them into the foam. It’s much easier to draw on the foam while it’s flat and not yet assembled. Just be sure not to tear the materials.

Assembling the Armor

Shape and contour the craft foam to your body. Since it’s flexible, this will simply be a matter of gluing it into curves in many places. In some places, however, you will want to mold the foam into shapes that hold on their own. This is done by holding the foam near a steady, safe heat source (such as a heat gun or stove) to soften it and then manually bending it over another object such as a liter bottle or rolling pin. You will only have a few seconds to do this, so work quickly. It’s best to test your technique on a few scrap pieces beforehand so that you learn how to heat the foam without causing it to scorch, shrink, or bubble. If you want you can also try using a hair dryer on high heat or an iron to heat the foam. If you don't have a heat source you can try wrapping the armor around a rounded object for a couple days to create the desired curves. You can create arm or leg pieces around a Pringles can and use a rubber band to hold them in place.

Glue the craft foam together wherever the pieces were designed to overlap. White school glue is fine for this. In some cases (ex. in places with lots of overlap or dramatic curves), it will make sense to do this after the pieces have already been heat-molded to keep from putting undue strain on the material. However, when you’re dealing with pieces that require minimal molding or don’t overlap in a way that constricts their movement too much, you might want to glue them together before molding them.

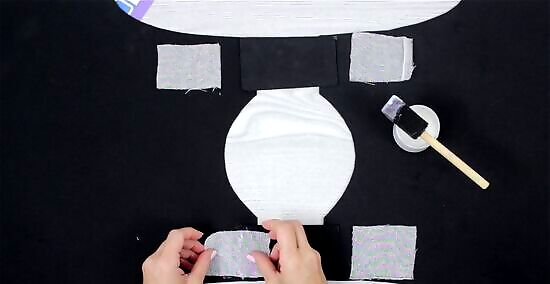

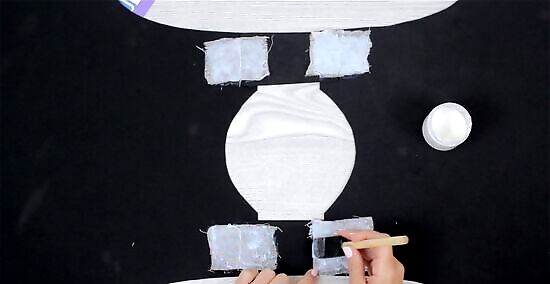

Reinforce and stiffen the armor. Flip joined pieces over, paint them with glue, and smooth a gauzy fabric (ex. cotton crinkle gaze or cheesecloth) over them, making sure to work into creases and curves with a pointed edge. After it dries, cut away the excess and apply one more coat of glue.

Work in sections. If you are dealing with lots of pieces, you might have to assemble a number of them just to make one section of one part of the armor. Think about where it makes the most sense to join subsections together before connecting them to make larger pieces.

Leave openings. Since the foam is flexible, you will have quite a bit of leeway with this: a well-placed seam that you can force your way into and out of would be no problem for craft foam. For traditional-style armor, however, you will want to mimic the way that real armor is assembled by connecting various pieces with leather or fabric straps that you can untie/unbuckle as necessary.

Decide how to attach the armor to your body. Unless you’ve made a full, one-piece suit, you will likely have to attach separate sections differently. Wearing a tight-fitting outfit underneath the armor and attaching Velcro to a number of places as anchor points would work well provided that you line everything up correctly. You might, for example, stick double-sided Velcro to the necessary parts of your under-outfit. Press the armor onto these points in front of a mirror until the look right. Then more firmly attach each Velcro half to its respective part of the ensemble using thread or a strong glue to hold the pieces in place.

Painting Your Armor

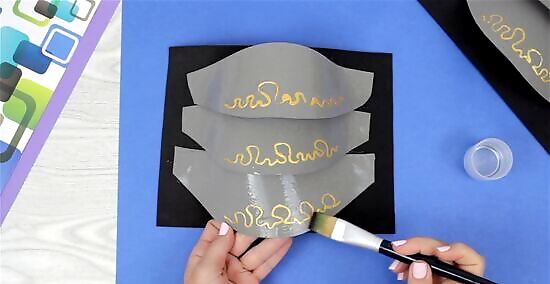

Apply raised designs if necessary. If you embossed a design into your armor, simply draw over it with fabric paint from a squirt-tube to create a raised design. You might have to do this more than once to make it more visible. Since the results will be thick, allow this to dry overnight.

Seal the foam. Since the foam is spongy, you will need to seal it before applying any glue. One suggested mixture is 1 part school glue or Sobo glue, 1 part flexible fabric glue, and 2 parts water. Apply and dry thin coats until sealant no longer forms holes where air bubbles from the foam pop through. This may take as many as 7 or 8 coats, but because the layers are thin, the dry time shouldn’t be unbearable. Don’t allow debris to stick to the glue or it will produce bumps in the armor.

Paint over the back of the armor with acrylic paint if necessary. If the armor sticks out in places (leaving the underside exposed), painting the back will give it a more professional look.

Paint the front of the armor. Because the foam will bend and move with your body, ordinary paints will crack. On a piece of scrap foam, experiment with flexible craft paints (ex. fabric paint) to see what will work for your design. Be sure to apply the paint evenly to prevent streaking and work it into and cracks or crevices.

Give the armor a weathered look. This can be done by brushing dark acrylic paint (ex. a mixture of black and green for a tarnished copper look) over your armor and wiping most of it away before it dries so that hints of it remain in the cracks.

Comments

0 comment