views

New Delhi: When Supreme Court on Thursday declined to refer the 1994 Ismail Faruqui verdict to a larger bench, it categorically stated that "law isn't always logical" and that "the facts of the Faruqui case" does not apply to the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi title suit.

The bench has also stated that a "place of particular significance for practicing religion has a different place in law," and that suits would now be determined on the basis of evidence. But can this refusal to refer the Faruqui verdict to a larger bench go against Sunni Waqf Board and other members during the title suit case which is slated to begin from October 29?

Well, even though CJI Misra-led bench has called the 1994 verdict a 'questionable observation', Justice Nazeer has noted that "comment can't be cursorily dismissed". The 1994 ruling had decided the issue of whether namaz or prayers can be offered anywhere — or whether a mosque is an essential part of the practice of Islam and is needed for congregation and to pray.

The SC had then held that Namaz could be offered anywhere and that a mosque was not necessary for this. It also ruled that the government could, therefore, if needed, acquire the land that a mosque is built on.

Now when SC now refused to refer it to a larger bench, it would in essence be used to establish the fact that site of Babri Masjid can indeed be shifted to a different site since “neither namaz in mosque” essential to Islam and state can also acquire such a land.

Dissenting from the verdict, thus, Justice Nazeer had held that this issue indeed needs to be reconsidered by a larger seven judge bench.

This was also the fate that the Muslim parties predicted and that is the reason why the contended that the 1994 verdict was unfair to them and that this decades-old decision played a role in the disputed land in Ayodhya being divided in 2010 into three parts by the Allahabad High Court. To understand the connection between Ayodhya dispute and 1994 Supreme Court verdict, News18 lists down a few questions:

What is the dispute in the title suit case?

The dispute spans across half a millennium, it predates empires – Mughal and British – and now even threatens to disrupt the fabric of modern India.

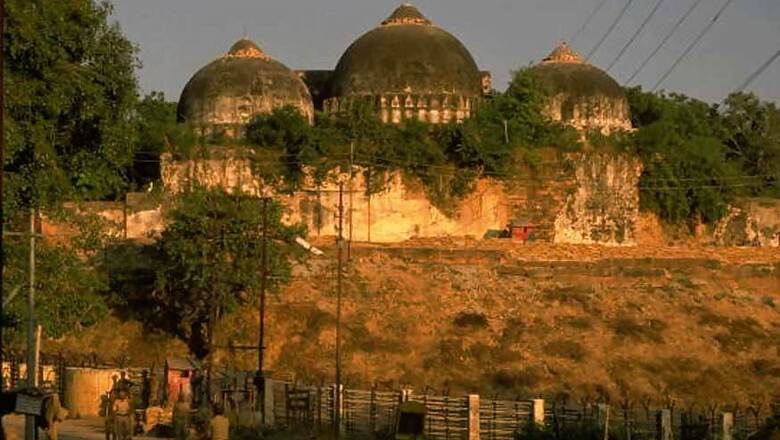

It is about a plot of land measuring 2.77 acres in the city of Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh that houses the Babri mosque and Ram Janmabhoomi. This particular piece of land is considered sacred among Hindus as it is believed to be the birthplace of Lord Ram, one of the most revered deities of the religion. Muslims argue that the land houses the Babri mosque, where they had offered prayers for years before the dispute.

The dispute arises over whether the mosque was built on top of a Ram temple – after demolishing or modifying it in the 16th century. Muslims, on the other hand, say that the mosque is their sacred religious place - built by Mir Baqi in 1528 - and that Hindus desecrated it in 1949, when some people placed idols of Lord Ram inside the mosque, under the cover of darkness.

How did the violence take place and what is the criminal case?

In 1991, the Uttar Pradesh government acquired the land around the structure for the convenience of devotees coming to worship Lord Ram. 1n 1992, the Babri Mosque was demolished by the Kar Sevaks. In 1993, the Centre became the statutory receiver of the disputed 67.7 acres of land under the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Ordinance, 1993 which was subsequently replaced by the Ayodhya Act. The Supreme Court struck down the Ayodhya Act as unconstitutional.

Several political leaders were charged for instigating the Kar Sevak mob to demolish the mosque.

What is the brief court backdrop of the title suit case?

In 2002, hearings began before the Allahabad High Court to determine who has 'title' to the disputed land. On September 30th 2010, a three-judge Division Bench of the Allahabad High Court at Lucknow held that although the site is indeed the birthplace of Ram, all parties are held to be in joint possession of the entire premises in dispute. The Bench ordered a partition of the site equally among the UP Sunni Central Waqf Board, Nirmohi Akhara and Ram Lalla (the deity).

The decision was appealed by the Sunni Waqf Board at the Supreme Court. In May 2011, the Supreme Court stayed the Allahabad High Court judgment. The stay ensured status quo: one priest would continue to worship in the makeshift temple built at the site.

The appeals are now being heard by a three-judge bench comprising CJI Dipak Misra, Justices Ashok Bhushan and Abdul Nazeer.

So, will today's verdict determine who the land belongs to?

No. Today’s verdict will not determine the ownership of the land but determine a key aspect which could impact whether a temple will be built at Ayodhya or not.

The Supreme Court will decide whether to revisit the issue of whether Namaz or prayers can be offered anywhere - or whether a mosque is an essential part of the practice of Islam and is needed for congregation and to pray.

In 1994, the Supreme Court said that Namaz could be offered anywhere and that a mosque was not necessary for this. It also ruled that the government could, therefore, if needed, acquire the land that a mosque is built on.

What is this 1994 Ismail Faruqui verdict about?

In Dr M Ismail Faruqui vs Union of India, the Supreme Court considered the question of acquisition of religious place by the State. It looked at a temple, church or a mosque, etc which were essentially immovable properties and subject to protection under Article 25 and 26.

While offer of prayer or worship is a religious practice, its offering at every location where such prayers can be offered would not be an essential or integral part of such religious practice unless the place has a “particular significance” for that religion so as to form an essential or integral part thereof.

Which means that the SC adjudged that offering Namaz at mosque was not integral to Islam, unless that mosque had any particular significance in Islam.

Who challenged this proposition?

Muslim parties say that this verdict is unfair to them and that this decades-old decision played a role in the disputed land in Ayodhya being divided in 2010 into three parts by the Allahabad High Court: it split the land between Hindu and Muslim parties, though the main part was given to Hindus.

Hindu parties say that by challenging a 1994 verdict on Namaz at this stage, Muslim stakeholders want to delay the main hearing on Ayodhya because they know they are likely to lose the case.

How did the case proceed regarding the challenge to this particular 1994 SC decision?

The Muslim litigants in the Ayodhya dispute case filed for a review of the 1994 judgement after the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad High Court's 2010 verdict ordering that the disputed site be divided into three parts - one for deity (Ramlala Virajmaan), another for Nirmohi Akhara -- a Hindu sect - and third to the original litigant in the case for the Muslims.

When the matter reached Supreme Court, the Muslim litigants demanded that the case should be heard by a larger bench of seven judges as it relates a land belonging to a mosque and thus has implications on the freedom of religion, a fundamental right guaranteed by the Constitution. Currently the case is before three-judge bench headed by Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra.

The Uttar Pradesh government, which is not a party in the title suit, had questioned the Muslim litigants in the Ramjanmabhoomi-Babri Majid title suit case for making "belated efforts" seeking a relook at the 1994 Ismail Farooqui judgment that had said that mosques were not an integral part of religious practice of offering prayers.

The state government had said that the Muslim parties did not question the legality of the 1994 judgement till the appeal against 2010 Allahabad High Court judgment on the ownership of the disputed land was taken up for hearing by the top court.

(With inputs from Supreme Court Observer)

Comments

0 comment