views

Building Your Characters

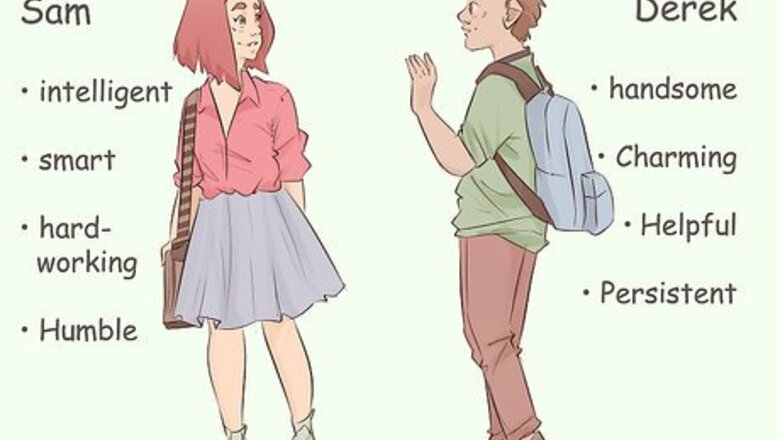

List out traits you want to see in your main characters. The best characters in a love story are ones with depth. Think about what traits you want to see in your characters, and why those traits are significant to your story. Then, make a list for each character and note 5-6 specific character traits you want to see in them. Use these as a guide while you write. For example, your list for your protagonist may include stubborn, intelligent but not street-smart, slow to trust but incredibly loyal once trust is earned, overcoming a rough past, and outspoken. Use these traits to inform this character's dialogue and actions in the scenes you write. Think about traits that help the development of your story, not just your romance. Your protagonist may be a strong woman overcoming emotional scars, but don’t make her that just so her match can break down her walls. Use her emotional past to develop a holistic character. Think about Cleopatra and Mark Antony. Their love story has been chronicled in literature and film. In the most lasting depictions, Cleopatra is a strong leader with political ambitions that extend beyond her love. The love story is engaging, but so is the character.

Create characters with both complementary and conflicting traits. Your character’s traits should challenge each other. Avoid creating a world where two people who are perfectly compatible meet, are happy, and never grow or change. This is a common pitfall that makes for a bland story. For example, your characters may both be neurosurgeons at the top of their game, but 1 of the characters might be extremely high-strung and serious while the other character is laid back and makes a joke out of everything. Marie and Pierre Curie, for example, had a shared interest in their scientific work. The politics of the time, though, meant that Marie had to push a lot harder to get recognition and support for her work. Their love story is remembered along with their science because of what they shared and what they had to fight for.

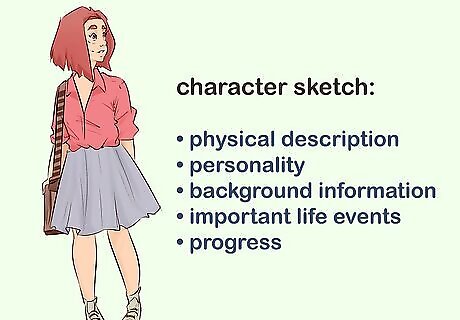

Write out sketches for your main characters. Once you have the framework for your main characters, a character sketch can help you fill in the details. These can take the forms of outlines, spec pages, drawings, or even short stories to describe how your characters developed. A character sketch should include the basics of each character’s physical description, their personality, information about their background and transformative life events, and some details about how you want your character to progress in your story. A character sketch is a guideline. You don’t need everything you sketch to be in your story. You’re also allowed to change your character if your original sketches don’t fit the progress of your story.

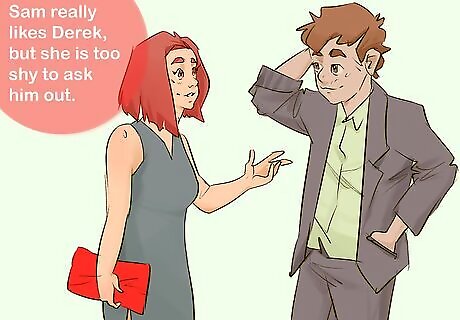

Write your love interest with your protagonist in mind. You write your protagonist to be interesting and relatable for your audience. The love interest should be written for your protagonist. It’s easy to write a love interest that serves a fantasy for your audience’s romantic wish fulfillment, but these characters rarely challenge your protagonist or progress your story. Think about everyday relationships. What you are and are not willing to accept in a partner likely different from your friends or neighbors. Write the partner that works for your protagonist, not for all your readers. Write a partner that is right for your protagonist, but not so right that your conflict seems forced. Consider real-life relationships. People in love often disagree, butt heads, and question their relationship. Your lovers should be a good match, not a perfect match.

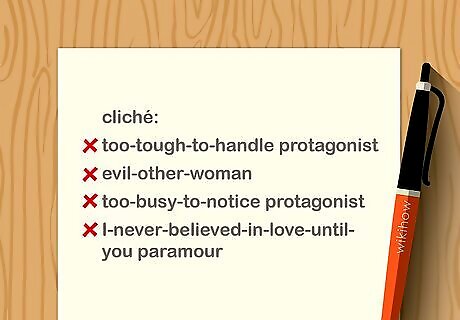

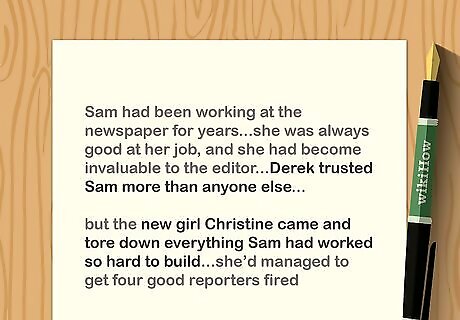

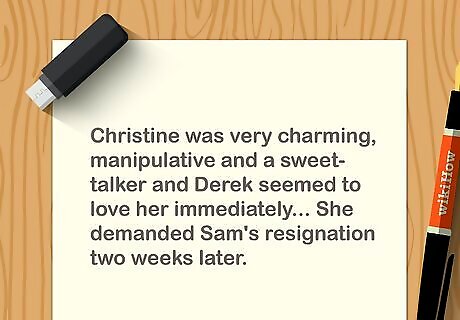

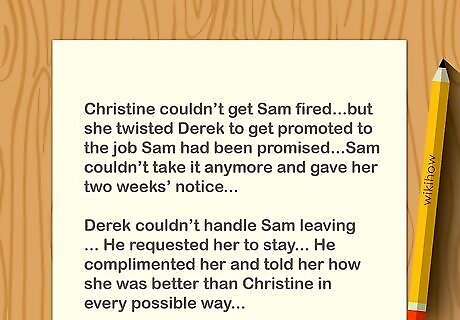

Avoid cliché character archetypes. More than some other types of fiction, love stories are susceptible to using the same types of characters over and over. Avoid cliché characters that you’ve read before in other love stories. If you do want to use an archetype, try giving it a twist by changing 1 or more if the key traits. Some common character archetypes include: The too-tough-to-handle protagonist who only opens up when a foe makes them need a hero’s rescue. The evil-other-woman (like former lover or ex-spouse) that tries to ruin the protagonist’s chance of finding true love. The too-busy-to-notice protagonist that doesn’t realize when the love of their life enters the picture. The I-never-believed-in-love-until-you paramour that was hardened to love until the protagonist entered their life.

Determining Your Plot

Figure out if your love story will be your main story. A love story can be your main focus or it can be part of a larger tale. Decide whether you want your love story to be the main focus of your writing, or if you want it to enhance your main story. Framing a love story as part of a larger story can create a more realistic, relatable feeling to your writing. Focusing primarily on romance can be sweeping, epic, and more escapist. Neither is inherently better or worse, they’re just different styles. For example, Love in the Time of Cholera is driven by its love story, but it also deals with themes of social strife, warfare, disease, aging, and death. It's also defined not just by its love story but by its magical realism, making it part of a strong Latino literary tradition.

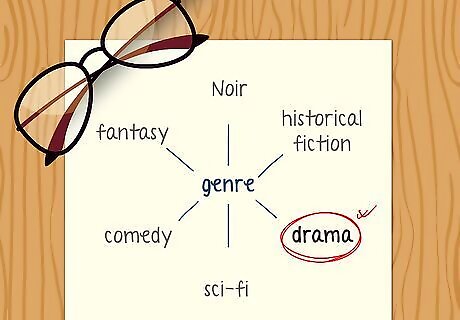

Pick the genre in which you want to set your story. Love stories don’t have to be romance novels. They play out across the daily lives of your characters and can work in any type of genre. Decide whether you want to write a more traditional romance or if you want to frame your story in another genre. To get an idea of how love stories are framed across genres, read books and short stories from the genres in which you’re interested. Noir, sci-fi, fantasy, historical fiction, and comedic writing are some good genres to explore. Pay attention to how different authors in these genres develop different conventions of a love story.

Decide what kind of emotional ending you want for your story. Do you want your characters to get their happily-ever-after? Will they learn that love isn’t enough? Do you want something vague and open-ended? Deciding what kind of emotional resolution you want at the end of your story helps sculpt your plot and narrative. You can change this as you progress with your story if find that a different ending fits how your plot and characters develop. This should be a guide, but it doesn’t need to be a rule.

Consider whether you want your story to have a larger message. A love story for the sake of a love story can be a beautiful thing if that’s what you want to write. However, many modern romance authors are considering the social contexts of what they are putting out, such as race, gender, and class. Think about whether you want your story to have a larger message. There is no right or wrong answer to this, but it is important to consider the message you’re putting out. Love stories commonly deal with topics like social inequity, body image, gender equality, sexual orientation, class difference, and ethnic identity.

Crafting Your Story

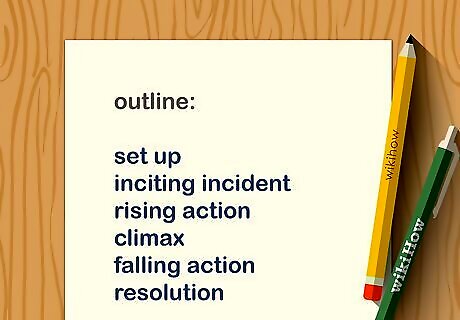

Outline your plot. Not every writer likes to work with outlines, and that’s fine. In love stories, though, an outline can help you stick to your plot without getting too swept up in romance. Outline your story before you start writing, making notes of significant events and plot points in the order in which you want them incorporated in your story. Outlines can be minimal or more fleshed out. Play around with the amount of detail to see what works best for you as you’re writing. Outlines, like character sketches, are guides rather than rulebooks. Your story is allowed to progress outside of what you’ve outlined if that feels natural for your plot and characters.

Create a sense of anticipation. What makes it so satisfying when your lovers come together is the emotional build-up you create to that point. Build a sense of anticipation by creating natural obstacles for your lovers so that their romance is the satisfying conclusion of a long emotional journey. You don’t want to introduce your lovers too soon, you don’t want them to fall in love too soon, and you don’t want them to be too happy together too soon. Love stories should explore a full range of emotion. Put obstacles in place that make your lovers happy, angry, sad, conflicted, jealous, etc.

Separate your lovers after you bring them together. Lovers that find one another and stay together don’t usually make for an interesting story. After you first bring your lovers together, find a reason to separate them. This not only creates drama, but it also gives your lovers space to long for one another and consider the dynamics of their relationship. Think about a book like Pride and Prejudice as an example. Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy are brought together and separated multiple times. During each encounter, their feelings change and they think of one another a little more.

Make a believable climax for your lovers and bring them back together. It’s a common trap to have your lovers’ climatic scene grow from a misunderstanding. You see that on TV and in movies. However, ballooning conflict due to a misunderstanding can make your characters seem irrational and overly-emotional. Instead, create real obstacles that make their future together questionable for your readers, but them bring them back together in the end. An example of a common, overused misunderstanding is one lover getting upset when they walk in on a former love interest kissing their new lover. It’s dramatic and irrational to have your protagonist fume over an action their paramour couldn’t control. Instead, think of an obstacle like a partner getting a job on a different continent, or one partner really wanting kids and the other not wanting them at all. These are commonly used, too, but they create a sense of real emotional conflict.

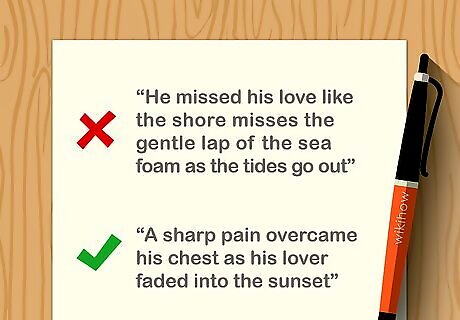

Use literary devices sparingly. Love stories are often associated with long prose and flowery writing. Don’t be afraid to use a lyrical writing style. However, too many metaphors, symbols, and other literary devices can make a story wordy and difficult to follow. Use literary devices when they enhance your reader's understanding of emotions or events in the story. Don't feel pressured to put them in to make your writing sound more romantic, though. It is important to keep the content of your story plausible. For example, “He missed his love like the shore misses the gentle lap of the sea foam as the tides go out,” is a romantic-sounding simile, but it doesn’t offer clarity. “A sharp pain overcame his chest as his lover faded into the sunset,” is familiar to your reader, since most people understand some level of chest pain. In this case, the latter is more relatable. When in doubt, ask yourself, “Will this help my readers better understand what’s going on?”

Offer a sense of resolution at the end. Regardless of whether your lovers end up together or not, offer your readers a sense of resolution at the end. Your characters should develop and grow over the course of your story in a way that sets them up to move forward, either together or alone, by your last page. For example, “When Jessie left, Jordan was filled with a sense of despair and dread that overcame her so completely she never went anywhere or did anything again,” is an unsatisfying ending. Instead, make it bittersweet. When Jessie leaves, Jordan can absolutely be hurt and afraid. But she should also look out with nervous optimism about the new opportunity in front of her.

Edit your story to avoid overwriting. Once you’ve written your story, go through an edit to look for unnecessary descriptors and excessive details that don’t contribute to your story. Don’t use flowery language just for the sake of it. Unless your adjectives and adverbs directly help your reader understand what’s going on, or the emotion and intention behind an action, cut them. Don’t use words without understanding their connotation. If you have a naturally fair-skinned and generally healthy character, for example, you wouldn't call them "pallid." While pallid does mean pale, it's most often used as a medical term in association with illness and poor health. Instead, "fair," "ivory," or "porcelain," would all work.

Comments

0 comment