views

Within an electorate as vast as India's, certain categories might get overlooked within bigger, more 'newsworthy' statistics. But when they are internal refugees uprooted by civil unrest and denied basic amenities, denying them the right to vote makes a mockery of our democratic institutions. The current Lok Sabha elections are being marred by the Election Commission's inability to take a clear stand against political forces for the rights of refugees across the country.

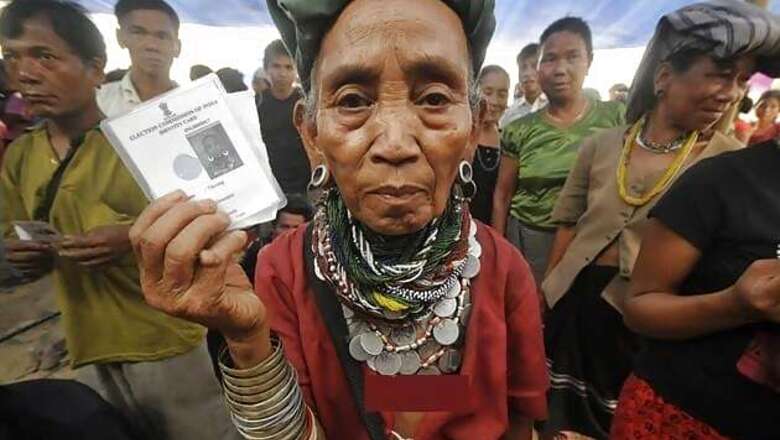

Events today have reinforced the feeling that the EC has not been able to stare down political forces out to marginalise the already oppressed. In 1997, an unprecedented outburst of communal frenzy led to the exodus of thousands of members of the Bru (or Reang) community from Mizoram into neighbouring Tripura.

In an echo of similar refugee stories elsewhere in India, the Brus never returned home and have been put up in these camps in Tripura ever since.

This festering political mess has now returned to haunt the EC. In March 2014, Mizoram Chief Minister Lalthanhawla wrote to Chief Election Commissioner VS Sampath asking that the Bru refugee be barred from voting in Tripura.

In an argument as difficult to agree with as it is inhumane, Lalthanhawla said the refugees had two choices. If they wanted to vote for his state's Lok Sabha seat, they would have to vote in Mizoram, not Tripura, and if they voted in Tripura, their names should be struck off the voters' list in Mizoram.

Meanwhile, Bru representatives appealed to the Commission to be allowed to vote in their camps, which they were allowed to, and in fact less than a week before the first phase of polls began on April 7, the Brus were the first to cast their postal ballots and start Elections 2014 in the country. Although a meagre 2,500 of the more than 11,000 eligible Brus voted, their gesture is a matter of hope for the country and its political system.

This, however, has snowballed into a major confrontation the Election Commission is not prepared for, with Mizo groups protesting the Bru vote and announcing a 12-hour state bandh. The Election Commission has therefore deferred voting in Mizoram indefinitely as it tries to resolve the matter. With the state government effectively supporting the protesters, the Commission will have to decide whether to go tough on the government or try to find an alternate solution.

In UP's Muzaffarnagar, too, scars from the 2013 communal riots are a very long way from healing. Meanwhile, BJP Lok Sabha candidate and one of the accused in the riots, Hukum Singh has recently said he would oppose riot refugees voting in his constituency of Kairana.

His reasoning seems to be based on a leaf from Mizo CM Lalthanhawla's book. They were living, Singh says, on government land illegally, and were registered to vote in their native villages.

Therefore, they would have to return to their villages to vote or forfeit their right.

However, the more than 7,000 riot refugees there are in too much physical fear to attempt to return to their native villages. This is apart from 33,000 other riot victims who also live in refugee camps elsewhere and whose status, similarly, is precarious as far as permanent residence is concerned.

The Election Commission does have a system to account for displaced persons eligible for voting. In early February, it launched a special drive in 22 villages in the riot-affected areas where refugees had been put up, and nodal officers began registering the names of the refugees there.

However, with local strongmen like Singh opposing the refugees right to vote in these settlements, there is no clarity on whether these unfortunate citizens, who suffered so much during the riots, might be able to exercise their basic right as Indian citizens. As the time for polling approaches, this unanswered question might cause more volatility in an already tense part of the state.

Such situations have been repeated every time a communal or sectarian conflict has erupted in India. In Gujarat 2002, Muslim refugees in relief camps expressed unwillingness to return to their places of permanent residence to vote in state elections that year, while others left the state itself, as did victims of the anti-Sikh riots of 1984.

Even as India has yet to evolve a permanent mechanism to deal with long-term refugees and internally displaced persons, the postal ballot system goes a long way to ensure such victims can at least continue with some of the basic functions of citizenship. But in the face of increased bigotry and intransigence by local political forces, perhaps it is time the Election Commission came down hard on such moves to rob refugees of their remaining dignity.

Comments

0 comment