views

"Dushman marey tey khushee na karey, sajnaa wee mar janaa,

Deegar tey din gayaa Mohammad, Oorak noon doob jana."

– Saif-ul-Malook

The names of perpetrators and victims keep changing, but the situation remains the same as we continue to regress from one communal riot to another: from Muzaffarnagar (2013) to Asansol (2018).

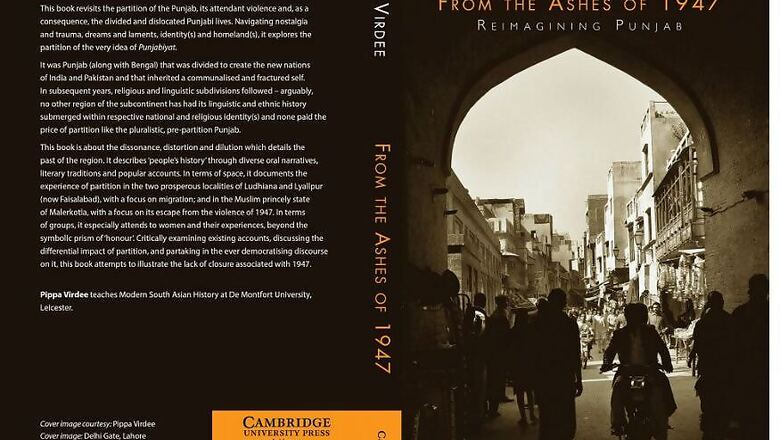

In times of Muslims fearing Hindus and Hindus fearing Muslims, Pippa Virdee’s latest offering “From The Ashes of 1947 – Reimagining Punjab” discloses the ‘details of the blessing of Guru Gobind Singh’ that kept the princely state of Malerkotla safe even at the peak of communal violence witnessed during partition.

When East and West Punjab were trading refugees and dead bodies in the spat of violence and retaliatory violence, Malerkotla, a Muslim dominated princely state, remained protected. The popularly accepted reason for its calmness in times of bloodletting violence is a myth of Guru Gobind Singh’s blessings which the author, who is also a teacher of Modern South Asian History at De Montfort University, Leicester, has captured in her book.

In an attempt to shift attention from the ‘great men’ like Jinnah, Mountbatten, Patel and Nehru to the other important untapped voices during the divisive and fractured times, she conducted interviews and captured on field voices loaded with “sentimentality attached to Guru’s word”.

Post independence, the author continued to experience numerous violent episodes of communal violence, and it was remarkable when she chanced upon Malerkotla that defied the prevailing perception.

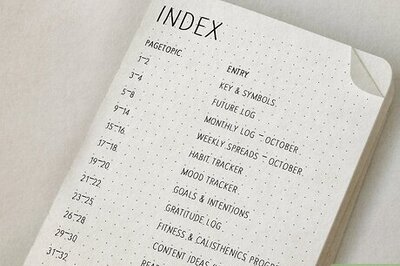

According to the records, the population of Malerkotla in 1941 was distributed fairly evenly between the three religious communities: Muslims were the largest group comprising 38%, Sikhs with 34% and Hindus making up the rest with 27%.

Muslims, however, dominated Malerkotla town. The population of the town in succeeding years was 29,321 with the Muslim community making 76% of the population (Hindus formed 21% and Sikhs formed 1.5%). This trend continued in the post-partition period.

WHY WE NEED TO KNOW MALERKOTLA

During the partition disturbances, Malerkotla saw an influx of Muslim refugees. It was flooded with Muslims, but this trend did not contribute to retaliatory communal violence in Malerkotla. The book captures the time when in an attempt to consolidate Sikh majority areas Muslims were expelled from Alwar and Bharatpur, which Ian Coplan calls ‘ethnic cleansing’, and British CID termed ‘Sikh Plan’ – that sought to carve out a Sikh homeland in central and Eastern Punjab by driving out the Muslims.

By looking at the tensions in neighbouring regions of Malerkotla, the prevalent peace in Malerkotla becomes a case of ‘investigation’ for the author because within Partition Studies little is written about absence of violence in Malerkotla in 1947, “partly because it questions the received histories of the East Punjab Muslims’ sacrifices in the achievement of a Pakistan homeland, and within Sikh East Punjab discourse it is an unfortunate reminder of a different and more tolerant plural history,” the author writes in the book.

She has argued that when we focus on the violent nature of communalised histories both nations – India and Pakistan - stand justified in promoting and maintaining the current stance, which endorses division rather than reconciliation. So with the recognition of cross communal collaboration, the jingoist state discourse faces “challenges and in essence, helps build bridges across international boundaries,” she writes. The accounts of inter-faith dialogues remain peripheral to the wider high politics, which continue to dominate today, as they did then.

THE DETAILS OF THE BLESSING OF GURU GOBIND SINGH

The author, while researching the book, found that Guru Gobind Singh had blessed Malerkotla because the ruler of the princely state protested the execution of his two sons. The story that has travelled for 300 years has also gained mythical proportions and is well known in Punjabi folklore that says that during the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s reign (1658-1707), many battles were fought between the Mughal armies and the Sikhs.

Prior to the onslaught on Chamkaur in 1705 the Mughal authorities captured Guru’s two younger sons and they were asked to accept Islam in exchange for freedom in the court of Nawab Wazir Khan of Sirhind. Guru’s sons refused and were suffocated to death by being bricked in the wall. Fateh Singh was six years old and Zorawar was just over eight when they were executed. At that time the Qazi told Wazir Khan that under Islamic law the two boys were not guilty of any crime and could not be held responsible for their father’s crime.

The Nawab of Malerkotla Sher Mohammad Khan (1672-1712) wrote a letter protesting to Aurangzeb and arguing that this was in violation of Islamic law because the enmity was with their father and not their children. But his protest did not help. However, this appeal came to the notice of Guru Gobind Singh and he blessed the Nawab of Malerkotla saying, “His roots shall remain forever green.”

Since then the succeeding decades witnessed invasions and disturbances in Punjab and a shifting balance of power from the declining Mughal authorities towards the Sikh misls (the twelve sikh armies in the 18th century, each led by a chief, the misls were associated with leading Sikh families who controlled the area), but significantly Malerkotla remained undisturbed by the Sikh forces. The blessing is considered as the most plausible reason, though the author has tapped into other versions of peace behind Malerkotla, which includes its syncretic history and "unsecular mode of governance" as identified by Copland in the Subsidiary Alliance.

Comments

0 comment