views

- Mature clams release sperm and egg cells into the open water for fertilization (broadcast spawning). Some hermaphroditic clams can fertilize their own eggs.

- Fertilized eggs grow into veliger larvae (mollusk larvae with swimming flaps) within 48 hours and float in open water until they settle on the seafloor.

- Juvenile clams bury themselves under the seafloor to grow into adults. Only about 1% of clams that survive to the juvenile stage will make it to full adulthood.

- Clams grow their shells from the inside out by releasing proteins and calcium carbonate from their mantle tissue (the outer tissue that connects with the shell).

Reproductive Process

Mature clams release sperm and eggs into the water for fertilization. Clam reproduction happens between May and October when water temperatures reach about 68 °F (20 °C), but this varies slightly based on location and species. The warm water triggers males and females to release their gametes (reproductive cells) through their siphon valves into the water column, where sperm cells bump into and fertilize egg cells by chance. This reproductive method is called broadcast spawning. Fertilized eggs begin dividing rapidly, especially in warmer water. In just a few hours, they form a multi-celled embryo called a morula. Morula are named after the Latin word for mulberry, which is what they look like at this early stage.

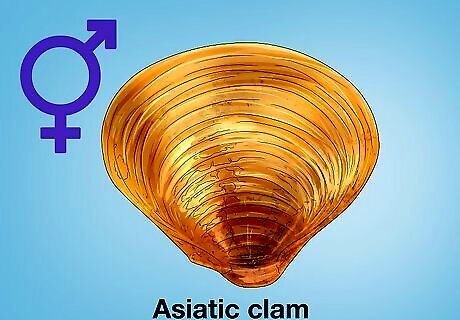

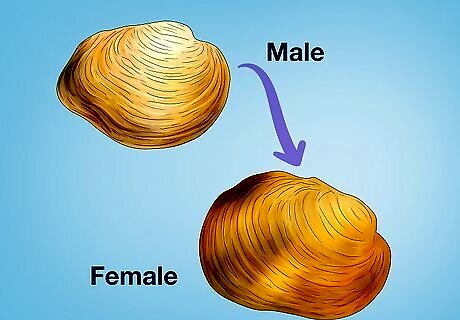

Some clams are male or female while some are hermaphroditic. A hermaphrodite is an animal that has both male and female sex organs or other sexual characteristics. The Asiatic clam, for example, is a hermaphrodite that can release both sperm and egg cells. Hermaphroditic clams can self-fertilize when local colony populations are low and regrow their population rapidly. Some hermaphroditic clams release their sperm and egg cells at separate times to increase the chance of reproducing with a separate clam. Many gonochoric (non-hermaphroditic) species of clams begin life as male and transition to female when they’re larger and mature.

Life Cycle of a Clam

Morula embryos develop into trochophore larvae in as little as 18 hours. Trochophore larva look like tiny, plankton-like creatures that float in the open water and are only 0.1 mm (0.0039 in) long (the width of a human hair). The trochophores develop hair-like cilia that help them move as they grow, but they’re still largely at the mercy of ocean currents. The term “trochophore” can refer to any mollusk larvae that drift in the water like plankton, are shaped like spheres, and have cilia hairs for propulsion. Warmer water encourages faster growth. Trochophores can form between 18 and 48 hours after an egg cell is fertilized.

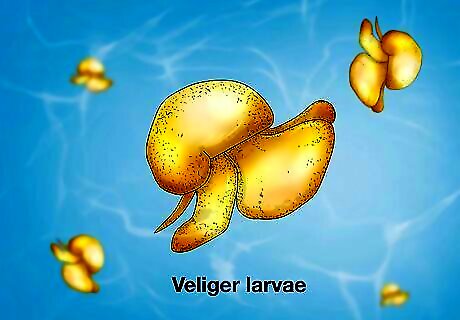

The baby clams grow into veliger larva after a few more days. Veliger larvae are still free-swimming and feed on phytoplankton floating in the water. During this stage, the clam’s shell and muscular foot begin to develop, as well as tiny flaps that help the larva swim. This makes the clam get gradually heavier, eventually causing it to sink and settle on the seafloor (this is called the settling stage). It uses its foot to move around until it finds a sandy, silty place to bury itself. The veliger attaches itself to the seafloor by secreting a sticky thread called a byssus. Veligers are only about 0.2 mm (0.0079 in) long (about twice the width of a human hair). The veliger stage can last for several weeks depending on how warm the water is.

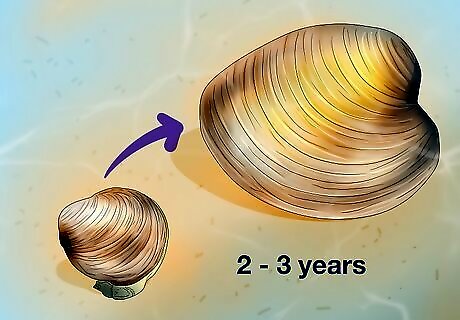

Juvenile clams grow into adults while they’re settled on the seafloor. They bury themselves for protection against birds, crabs, and other predators and eat by extending a long siphon above the mud to filter feed on tiny organisms floating in the water. The tiny clams cannot burrow very far down and are still vulnerable to predators or being moved by wave action. Young clams develop rapidly during the spring, summer, and fall months when the water is warm, but hardly grow at all during the winter. It takes 2 to 3 years for a clam to reach a mature size, depending on the species and climate. Adult clams can dig as deep as 1 ft (30 cm).

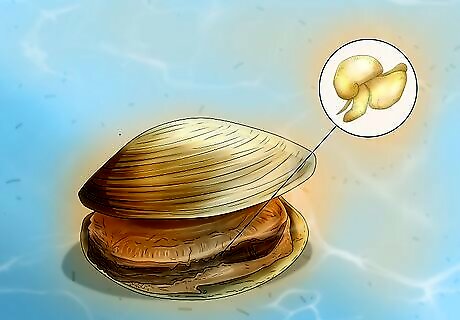

Some clam species raise their young in a marsupium. A marsupium is an internal brood pouch that can hold as many as 20 veliger larvae until they’re more fully grown. Marsupia occur in hermaphroditic clam species that self-fertilize, like fingernail clams. In the case of the fingernail clam, young larvae can stay in the marsupium until they’re nearly a quarter the size of their parent! Clams that develop in a marsupium have a higher chance of survival than clams born from broadcast spawning, but they are born in far fewer numbers. Marsupium-rearing is hard on the parent clam. This is the tradeoff for ensuring their offspring’s survival, unlike broadcast spawners which have no parental responsibility.

Many clams begin adult life as males and transition to females. Juvenile clams need to put a lot of energy into growing and surviving. This means they don’t have the size or metabolic energy to produce egg cells until they’re more grown up (sperm cells are much smaller and easier to produce). By the time most clam species are of a harvestable size, there’s about a 1:1 ratio of males and females. Female clams can produce eggs once they’re about 40 mm (1.6 in) long. It takes about 3 years to reach this size. Since only mature females produce eggs, they’re often fertilized by the sperm of younger males.

Only about 0.00001% of fertilized eggs grow in mature, adult clams. Large clams can release hundreds of millions of reproductive cells during their lifetimes. This is a good thing, since only about 1 out of 1,000 fertilized eggs make it to the juvenile stage of development where they can settle on the seafloor. Of those settlers, only 1 in 100 survives long enough to become an adult. Free-floating and lightly buried clam larvae are incredibly vulnerable to predators and climate conditions, like water temperature. Most clam species live for 10-12 years, with some surviving up to 30 years. The oldest clam ever discovered was a Quahog clam that lived to be 507 years old!

Shell Formation

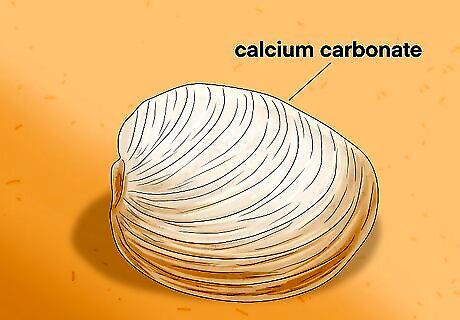

Clams grow their shells by secreting calcium carbonate and proteins. Clam shells (and other sea shells) are not made of living cells. Instead, clams grow their shells from the bottom up by releasing proteins and minerals from their mantle tissue (the tissue that’s in contact with the inside of the shell). To make the shells bigger, clams add more protein and calcium carbonate to the openings and edges of the shell. Clam shells have an outer layer of uncalcified conchiolin (protein and chitin), a calcified, prismatic middle layer, and an inner, pearly layer called a nacre.

Comments

0 comment