views

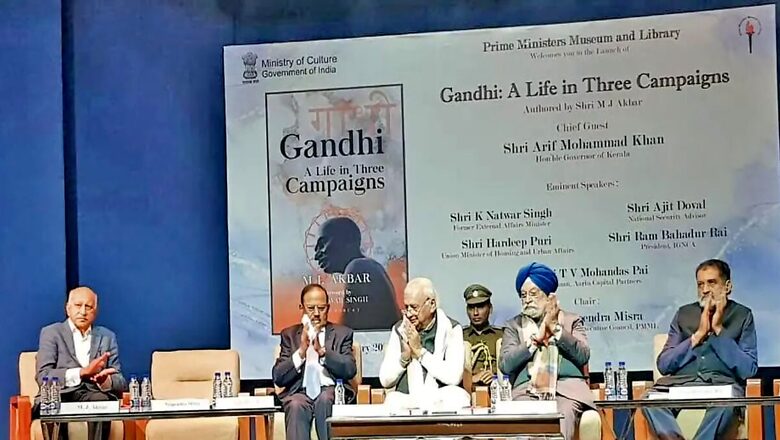

Mahatma Gandhi is one of the most discussed personalities of the 20th century, and numerous volumes of biographies have been dedicated to him. Despite literature overflowing on Gandhi’s life, persona, actions, and philosophy, few biographers have been able to capture a holistic sketch of the enigma called Gandhi. Gandhi’s life is an invitation to explore the paraphernalia of Indian political thought, by acquainting oneself with layers upon layers of Gandhian philosophy and praxis. The latest book of MJ Akbar, a devout student of Gandhi and a sincere historian of modern India, distinctively titled Gandhi: A Life in Three Campaigns, is a praiseworthy attempt to resurrect and contemporise the legend of Gandhi for present times. Yet another biography of Mahatma Gandhi, which may be regarded by some as just a brick in the mansion of Gandhian lores, is nevertheless a very valuable contribution, because each biography of the man is an act of reinventing Gandhi.

As implied in the title itself, the book recreates the life of Gandhi through three of the most significant political campaigns he designed and organised against British rule — the Non-Cooperation Movement of 1920, the Salt Satyagraha/Civil Disobedience Movement of 1930, and the 1942 Quit India Movement. Stitching the chronicles of the three campaigns together, Akbar has authored a lucid and comprehensive biography, touching upon all the personal and political dimensions of the Mahatma.

The book begins with an analysis of Gandhi’s political philosophy, its pillars, and his knack for developing a political lexicon of his own, which would soon resonate with the Indian masses. Before the launching of his first major political campaign, the Mahatma was adequately thorough with the praxis of his foundational ideas, as embedded in his political manifesto ‘Hind Swaraj’.

As described in the book, spinning, non-violence and non-cooperation formed the three ‘pillars’ of Gandhian political ‘doctrine’. Khadi, for Gandhi, was the thread which would adorn India with the hand-woven fabric of swaraj. He saw in khadi the promise of self-reliance, economic empowerment, upliftment from poverty, and the attainment of swaraj. He referred to khadi as “the thread of destiny”, and “transformed khadi from the compulsion of poverty to the dress code of nationalism”. Interestingly, for Gandhi, the thread of India’s destiny lay with the women, and so did India’s economic independence and quest for swaraj.

Gandhi was well aware of the global political developments, and he fine-tuned the declaration of the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1920 with the launch of the Khilafat Movement, with the belief that it would help orchestrate the freedom struggle through a consolidated Hindu-Muslim unity in action. The coinage ‘non-cooperation’ was dedicated to the emerging political lexicon of the Indian freedom struggle, and as beautifully put by Akbar, “this coin would deflate the currency of colonialism”. Gandhi laid out the pillars of swaraj — “non-violence, Hindu-Muslim-Sikh-Parsi-Christian-Jew unity, total removal of untouchability and manufacture of handspun and handwoven khaddar completely displacing foreign cloth”.

On August 14, 1921, Gandhi noted: “Swaraj is the abandonment of the fear of death. A nation which allows itself to be influenced by the fear of death cannot attain swaraj, and cannot retain it if somehow attained.” He understood that the psyche of the Indian common masses had been suppressed through a reign of fear and terror, and that its unshackling from fear of the imperial power was the only way to usher in swaraj.

As Gandhi saw it, the British had colonised Indian minds through both fear and display of power, and had unleashed what he labelled an ‘unsexing process’, by exercising physical and psychological repression. He was well aware that the British intended to retain their global power by shaping their colonial subjects in their image, and by placing their ‘puppets’ in positions of power in the colonies. As pointed out by Akbar, Gandhi termed this neo-colonisation by the British as a “double crime”. Gandhi devised an apt response to this British attitude — non-violence as a voluntary choice over violence (and thus a greater proof of valour), and the idea of “Kshama Veerasya Bhushanam”, i.e., forgiveness as a virtue of valour.

Political independence, for Gandhi, would just be the beginning of swaraj. Attaining political independence was inevitable once the Indian mind and life could be decolonised. He structured his campaigns in a manner that gave him the confidence to declare that India could have swaraj within a year, if the pillars of swaraj were dutifully established.

As he put it: “Swaraj means a state such that we can maintain our separate existence without the presence of the British… The problem is no doubt stupendous even as it is for the fabled lion who, having been brought up in the company of goats, found it impossible to feel that he was a lion. As Tolstoy used to put it, mankind often laboured under hypnotism.”

Akbar argues that after taking over the reins of the Congress, Gandhi facilitated a kind of decolonisation process for the Congress party, its structure and mode of functioning. He ushered in a fundamental transformation of the party, by loosening the grip of professional elites such as lawyers and converting it into a mass movement, and advocated the ‘non-possession’ of wealth so that elites would have to ground themselves and work in tandem with the impoverished masses. Although the Non-Cooperation Movement was able to mobilise the common Indians like never before, Gandhi called it off after the Chauri Chaura incident, a move much criticised then as it is now on public forums. Nevertheless, the movement had made its impact, leading to the repeal of the Rowlatt Act.

Given that the Khilafat Movement had also gained steam due to its coupling with Non-Cooperation, the former also couldn’t keep up its pace and wasn’t able to bring about communal amity as it was envisioned to do. According to Subhas Chandra Bose (and Akbar’s approval of his assessment), this was due to “allowing the Khilafat Committee to be set up as an independent organisation throughout the country, quite apart from the Indian National Congress”, which meant that the mass support for the movement couldn’t be integrated into the national movement and didn’t metamorphose into support for the Indian National Congress. According to Akbar, Gandhi faulted in his belief that “idealism and charisma could woo hard-line Muslim leaders invested in religious ideology into his embrace”, an error which would prove too costly for the nation to bear.

Akbar beautifully brings out the portrayal of Gandhi as a master communicator. A frail saint sure-footed in his principles, the Mahatma’s convincing powers could stir the souls of even the staunchest of the British Empire’s supporters. The confidence that Gandhi exuded could only be gauged by the availability of eccentricity that he displayed while in dialogue with the representatives of the empire. For instance, while on trial before Justice Broomfield, he pleaded guilty for all the charges, as “non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as is cooperation with good”, and suggested the judge “either to resign your post, or inflict on me the severest penalty”.

Similarly, in 1927, when Gandhi had a conversation with Lord Irwin about the review of the colonial constitution, he began persuading the latter to wear khadi. Gandhi, on the persuasion of his acquaintances, could write a letter to Hitler, requesting him to stop the inhuman persecution of Jews, ending his letter with the statement, “Anyway, I anticipate your forgiveness, if I have erred in writing to you.” On being questioned about his khadi loincloth at King George’s reception in London as it supposedly didn’t adhere to the prescribed dress code, Gandhi retorted to the journalists, “The King had enough (clothes) on for both of us.” He was a prolific writer, literally addressing every subject possible, ranging from giving advice on how to tackle the menace of monkeys in urban localities, addressing the issue of “old men marrying young girls”, to advising child widows and those seeking knowledge about naturopathy. Swaraj, of course, was never out of his thoughts and actions. In 1931, he had declared before the Congress, “If swaraj cannot be had without a Mahatma, then, believe me, you will never be able to rule yourselves.”

Being a keen observer, Gandhi had anticipated the uprooting of culture that English would bring about in India through a colonisation of language and communication. In an oft-quoted letter to Tagore (also quoted by Akbar) the Mahatma explained his idea of culture which is worth reproducing here in toto: “I know families in which English is being made the mother tongue. Hundreds of youths believe that without a knowledge of English freedom for India is practically impossible. The canker has so eaten into the society that, in many cases, the only meaning of Education is a knowledge of English. All these are for me signs of slavery and degradation… I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any. I refuse to live in other people’s houses as an interloper, a beggar or a slave…”

Gandhi always strived to have his fingers on the pulse of the nation. He travelled intensely before initiating any mass movement, to rejuvenate the spirits of the masses and replenish his political armoury with young leaders and innovative ideas to challenge the British Raj. During his travels, he focused on social reforms and addressing local issues while conveying his political message. Perhaps a Gandhian travelogue is in order, awaiting its compiler-cum-author.

As Akbar articulates the impact and essence of Gandhi’s tours spanning the landscape of India: “Gandhi travelled by train or bullock cart from one end of India to the other, berating Indians for social evils such as untouchability and child marriage and urging the millions to spin khadi. Gandhi was saviour of the impoverished, initiating a cathartic resurrection that included improved sanitation, better health, cattle farms and prohibition. India was dying, he said, and the spinning wheel was the cure. Gandhi was back among those to whom he belonged. Scenes of loving homage were replicated wherever he travelled. Such an imperishable and invincible bond of faith has few parallels in the timeless narrative of humankind.”

Gandhi was one the rare political leaders of the 20th century, who had successfully groomed a whole generation of leaders who would lead India to its freedom and shape the journey of independent India. Jawaharlal Nehru, being his political heir, was the most prominent among them. In his biography of Gandhi, Akbar highlights that ideological disagreements had started developing between the two early on since 1928. Being influenced by European socialist ideals, Nehru was sceptical of Gandhi’s critique of Western civilisation and his exaltation of Ramrajya as an ideal to be cherished. Despite the differences, Gandhi crowned Nehru his political heir in 1929 itself by placing him as the president of Congress for the Lahore session, endorsing his democratic credentials and stating that, “Nehru’s being in the chair is as good as my being in it. We may have intellectual differences but our hearts are one.” Nehru’s anointment sealed the fate of independent India, and history is the best judge of his democratic credentials. In any case, Akbar’s biography persuasively implies that the ‘intellectual gap’ between the two only widened with time.

During his visit to London to attend the second-round table conference regarding the structure of the Indian government, Gandhi gave a glimpse into his idea of governing a free India during an interview, as cited by Akbar: “You ask me how I would fulfil my dreams if I had the power, what I would do to wake the ‘dumb, starving millions’ from their lethargy, make them articulate, and give them food. I would make them work. At what? At the charkha and handlooms. I would educate them. Yes, on Indian lines. I would build new roads – fine roads that would benefit both man and beast. I picture the new India as filled with linked villages, happy in their industries… I should love to go back (to the ashram), but I should not hesitate to shoulder the burden of leadership if it came to me.”

Akbar’s book provides very deep insights into some seldom discussed aspects of colonial India’s political trajectory — Gandhi, Ambedkar and the depressed classes. Gandhi had devoted his entire life to the eradication of untouchability, and was staunchly against caste discrimination. By entering into the Poona Pact of 1932, he ensured that Ambedkar’s advocacy for separate electorates, which Gandhi considered a “modern manufacture of a Satanic government”, didn’t convert into a reality. Gandhi realised his own contributions and publicly articulated the immense work he had done for the Depressed Classes.

The Poona Pact prevented a bloody vivisection of the Hindu society and brought about a radical transformation which began with throwing open thousands of Hindu temples to the Depressed Classes. At the same time, Gandhi also understood the dire consequences of endorsing permanent reservations and was critical of entertaining the idea. As Akbar notes, the significance of Gandhi’s contribution to their upliftment can be sensed from a statement by P Baloo, a leader of the Depressed Classes: “Your life is a greater guarantee to the Depressed Classes than any number of Constitutions.”

Akbar’s biographical sketch of the Mahatma unravels the life of Gandhi holistically — delving into both the personal and political life of the man — and appreciates his strengths while critiquing his weaknesses. It brings out Gandhi as a classic negotiator, a master strategist, and an astute politician who never lost his sense of playfulness even in the hardest of times. So much so, that even when negotiating with MA Jinnah, Gandhi could irritate the stubborn hardliner by requesting to reply in Urdu, very well aware that the father of Pakistan did not know Urdu.

Gandhi was the locus of power for several decades, but he remained away from power throughout his life while always flirting with it, and centring the architecture of anti-colonial power around himself. He had a unique persona which could create mass movements on the issue of salt tax and could dream of swaraj when even the topmost leaders of Congress were not able to challenge the moral foundations of the British Raj.

He countered the idea of divide and rule with his slogan of ‘Do or Die’, and was ready to leave India to anarchy rather than have the Indian nation reeling under the burden of imperialism. Gandhi’s walk through the communal fire of Noakhali is an archetype of abandoning the fear of death and healing the psychological wounds of an impending partition.

It’s interesting to note that in a way, most of the mass movements initiated by Gandhi which led to India’s independence, had an anti-climactic ending. The same may be true of Gandhi’s life as well. Yet the Mahatma gave India the hope of having swaraj, surajya and Ramrajya.

Akbar’s book is a fitting tribute to the life and message of Mahatma Gandhi.

Yashowardhan Tiwari is a Research Fellow at India Foundation. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment