views

A stray remark by my young Bihari driver in Kolkata added a new dimension to the issue of the Gyanvapi mosque in Varanasi, for me. Only, he was talking about Ayodhya, not Kashi. Voicing his intention to visit Ayodhya with some of his friends as soon as the rush wanes a bit, he was surprised to learn from me that there used to be a Mughal-era masjid on the spot where the new grand Ram Mandir now beckons a wide range of devout Indians.

What followed, obviously, was a potted history of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, which he listened to with a mixture of concern and amazement. Why was a mosque built where Sri Ramji was born, he asked, clearly unaware of the tumultuous events of the early 16th century, much less the last decade of the 20th century. Born in the 1990s, he was also bemused by the fact that there could be any resistance to a Ram temple being built there again.

But at least he—his friends’ motivations and emotions are unknown—does not seem to harbour any animus towards those who had thwarted the rebuilding of a temple, through the courts and otherwise. That is probably because the medieval-era mosque at that site did not retain any architectural remnants—spolia—of any older preceding structure, so there was no immediate recall or incontrovertible proof of what had been there. What will he make of Gyanvapi?

For decades a tiny but influential minority of ‘historians’ have tried to paper over the grim truth of the oddly named Gyanvapi masjid, denying evidence in Maasir-i-Alamgiri, written by Saqi Mustaid Khan, of Aurangzeb ordering the destruction of the Vishwanath temple and the building of the extant mosque. These historians even cancelled the brilliant Sir Jadunath Sarkar for highlighting Aurangzeb’s zealotry, calling the Bengali historian communal instead!

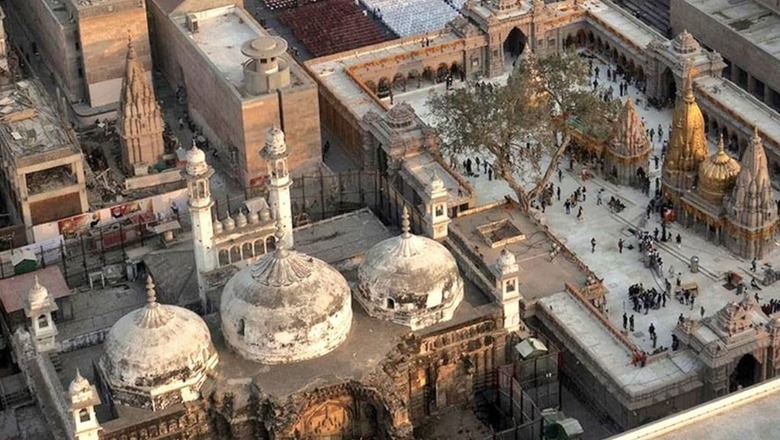

Had the temple been entirely destroyed (like the one in Ayodhya) the fiction that Gyanvapi was not an act of communal vandalism could have been maintained. But Aurangzeb’s decision to retain an entire wall of Kashi’s most prominent temple in the design of a new mosque that would sit on the plinth of the razed Hindu place of worship, however, reveals that he wanted the Hindus to feel the pain of that demolition for centuries and generations to come.

The temple was the target of earlier Muslim rulers too, with the first demolition ordered by the Ghurid conqueror Qutubuddin Aibak in the 12th century. It was rebuilt a few decades later, away from the original site, only to be destroyed again in the late 15th century in Sikandar Lodi’s reign. Akbar’s Rajput generals, Raja Man Singh and Raja Todar Mal rebuilt it yet again in the late 16th century only for Aurangzeb to zealously decree its final humiliation in 1669.

When the Marathas gained control of Kashi in the 18th century, the holy city’s remaining temples got another lease on life, the ghats were refurbished and an abode for Lord Vishwanath was built anew by Maharani Ahilyabai Holkar on an adjacent site as the Nawab of Awadh thwarted any reversion of the Gyanvapi mosque. But, poignantly, the statue of the faithful Nandi bull looks steadfastly in the direction of the destroyed temple. In anticipation.

Now the report of the Archaeological Survey of India has revealed the extent of what happened to the temple—whether of Vishweshwar or Avimukteswar or any other Hindu deity—where Gyanvapi mosque stands today. Not only was the entire Hindu structure demolished except for the western wall, its spolia (debris) were reused in the mosque. That is not surprising, as the first mosque built in India, in Mehrauli, also used temple spolia—and declared it.

The ASI report says its recent survey of the Gyanvapi premises revealed 34 inscriptions on spolia used in the mosque commissioned by Aurangzeb, in Devanagari, Grantha, Telugu and Kannada, and that they mention deities such as Rudra, Uměśvara and Janardhana. It also claims that sculptures of Hindu deities and carved architectural members were found buried under the soil in a cellar inside the compound. The implications are quite apparent.

It is clear that there was a Hindu temple on that spot before the mosque, even if some people refuse to acknowledge the one intact wall—complete with Hindu imagery and motifs—as evidence of its existence. It is also clear that the temple was demolished (barring that wall) to make way for a mosque, which was built on the existing plinth. And it is clear that the rest of the rubble left from the demolition was used in various parts of that mosque as well.

The discovery of spolia with south Indian epigraphs including in a script specially developed to write Sanskrit—Grantha—also belies current assertions that the southern part of the subcontinent had little or no ties with the north. Though the inscriptions are yet to be translated, they perhaps note donations to the temple that stood there by pilgrims and notables from the south. Thus, it was an important temple; so the retention of one wall was doubly significant.

Keeping that wall intact served as a reminder to the majority community about its position in an empire ruled by the minority: beaten and subjugated. And this incongruity was made possible by the inability of the majority community to realise its common plight, divided as it was by caste and regional loyalties, which were assiduously played up and perpetuated by different vested interests for centuries. It was also a warning to stay down and be quiet.

Aurangzeb’s act was both supremely arrogant and very foolish. He evidently did not feel the need to hide his iron hand in a velvet glove unlike many of his forebears. He wanted to rub the Hindus’ noses in the dirt—even though they made up roughly 85 per cent of his subjects—secure in the belief that they would never do anything about it. That the Gyanvapi mosque with its temple wall still stands 350 years later, is a resounding vindication of his belief.

But Aurangzeb was also foolish—to think that the tide would never turn. Brazenly leaving evidence in Varanasi has made it tough for his defenders today to deny his true bigoted motivation, as excavations at Kashi and many other places reveal the extent of the destruction. Incidentally, the Rudra Mahalaya temple at Patan also has a mosque built amid the visible remnants of a temple. Only, the whole site is ASI-protected and hence there is no tussle about worship.

Even if the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991 pushed through by the Congress government freezes their status as they existed on August 15, 1947, prohibiting the reversion—some call it ‘liberation’—of the temple at Kashi (and other places), the mountain of evidence pointing to deliberate destruction of temples to erect mosques needs discussion, not denial. Only then can inter-community relationships—not just places of worship—be rebuilt.

Meanwhile, a new generation of Indians visiting the grand, new Ram Mandir at Ayodhya—like my driver—will inevitably learn about what preceded its construction. And also, what the current situation is at Kashi and Mathura, even if thousands of similar desecrations of the past centuries remain sequestered from public consciousness. The role of the courts in deciding such emotive issues will be contested, as has happened with the Ayodhya judgement. But the feelings of the majority can no longer be ignored, derided or derailed.

The author is a freelance writer. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment