views

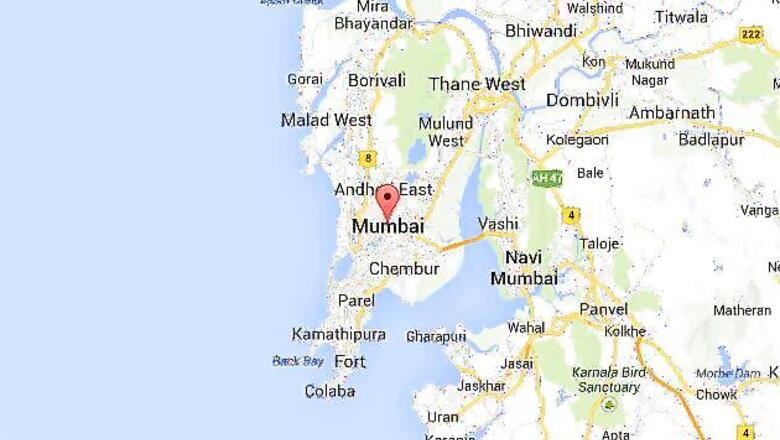

When the Bandra-Worli Sealink was finally opened to traffic on June 30, 2009, the media went into overdrive suggesting that the bridge over the creek separating north and south Mumbai was a symbol of new possibilities. Inaugurated after tens of thousands of residents witnessed a spectacular laser show and fireworks display, the Rs 1,600-crore project was hailed as "another jewel in Mumbai's crown", an "engineering marvel", even "a fairy-tale structure created by the God in heaven". Ajit Gulabchand, the head of Hindustan Construction Company, which had been contracted to build the bridge, declared that the Sealink was "truly...a monument to human skills, enterprise and determination".

In 1845, similar excitement had greeted the inauguration of a bridge about a kilometre away from the Sealink. "...An immense concourse of every race and kindred, shade and hue" assembled to watch Bombay's governor declare open the Mahim Causeway, reported The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce. Music by military bands and a thundering gun salute rent the air. Like the Sealink, the Mahim Causeway, which is still in use a century-and-a-half later, is a testimony to human skill and determination. More significantly, though, it is a monument to a magnificent, sadly fading Mumbai tradition: Mind-bogglingly munificent support for public works. Funds for the project, which cost Rs 1.6 lakh (the equivalent of £17,000 at the time) had been donated by Lady Avabai Jejeebhoy, wife of the merchant Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy.

Until the Causeway was constructed, travel between Bandra and Mahim involved a boat journey, a trip that was especially precarious during the choppy monsoon. Lady Jejeebhoy was moved to loosen her purse strings after two especially fierce storms in 1841 caused 15 or 20 boats to capsize, claiming several lives. As in the case of the Sealink, the Causeway experienced significant cost overruns. The project was initially estimated to cost Rs 67,000, but Lady Jejeebhoy greeted each revision with generosity. Recounting the donor's reaction to the escalation, Governor George Arthur said, "Lady Jamsetjee had frequently urged that, as the poorer classes of the community were concerned, it is no more than right and just that the rich should contribute to their wants."

That radical notion, that the prosperous had a responsibility for the welfare of their less-fortunate neighbours, is what made Mumbai different from other Indian cities in the 19th century. In the rest of the subcontinent, charity was directed mainly towards religious and community activities. But Mumbai's newly-minted millionaires, many of whom had made their fortunes selling cotton and opium to China, collaborated enthusiastically with the colonial administration to fund infrastructure and institutions for all residents, irrespective of caste or sectarian affiliation. They financed public hospitals and the new university, libraries and schools, drinking-water fountains and animal shelters. This made Mumbai, the urbanist Preeti Chopra has noted, a genuine "joint enterprise", shaped as much by Indian aspirations as by the imperatives of colonialism.

The most notable of these philanthropists was Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, a Parsi orphan from Navsari who moved to Mumbai to join his uncle, a bottle seller. Seizing the opportunities offered by the port-city and demonstrating an iron stomach for risk-taking, Bottlewaller-as he sometimes signed his letters-flourished in the China Trade. He eventually formed an alliance with the Scottish trader William Jardine. His acts of charity grew in lockstep with his prosperity. His first public philanthropic gesture came in 1822, when he spent Rs 3,000 to release men who had been jailed for failing to pay their debts.

By 1848, three years after the inauguration of the Mahim Causeway, Jejeebhoy had bequeathed £250,000 on public causes. By the time he died in 1859, he had made bequests to 126 public charities, the most visible of them being the two enormous Mumbai institutions that bear his name: The Sir JJ School of Art and the JJ Hospital. His benevolence is still revered. On his birthday on July 15, dozens of grateful Mumbai residents still offer coconuts and marigold garlands to the black statue of him that presides over a hallway in the JJ Hospital.

The generosity of the Jejeebhoy family was rivalled only by that of the Baghdadi Jewish Sassoon family, whose name also adorns a variety of establishments in Mumbai and Pune. The patriarch David Sassoon arrived in Mumbai in 1832, fleeing religious persecution at home in Baghdad. He began to export cotton to Persia.

He soon expanded into building wharfs and establishing a trade network that covered East Africa, Afghanistan and China. He and his sons also opened cotton textile mills, the engine of Mumbai's economic growth, and, like the Jejeebhoys, made donations to public projects of all descriptions. These include the David Sassoon Library, the Jacob Sassoon School and the monument that stands at the heart of Mumbai's business district, Flora Fountain, named for David Sassoon's daughter-in-law.

David Sassoon

It wasn't just Jewish and Parsi families who opened their purses. The diversity of the caste and religious groups from which Mumbai's philanthropists were drawn can best be observed from reading the names on the marble plaques of pyaus-drinking-water fountains and troughs for humans and cattle-that still dot older parts of Mumbai: Indira Sahasrabuddhe, Khimji Mulji Randeria, MV Parulkar, Kessowji Naik, Husseub Karmali, Anand Vital Koli.

After building 40 fountains in Mumbai, one generous city merchant, Cowasji Jehangir "Readymoney", even donated funds for one to be built in London's Regents Park. When the structure was completed in 1869, he merited mention in the humour magazine, Punch. It noted that "Parsi money was better far than parsimony." (His family would go on to fund the Convocation Hall at the Mumbai University, the Cowasji Jehangir Hall that now serves as the National Gallery for Modern Art, and the Jehangir Art Gallery.)

In the 20th century, the Tatas emerged as the city's-and India's-most generous business house. Just under 66 per cent of the group's profits go to charity. The Godrejs also fund programmes such as a mangrove reserve, a centre for Scouts, and the World Wide Fund for Nature.

But even as the number of wealthy residents has burgeoned, philanthropy seems to be a fading tradition in the city that once prized it as a prime virtue.

Though Mumbai is now home to nine of the 15 richest Indians and has the world's seventh-highest concentration of high-net-worth individuals, they now seek 'public-private partnerships' that will bolster their profits, instead of viewing charity as a social obligation to the less fortunate. Little wonder, then, that Mumbai's once-prized bridges between social classes seem to be crumbling.

Comments

0 comment