views

One morning, three months after Prime Minister Narendra Modi appeared on television to announce a nationwide lockdown due to Covid-19, I received a screenshot from my father. It was an SMS from his telecom service provider.

He had drained three months of talk-time in two weeks.

A couple of months later, when I could finally make it home to Kolkata from New Delhi, I had mixed emotions after meeting him. Constantly within closed doors, fear of a deadly virus at the age of 58 and absolute uncertainty about the recent future had changed him.

I missed the quiet, reticent man who’d saunter around the house, making sure none of the pipes were leaking, every electric appliance was at its best, the bills were paid at least a week in advance and the fridge was stuffed with food. The textbook definition of a family man.

Now he was either constantly on his phone, talking to his sisters, friends and relatives or arguing with his wife, also my mother, on extremely important subjects like, “but that’s my side of the bed!”

The pandemic has been tough. To capture how men and women, over five-and-a-half decades old, reacted to this once-in-a-lifetime event, four News18 authors narrate their observations about their parents.

‘So close that it almost felt that we were one’

I love telling people that my Ma is a student. I work this bit of information into random conversations to subtly brag about my 65-year-old mother. After retiring from her government job, she enrolled in an art course at Visva Bharati (Shantiniketan) in 2019.

As the middle-aged struggle to deal with Covid-19, for those around them, the wear and tear due to the pandemic was visible. (Shutterstock)

However, as 2020 rolled in with a global pandemic at its toe, my mother’s life as a college-goer – attending exhibitions, watching European art-house cinema – came to a screeching halt. She returned to our home in North Bengal just in time before the series of lockdowns began.

Our home is a 6-room house in constant need of repair. It has an unkempt garden that grows rebelliously in strange ways, much to the chagrin of our gardener. Previously, the house was filled with my father’s songs and shouts (he had anger issues), my grandmother’s uninhibited laughter, and my dog’s lazy woofs. Now, all three of them are dead.

My mother has lived in that house alone for the past one and half years of the Covid-19 pandemic (during which I was stuck in Mumbai as India went from one lockdown to another).

However, she was never lonely (or at least she tried not to be). During the early months of the pandemic, she surprised me with her ability to fill her time with creativity.

Every day, for hours, she sat in our garden doing ‘nature study’. After hearing her talk about this curious exercise for the first few times, I finally asked, “So, you just stare at the plants?” to which she laughed and replied, “No, I pay attention.”

She explained that as an art student, she had been taught to ‘observe’ how a young tendril curls up in shyness and hides behind bigger branches and how flowers open their eyes towards the sun in the morning. She tried to draw these beautiful interactions and developments of the natural world in her sketchbook.

She shared photos of her drawings with me via WhatsApp every day. They were peaceful, almost meditative. However, on some days, the perfectionist in her got the last word. She complained if her ‘alpona’ was not ‘intricate’ enough, or her ‘batik’ colours did not sit well.

For the first few months, all she talked about was art. She learned to use Zoom to attend online classes, learned new words like ‘pdf’ and ‘zip folder’ and asked me to teach her how to make them.

However, sad news soon knocked at her door, as it did on the doors of so many houses during the pandemic. My mother lost her youngest sister — a doctor’s wife, who died for the lack of proper treatment — during the second wave. The first night after my aunt passed away, I stayed on the phone with my mother till it was morning. There wasn’t much to say, but grief and loneliness are not good companions. I couldn’t leave her alone with them.

As Covid entered our homes, we noticed our parents were ageing, the signs of frailty more visible than ever. (Shutterstock)

The week after my aunt’s death also went by in a haze, my mother did not touch her sketchbook. Her osteoporosis had been acting up for some days, but due to the pandemic, she had postponed her treatment. It took a bad turn during this time.

During this period, she talked about all our loved ones who had been long dead. She talked about my father so much that I half expected to catch a tune in his voice in the background every time she called. She talked about her colleagues who left too soon. She lived in the past.

During our video calls, I could see that the wrinkled lines on her face had grown, she had stopped colouring her whites, or combing her hair. Grief changes people, I knew that because I had seen my mother change several times before.

After a couple of months had passed since my aunt’s death, my mother shared a new artwork with me. In the drawing, two vines stood intertwined in each other’s shadows.

I excitedly called her to ask if she had resumed her nature study. She replied that she drew this one from memory. Like the vines, she and her sister too grew up together. “So close that it almost felt that we were one,” she said.

‘Will I lose my value in your eyes if I stop cooking?’

Until a few months ago, my doting mother’s day usually started at 6am and ended by making sure I had my meals. But for the last few months, she doesn’t feel like the mother I once had and it’s frightening.

Earlier, her disciplined lifestyle with 8 glasses of water and 45 minutes of yoga never failed to make us feel inadequate. Her snippets from Reader’s Digest once filled my gallery which now remains empty.

It was not the Covid-19 pandemic that consumed her, it was its longevity. When Covid-19 set foot in India, my mother was awfully sure it would cease to exist in a few months. Even though her Zumba classes shut down, she made sure to make every minute count. I would often be bombarded by pictures of new recipes that she would try until one day all of that stopped.

I was curious. “Will I lose my value in your eyes if I stop cooking?”, she asked.

This was new. She had never cooked out of compulsion, it was her passion, much like reading. Her eyes were tired, I knew it was the Covid-lag overpowering.

She cut down on her reading, cooking and yoga. She would now binge-watch shows, sitting on the sofa, she never did earlier. She would often complain about feeling purposeless. “I don’t even cook anymore, I am becoming very useless for this household,” she said once.

It became worse when she got infected with Covid-19. She had to be put on steroids and that after severely affected her mental health. The social untouchability associated with the disease made her feel lonely as none of her friends came to meet her.

Now, she has completely detached herself from her peers. The once worn-out magazines and digests now lay covered in dust. I do see glimpses of the past in her evening strolls once a week but her dimmed energy makes me worried.

‘He knows the daily Covid-19 figures verbatim’

In pre-Covid times, my father hated me buying hand sanitisers. They weren’t essential then. So every time I’d try to buy a tiny bottle of a scented one he’d remind me, “It’s a waste of money,” because I wasn’t “really going to use it for its intended purpose.”

In the days leading up to the national lockdown, when the hoarding process for the limited quantity of PPE began, I begged my father over the phone to buy a hand sanitiser. He explained the price was hiked, “it was like buying in black.” I argued saying the prices were hiked for a reason and he refused saying he’d wash his hands, which was “100% effective, instead of a sanitizer which was just 99.9%”.

Even though he disagreed, the next day he sent me a blurry WhatsApp photo of a tiny pink bottle of hand sanitiser.

Currently, a shelf at our entryway has a selection of hand sanitizers, disinfectants and more, with my father keeping a careful tally of them, lest they run out before they are replaced.

My father retired in the middle of the pandemic, working all through the first wave, and then after December, suddenly no longer having an office to go to. He worked with numbers, first at Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation, and after retiring, freelancing for auditing firms. During the second wave’s regional lockdowns which kept us indoors, he developed an obsession with a different kind of numbers: daily new Covid-19 cases.

It started with telling me the numbers in a grim tone every morning. “There are over 3,000 cases in the city now.” I had stopped looking at the numbers, but my father knew them, morbidly. How many people died today, how many of them were in the city, and how many overall in the country. Sometimes it wasn’t the exact digit, but you could tell he’d looked up the daily tally.

The thought of staying home was unbearable, more so for the middle-aged who had found peace in a regular routine. (Shutterstock)

At times, I’d overheard him mention the numbers to others — to the people who came by in person. He’d chide them for not wearing a mask, then add a statistic to back it up: “2,000 cases today. Covid is no joke.” In his free time, he would have long phone calls spanning for hours with family I only vaguely remembered — aunts, uncles and his old friends. He discussed everything a newly retired person trying to adjust to a global pandemic would. How he was not going out unless essential, how the finance market was doing, where he planned on investing, politics, the weather and finally, the grim sentence of “cases are increasing again,” followed by the daily number.

Even months after the second wave has subsided and I’d be leaving the house, I’d instinctively ask, “Cases are still on a downward trend?” He still knows the daily number.

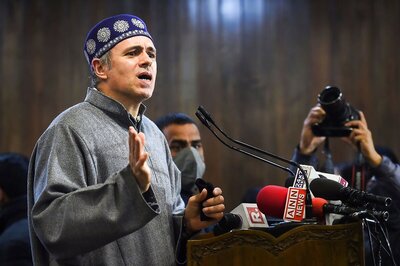

‘Finding peace in religion’

One morning in March 2020, my father realized that the future is going to be tough. “Ab kya hoga” (What will happen now), he raised the concern. His worry was not individual, it was communal.

He had turned 55 and the thought of staying home was unbearable for him.

Till a few days before the viral catastrophe, life for him revolved in repetitive circles. Waking up, taking a quick walk outdoor, doing the usual chores, going out for work and then coming back. But the freedom of staying outdoor was never realized until the call for communal confinement came.

The new life made everyone uneasy to different limits, but for my father, it was confinement, more mental than physical. Unlike our generation whose criteria for survival are roti, kapra and mobile phone; people of my father’s age still prefer social groups over Facebook.

As the lockdown began, it was tough to keep us (as a family) entertained. My siblings and I would spend hours on our smartphones, but for my father sources to keep him engrossed exhausted. Television lost its taste, board games became obsolete and books were uninteresting. For my mother, things were pleasant as all the three children, (two had to migrate for study) were home.

So we devised an escape route. We started talking to him more and more. Since there was hardly anything to do except eat and sleep, we talked about everything under the sun. But the plan also led to arguments.

But with every calamity, comes a coping mechanism. Religion came to my father’s rescue. He turned his isolation into spiritual meditation.

Rounak Kumar Gunjan also contributed to this story.

This story is the last article of a 4-Part series on Pandemic Fallout. Click here to read Part 1 on Covid-19 and its toll on mental health; here for Part 2 on on how Covid has changed career paths and here for Part 3 on faith as ray of hope amid Covid.

Read all the Latest News , Breaking News and IPL 2022 Live Updates here.

Comments

0 comment