views

X

Trustworthy Source

PubMed Central

Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health

Go to source

While each type of bipolar disorder is serious, they’re also treatable, usually through a combination of prescription medication and psychotherapy. If you think that someone you know has bipolar disorder, read on to find out how to support your loved one.

Learning About Bipolar Disorder

Look for unusually intense “mood episodes.” A mood episode represents a significant, even drastic, change from a person’s typical mood. In popular language, these may be called “mood swings.” People who suffer from bipolar disorder may switch rapidly between mood episodes, or their moods may persist for weeks or months. There are two basic types of mood episode: extremely elevated, or manic episodes, and extremely depressed, or depressive episodes. The person may also experience mixed episodes, in which symptoms of mania and depression occur at the same time. A person with bipolar disorder may experience periods of “normal” or relatively calm moods in between intense mood episodes.

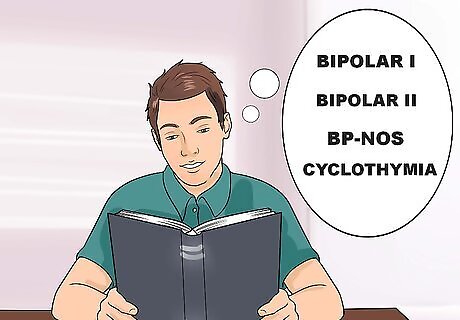

Educate yourself about the multiple types of bipolar disorder. There are four basic types of bipolar disorder that are regularly diagnosed: Bipolar I, Bipolar II, Bipolar Disorder Not Otherwise Specified, and Cyclothymia. The type of bipolar disorder a person is diagnosed with is determined by its severity and duration, as well as how quickly the mood episodes cycle. A trained mental health professional must diagnose bipolar disorder; you cannot do it yourself and should not attempt to do so. Bipolar I Disorder involves manic or mixed episodes that last for at least seven days. The person may also have severe manic episodes that put them in enough danger to require immediate medical attention. Depressive episodes also occur, usually lasting at least two weeks. Bipolar II Disorder involves episodes of 'hypomania', which rarely escalates to full-blown mania, and more lasting episodes of depression. Hypomania is a milder manic state, in which the person feels very “on,” is extremely active, and appears to require little to no sleep; other symptoms of mania such as racing thoughts, rapid speech, and flights of ideas might also be present, but unlike those in manic states, people experiencing hypomania do not generally lose touch with reality or the ability to function. Untreated, this type of manic state may develop into severe mania. The depressive episodes in Bipolar II are generally assumed to be more severe and lasting than the depressive episodes in Bipolar I. It is important to note that a wide range of symptoms might be associated with both types I and II, and the experiences of every individual sufferer are different, so while conventional wisdom dictates as much, this is often, but not always the case. Bipolar Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (BP-NOS) is a diagnosis made when symptoms of bipolar disorder are present but don’t meet the rigid diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5 (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). These symptoms are still not typical for the person’s “normal” or baseline range. Cyclothymic disorder or cyclothymia is a mild form of bipolar disorder. Periods of hypomania alternate with shorter, milder episodes of depression. This must persist for at least two years to meet diagnostic criteria. A person with bipolar disorder may also experience “rapid cycling,” in which they experience four or more mood episodes within a 12-month period. Rapid cycling appears to affect slightly more women than men, and it can come and go.

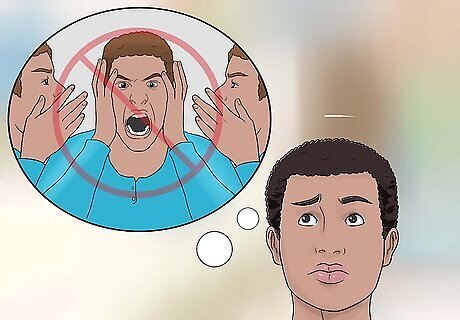

Know how to recognize a manic episode. How a manic episode manifests may vary from person to person. However, it will represent a dramatically more elevated or “revved up” mood from the person’s “normal” or baseline emotional state. Some symptoms of mania include: Feelings of extreme joy, happiness, or excitement. A person having a manic episode may feel so “buzzed” or happy that even bad news cannot damage their mood. This feeling of extreme happiness persists even without apparent causes. Overconfidence, feelings of invulnerability, delusions of grandeur. A person having a manic episode may have an overinflated ego or higher sense of self-esteem than is typical for them. Thy may believe they can accomplish more than is feasible, as though absolutely nothing can get in their way. They may imagine that they have special connections to figures of importance or supernatural phenomena. Increased, sudden irritability and anger. A person having a manic episode may snap at others, even without provocation. They are likely to be more “touchy” or easily angered than is usual in their “typical” mood. Hyperactivity. The person may take on multiple projects at once, or schedule more things to do in a day than reasonably can be accomplished. They may choose to do activities, even seemingly purposeless ones, instead of sleeping or eating. Increased talkativeness, scattered speech, racing thoughts. The person having a manic episode will often have difficulty collecting their thoughts, even though they are extremely talkative. They may jump very quickly from one thought or activity to another. Feeling jittery or agitated. The person may feel agitated or restless. They may be easily distracted. Sudden increase in risky behavior. The person may do things that are unusual for their normal baseline and pose a risk, such as having unsafe sex, going on shopping sprees, or gambling. Risky physical activities such as speeding or undertaking extreme sports or athletic feats -- especially ones the person is not adequately prepared for -- may also occur. Decreased sleeping habits. The person may sleep very little, yet claim to feel rested. They may experience insomnia or simply feel like they don’t need to sleep.

Know how to recognize a depressive episode. If a manic episode makes a person with bipolar disorder feel like they’re “on top of the world,” a depressive episode is the feeling of being crushed at the bottom of it. The symptoms may vary between people, but there are some common symptoms to look out for: Intense feelings of sadness or despair. Like the feelings of happiness or excitement in the manic episodes, these feelings may not appear to have a cause. The person may feel hopeless or worthless, even if you make attempts to cheer them up. Anhedonia. This is a fancy way of saying that the person no longer shows interest or enjoyment in things thy used to enjoy doing. Sex drive may also be lower. Fatigue. It’s common for people suffering from major depression to feel tired all the time. They may also complain of feeling sore or achy. Disrupted sleep pattern. With depression, a person’s “normal” sleep habits are disrupted in some way. Some people sleep too much while others may sleep too little. Either way, their sleep habits are markedly different from what is “normal” for them. Appetite changes. People with depression may experience weight loss or weight gain. They may overeat or not eat enough. This varies depending on the person and represents a change from what is “normal” for them. Trouble concentrating. Depression can make it difficult to focus or make even small decisions. A person may feel nearly paralyzed when they’re experiencing a depressive episode. Suicidal thoughts or actions. Don’t assume that any expressions of suicidal thoughts or intentions are “just for attention.” Suicide is a very real risk for people with bipolar disorder. Call 911 or emergency services immediately if your loved one expresses suicidal thoughts or intents.

Read all you can about the disorder. You’ve taken an excellent first step by looking up this article. The more you know about bipolar disorder, the better you’ll be able to support your loved one. If you’re a friend or family member of someone with bipolar disorder, your support can help them manage their symptoms. Below are a few resources you may consider: The National Institute of Mental Health is an excellent place to start for information on bipolar disorder, its symptoms and possible causes, treatment options, and how to live with the illness. The Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance offers resources for individuals living with bipolar disorder and their loved ones. Marya Hornbacher’s memoir Madness: A Bipolar Life talks about the author’s lifelong struggle with bipolar disorder. Dr. Kay Redfield Jamison’s memoir An Unquiet Mind talks about the author’s life as a scientist who also has bipolar disorder. While each person’s experience is unique to them, these books may help you to understand what your loved one is going through. Bipolar Disorder: A Guide for Patients and Families, by Dr. Frank Mondimore, can be a good resource for how to care for your loved one (and yourself). The Bipolar Disorder Survival Guide, by Dr. David J.Miklowitz, is geared toward helping people with bipolar disorder, and their loved ones manage the illness. The Depression Workbook: A Guide for Living with Depression and Manic Depression, by Mary Ellen Copeland and Matthew McKay, is geared toward helping people diagnosed with bipolar disorder maintain mood stability with various self-help exercises.

Reject some common myths about mental illness. Mental illness is commonly stigmatized as something “wrong” with the person. It may be viewed as something they could just “snap out of” if they “tried hard enough” or “thought more positively.” The fact is, these ideas are simply not true. Bipolar disorder is the result of complex interacting factors including genetics, brain structure, chemical imbalances in the body, and sociocultural pressures. A person with bipolar disorder can’t just “stop” having the disorder. However, bipolar disorder is also treatable. Consider how you would speak to someone who had a different sort of illness, such as cancer. Would you ask that person, “Have you ever tried just not having cancer?” Telling someone with bipolar disorder to just “try harder” is equally incorrect. Medication and therapy can help manage the symptoms of bipolar disorder, but the disorder can last a lifetime. There’s a common misconception that bipolar is rare. In fact, about 6 million American adults suffer from some type of bipolar disorder. Even famous individuals such as Stephen Fry, Carrie Fisher, and Jean-Claude Van Damme have been open about being diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Another common myth is that manic or depressive mood episodes are “normal” or even a good thing. While it’s true that everyone has their good days and bad days, bipolar disorder causes shifts in mood that are far more extreme and damaging than the typical “mood swings” or “off days.” They cause significant dysfunction in the person’s daily life. A common mistake is to confuse schizophrenia with bipolar disorder. They are not at all the same illness, although they have a few symptoms (such as depression) in common. Bipolar disorder is characterized principally by the shift between intense mood episodes. Schizophrenia generally causes symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized speech, which do not often appear in bipolar disorder. It is possible for someone with schizoaffective disorder, to have the symptoms of both though. Many people believe that people with bipolar disorder or depression are dangerous to others. The news media is particularly bad about promoting this idea. In reality, research shows that people with bipolar disorder don’t commit any more violent acts than people without the disorder. People with bipolar disorder may be more likely to consider or attempt suicide, however.

Talking With Your Loved One

Avoid hurtful language. Some people may jokingly say they’re “a little bipolar” or “schizo” when describing themselves, even if they have not been diagnosed with a mental illness. In addition to being inaccurate, this type of language trivializes the experience of people who have bipolar disorder. Be respectful when discussing mental illness. It’s important to remember that people are more than the sum of their illness. Don’t use totalizing phrases such as “I think you’re bipolar.” Instead, say something like, “I think you may have bipolar disorder.” Referring to someone “as” their illness reduces them to one element about them. This promotes the stigma that all too often still surrounds mental illness, even if you don’t mean it that way. Trying to comfort the other person by saying “I’m a little bipolar too” or “I know how you feel” can do more damage than good. These things may make the other person feel as though you aren’t taking their illness seriously.

Talk about your concerns with your loved one. You might be worried about talking to your loved one for fear of upsetting them. It’s actually very helpful and important for you to talk with your loved one about your concerns. Not talking about mental illness promotes the unfair stigma around it and may encourage people with a disorder to wrongly believe that they are “bad” or “worthless” or should feel ashamed of their illness. When approaching your loved one, be open and honest, and show compassion. Supporting someone who suffers from bipolar disorder can help them recover and manage their illness. Reassure the person that they aren’t alone. Bipolar disorder can make a person feel very isolated. Tell your loved one that you are here for them and want to support them in any way you can. Acknowledge that your loved one’s illness is real. Trying to minimize your loved one’s symptoms won’t make them feel better. Instead of trying to tell the person that the illness is “no big deal,” acknowledge that the condition is serious but treatable. For example: “I know that you have a real illness and that it causes you to feel and do things that aren’t like you. We can find help together.” Convey your love and acceptance to the person. Particularly while in a depressive episode, the person may believe that they are worthless or ruined. Counter these negative beliefs by expressing your love and acceptance of the person. For example: “I love you, and you are important to me. I care about you, and that’s why I want to help you.”

Use “I” statements to convey your feelings. When talking with another person, it’s crucial that you not seem as though you’re attacking or judging your loved one. People with mental illness may feel as though the world is against them. It’s important to show that you’re on your loved one’s side and that you’re there to support them and help them recover. For example, say things such as “I care about you and am worried about some things I’ve seen.” There are some statements that come across as defensive. You should avoid these. For example, avoid saying things like “I’m just trying to help” or “You just need to listen to me.”

Avoid threats and blame. You may be concerned about your loved one’s health, and feel willing to make sure they get help “by any means necessary.” However, you should never use exaggerations, threats, “guilt trips,” or accusations to convince the other person to seek help. These will only encourage the other person to believe that you see something “wrong” with them and that you’re not there to help or support them. Avoid statements such as “You’re worrying me” or “Your behavior is odd.” These sound accusative and may shut the other person down. Statements that attempt to play on the other person’s sense of guilt are also not helpful. For example, don’t try to use your relationship as leverage to get the other person to seek help by saying something like, “If you really loved me you would get help” or “Think about what you’re doing to our family.” People with bipolar disorder often struggle with feelings of shame and worthlessness, and statements like these will only make that worse. Avoid threats. You cannot force the other person to do what you want. Saying things like “If you don’t get help I’m leaving you” or “I won’t pay for your car anymore if you don’t get help” will only stress the other person out, and the stress may trigger a severe mood episode.

Frame the discussion as a concern about health. Some people may be reluctant to acknowledge that they have an issue. When someone with bipolar is experiencing a manic episode, they are often feeling so “high” that it’s hard to admit that there’s any problem. When a person is experiencing a depressive episode, they may feel like they have a problem but not be able to see any hope for treatment. You can frame your concerns as medical concerns, such as the high risk of self-harm and suicide that bipolar disorder can cause, which may help. For example, you can reiterate the idea that bipolar disorder is an illness just like diabetes or cancer. Just as you would encourage the other person to seek treatment for cancer, you want them to seek treatment for this disorder. If the other person is still reluctant to acknowledge there’s an issue, you can consider suggesting they visit a doctor for a symptom that you’ve noticed, rather than for a “disorder.” For example, you may find that suggesting the other person see a doctor for insomnia or fatigue may be helpful in getting them to seek help.

Encourage the other person to share their feelings and experiences with you. It’s easy for a conversation to express your concern to turn into you preaching at your loved one. To avoid this, invite your loved one to tell you about what they are thinking and feeling in their own words to allow for a genuine conversation about their illness. Remember: while you may be affected by this person’s disorder, it isn’t about you. For example, once you’ve shared your concerns with the person, say something like, “Would you like to share what you’re thinking right now?” or “Now that you’ve heard what I wanted to say, what do you think?” Don’t assume you know how the other person feels. It can be easy to say something like “I know how you feel” as reassurance, but in reality, this can sound dismissive. Instead, say something that acknowledges the other person’s feelings without claiming them as your own: “I can see why that would make you feel sad.” If your loved one is resistant to the idea of acknowledging that they have a problem, don’t argue about it. You can encourage your loved one to seek treatment, but you can’t make it happen.

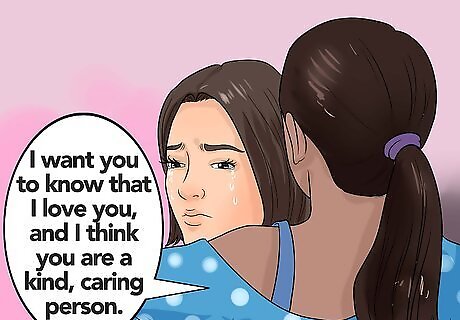

Don’t dismiss your loved one’s thoughts and feelings as “not real” or not worth considering. Even if a feeling of worthlessness is caused by a depressive episode, it feels very real to the person experiencing it. Outright dismissing a person’s feelings will encourage them not to tell you about them in the future. Instead, validate the person’s feelings and challenge negative ideas at the same time. Everyone who suffers from bipolar disorder has a different experience and recovery and management can be helped by avoiding negative influences. For example, if your loved one expresses the idea that nobody loves them and they’re a “bad” person, you could say something like this: “I know you feel that way, and I’m so sorry that you’re experiencing those feelings. I want you to know that I love you, and I think you are a kind, caring person.”

Encourage your loved one to take a screening test. Mania and depression are both hallmarks of bipolar disorder. The Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance’s website offers free, confidential online screening tests for mania and depression. Taking a confidential test in the privacy of one’s own home may be a lower-stress way for the person to understand the need for treatment.

Emphasize the need for professional help. Bipolar disorder is a very serious illness. Untreated, even mild forms of the disorder can get worse. On the other hand, treatment can be very helpful and can contribute to better relationships and quality of life. Encourage your loved one to seek treatment immediately. Visiting a general practitioner is often the first step. A physician can determine whether the person should be referred to a psychiatrist or other mental health professional. A mental health professional will usually offer psychotherapy as part of a treatment plan. There is a wide range of mental health professionals who offer therapy, including psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, licensed clinical social workers, and licensed professional counselors. Ask your doctor or hospital to recommend some in your area. Treatment often consists of therapy to practice emotional regulation coupled with psychiatry to help the brain maintain a balance. If it’s determined that medication is necessary, your loved one may see a physician, a psychiatrist, a psychologist who’s licensed to prescribe medicine or a psychiatric nurse to receive prescriptions. LCSWs and LPCs can offer therapy but cannot prescribe medicine.

Supporting Your Loved One

Understand that bipolar disorder is a lifelong illness. A combination of medication and therapy can greatly benefit your loved one. With treatment, many people with bipolar disorder experience significant improvement in their function and mood. However, there is no “cure” for bipolar disorder, and symptoms can recur throughout one’s life. Stay patient with your loved one.

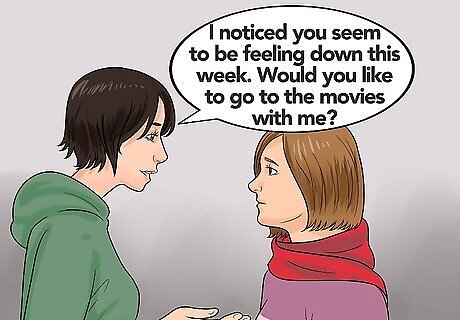

Ask how you can help. Particularly during depressive episodes, the world may feel overwhelming to a person with bipolar disorder. Ask the other person what would be helpful to them. You can even offer specific suggestions if you have a sense of what is most affecting your loved one. If they feel supported, they may be better able to manage their mental illness. For example, you could say something like, “It seems like you’ve been feeling very stressed lately. Would it be helpful if I babysat your kids and gave you an evening of ‘me time’?” If the person has been experiencing major depression, offer a pleasant distraction. Don’t treat the person as fragile and unapproachable just because they have an illness. If you notice that your loved one has been struggling with depressive symptoms (mentioned elsewhere in this article), don’t make a big deal of it. Just say something like, “I noticed you seem to be feeling down this week. Would you like to go to the movies with me?”

Keep track of symptoms. Keeping track of your loved one’s symptoms can help in several ways. First, it can help you and your loved one learn warning signs of a mood episode. It can provide helpful information for a physician or mental health professional. It can also help you learn potential triggers for manic or depressive episodes. Warning signs of mania may include: sleeping less, feeling “high” or excitable, increased irritability, restlessness, and an increase in the person’s activity level. Warning signs of depression may include: fatigue, disturbed sleeping patterns (sleeping more or less), difficulty focusing or concentration, lack of interest in things the person usually enjoys, social withdrawal, and changes in appetite. The Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance has a personal calendar for tracking symptoms. It may be helpful to you and your loved one. Common triggers for mood episodes include stress, substance abuse, and sleep deprivation.

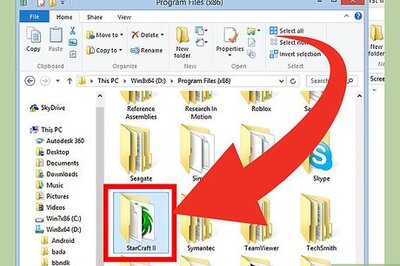

Ask whether your loved one has taken their medication. Some people may benefit from a gentle reminder, particularly if they are experiencing a manic episode in which they may become fitful or forgetful. The person may also believe they are feeling better and so stop taking the medication. Help your loved one stay on track, but don’t sound accusative. For example, a gentle statement such as “Have you taken your medication today?” is fine. If your loved one says they’re feeling better, you may find it helpful to remind them about the benefits of medication: “I’m glad to hear you’re feeling better. I think part of that is that your medication is working. It’s not a good idea to stop taking it if it’s working for you, right?” It can take several weeks for medications to begin working, so have patience if your loved one’s symptoms don’t seem to be improving.

Encourage the other person to stay healthy. In addition to regularly taking prescribed medication and seeing a therapist, staying physically healthy can help reduce symptoms of bipolar disorder. People with bipolar disorder are at a higher risk of obesity. Encourage your loved one to eat well, get regular, moderate exercise, and keep a good sleep schedule. People with bipolar disorder often report unhealthy eating habits, including not eating regular meals or eating unhealthy food, possibly because of being on low income after the onset of the illness. Encourage your loved one to eat a balanced diet of fresh fruits and vegetables, complex carbohydrates such as beans and whole grains, and lean meats and fish. Consuming omega-3 fatty acids may help protect against bipolar symptoms. Some studies suggest that omega-3s, especially those found in coldwater fish, help decrease depression. Fish such as salmon and tuna, and vegetarian foods such as walnuts and flaxseed, are good sources of omega-3s. Encourage your loved one to avoid too much caffeine. Caffeine may trigger unwanted symptoms in people with bipolar disorder. Encourage your loved one to avoid alcohol. People with bipolar disorder are five times more likely to abuse alcohol and other substances than those without a disorder. Alcohol is a depressant and can trigger a major depressive episode. It can also interfere with the effects of some prescription medications. Regular moderate exercise, especially aerobic exercise, may help improve mood and overall functioning in people with bipolar disorder. It’s important to encourage your loved one to exercise regularly; people with bipolar disorder often report poor exercise habits.

Care for yourself, too. Friends and families of people with bipolar disorder need to make sure that they take care of themselves, too. You can’t support your loved one if you’re exhausted or stressed out. Studies have even shown that if a loved one is stressed out, the person with bipolar disorder may have more difficulty sticking to the treatment plan. Caring for yourself directly helps your loved one, too. A support group may help you learn to cope with your loved one’s illness. The Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance offers an online support group and local peer support groups. The National Alliance on Mental Illness also has a variety of programs. Make sure that you get enough sleep, eat well, and get regular exercise. Keeping these healthy habits may also encourage your loved ones to stay healthy too. Take actions to reduce your stress. Know your limits, and ask others for help when you need it. You may find that activities such as meditation or yoga are helpful in reducing feelings of anxiety.

Watch for suicidal thoughts or actions. Suicide is a very real risk for people with bipolar disorder. People with bipolar disorder are more likely to consider or attempt suicide than people with major depression. If your loved one makes references to suicide, even casually, seek immediate help. Don’t promise to keep these thoughts or actions secret. If the person is in immediate danger of harm, call 911 or emergency services. Suggest that your loved one call a suicide hotline such as the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (988). You can also suggest your local suicide hotline number for those outside the US. Reassure your loved one that you love him/her and that you believe their life has meaning, even if it may not seem that way to the person right now. Don’t tell your loved one not to feel a certain way. The feelings are real, and they can’t change them. Instead, focus on actions that the person can control. For example: “I can tell this is hard for you, and I’m glad you’re talking to me about it. Keep talking. I’m here for you.”

Comments

0 comment