views

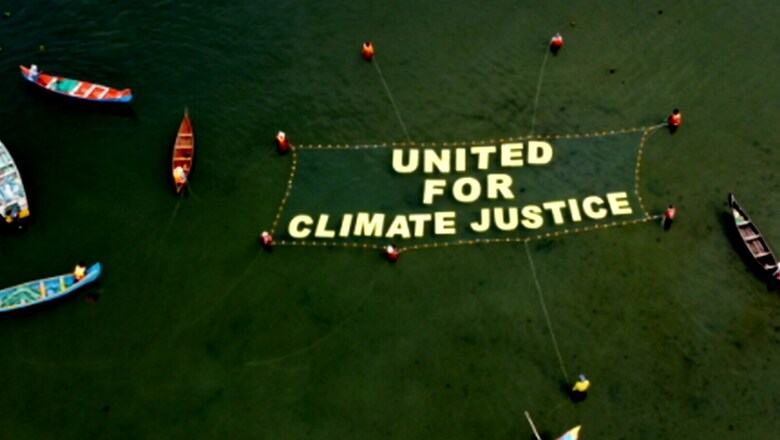

In 1991, on behalf of the Alliance of Small Island States (AISOS), the island country Vanuatu brought up ‘loss and damage’ compensation as a key climate demand. More than 30 years later, we are yet to see any concrete steps to acknowledge and act on loss and damage globally. This is probably best reflected in the documentation of loss and damage itself. The United Nations (UN) defines it as the largely irreversible economic and non-economic losses suffered by vulnerable countries due to climate change impacts. In principle, loss and damage also include the damage to cultural heritage, history and identity, indigenous knowledge and local ecology. However, the climate crisis has cascaded over the years and today, countries in the global south such as India face compounding impacts that are far beyond direct post-disaster losses and last generations.

COP27, being held at Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt this year, is being hailed as the year for loss and damage, in hopes of it throwing light on the growing climate crisis in the global south. Such discussions in recent times have leaned towards developing countries asking the developed to financially compensate for these damages. In the global south, it is becoming more apparent that communities face increasing risks of climate crisis losses due to the inability of world leaders to limit greenhouse gas emissions in a timely, efficient and just manner.

This year, 130 developing nations together had ‘loss and damage’ added to the agenda for the first time. It echoes the 2009 negotiation, where developed nations historically agreed to provide $100 billion per year to developing countries as ‘climate finance’. This seems fair since developed countries have been the largest contributors to global warming and climate change. Nearly 92% more emissions than countries in the global south. At COP27, a few of these nations, including USA, Germany and Austria, have pledged little amounts to developing countries. Although some progress, this is far from the original commitment and the process comes with its own vices. We have seen during climate disasters even in 2022, that those who have pledged money have done so as ‘loans’, pushing struggling countries into debt. On the contrary, the original proposal had clearly mentioned that funds for loss and damage must be separate from any other existing multilateral financial flow. Alongside this, it is pertinent to note that the climate funds that do come in are directed towards mitigation and adaptation plans.

Even within this, according to the OECD, of the total mobilised finance of USD 83.3 billion in 2020, USD 48.6 billion (58%) was routed to mitigation, USD 28.6 billion (34%) to adaptation and USD 6 billion (7%) for cross-cutting activities. In reality, more than 50% of climate finance must be utilised for adaptation measures, with this commitment being doubled by 2025.

However, loss and damage itself refers to impacts that occur beyond what mitigation and adaptation measures can take care of. In recent documentation, the IPCC acknowledged that depending on mitigation and adaptation measures for climate actions is no longer effective. Especially in the global south, not only is loss and damage already becoming unavoidable but the cascading nature of impacts is moving towards irreversibility. The finance required for climate impacts in the global south once a disaster occurs is rarely accounted for.

Still recovering from multiple climate losses since COP26, India has made its intention to focus on loss and damage this year clear. The Union Environment Minister even stressed that the country does not recognise loans as climate finance and will push for definitive climate grants in COP27 negotiations. However, at a national level, the country still lacks implementation of the principles of loss and damage in its climate efforts. In the current budget year, the central government has allocated only Rs 60 crore to the national adaptation fund, against the startling USD 159 billion (15.9k crores) in losses incurred just due to extreme heat, 5.4% of India’s GDP. Most apparent is the striking need for the most climate-vulnerable communities in the country to be heard and supported.

As an example, India began using the post-disaster needs assessment tool following the 2018 floods in Kerala. While the tool helps estimate economic loss and the resulting compensation, it lacks the robustness necessary for the current state of the climate crisis in the country. Not only is it mostly used for floods, despite the growing heatwaves, pollution, and drought, but it also fails to account for the sheer inequality of climate impacts across India’s diverse population.

Recent reports state that climate migrants in India have been steadily increasing each year, standing at 4.9 million in 2021. One of the key factors contributing to rising climate migrations is the fundamentally inadequate finance for adaptation measures. A majority of these migrants belong to farming, fishing and labourer families, indicating that communities directly dependent on the environment are worse affected. Further magnified, within these communities, gender, caste and socioeconomic inequities mean that some people are further disadvantaged with minimal access to solutions. In many climate-vulnerable regions like Sundarbans, there have also been reports of girls being taken out of school and forced into child marriage in the aftermath of destructive cyclones. These intangible impacts, driven by the diversity and inequity among our population last across generations and are not accounted for in mitigation, adaptation and post-disaster measures. Adequate climate adaptation funds can help generate livelihoods and ensure access to housing, education and medical facilities, resulting in improved resilience which can reduce climate-related migrations in India.

As India takes the stage at COP27 being one of very few countries moving towards achieving climate targets and proposing updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), our representatives have stressed on the importance of climate finance for loss and damage in developing nations. In these discussions, we must remember to acknowledge the inequalities of climate impact in the country and the crucial role that communities and community-led climate resilience play in effective climate action and justice measures. India’s geographic and social diversity requires localised, contextual approaches to climate adaptation if the country aims to achieve the NDCs in a just and equitable manner. Having dialogues with the most impacted and routing climate finance to these regions and communities with clear steps for monitoring and evaluation is the need of the hour.

Meanwhile, India has also pushed for a deal phasing out “all fossil fuels”, raising questions about such a deal minimising focus on the country’s heavy dependency on coal. While phasing out oil and gas is crucial to global climate action, this must not halt India’s attempts at just transitioning away from coal. This is a perfect example of the dual responsibility India holds in demanding global action while continuing national efforts towards climate action and justice efficiently.

World leaders at COP27 need to address and acknowledge the growing gap in climate finance and swiftly implement effective compensatory measures. For countries like India, with the number of hazardous disasters and resulting impacts increasing each year, accounting for loss and damage is crucial for our climate fight. Closer to home, India has shown its strength in taking tangible steps towards climate mitigation in the country, but there is a crucial need to do more on the adaptation front. By including socially just measures and bringing climate-vulnerable communities to the discussion, we stand the chance to truly lead the way to climate justice worldwide.

Avinash Chanchal is the Campaign Manager of Greenpeace India and has played a pivotal role in the organisation’s work focussed on sustainable mobility, air pollution, renewable energy and climate adaptation. Tamanna Sengupta is part of the communications team at Greenpeace India, assisting with campaign research and digital communication strategies. Her research experience includes biodiversity conservation, policy and extreme weather. She is an active member of youth climate movements in India. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment