views

In January this year, Facebook revealed that it is disclosing every bit of information that it collects about you, outside of its platform. This came at a time when scrutiny on Facebook's data collection practices became a regular thing. The list is buried deep in the settings for all users, and can be accessed by going to settings, selecting privacy settings, accessing 'Your Facebook Information', and from there, selecting the 'off-Facebook activity' option.

The disclosure came at a crunch time for the brand – its reputation in the security and privacy space was absolutely battered in light of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, and chief executive Mark Zuckerberg’s desperate attempt to show his company still ‘cares’ was by giving users a look at everything that his company knows about you. This, however, does reveal something a bit more problematic – something that brings numerous other parties into the scope of this conversation.

The circus of data

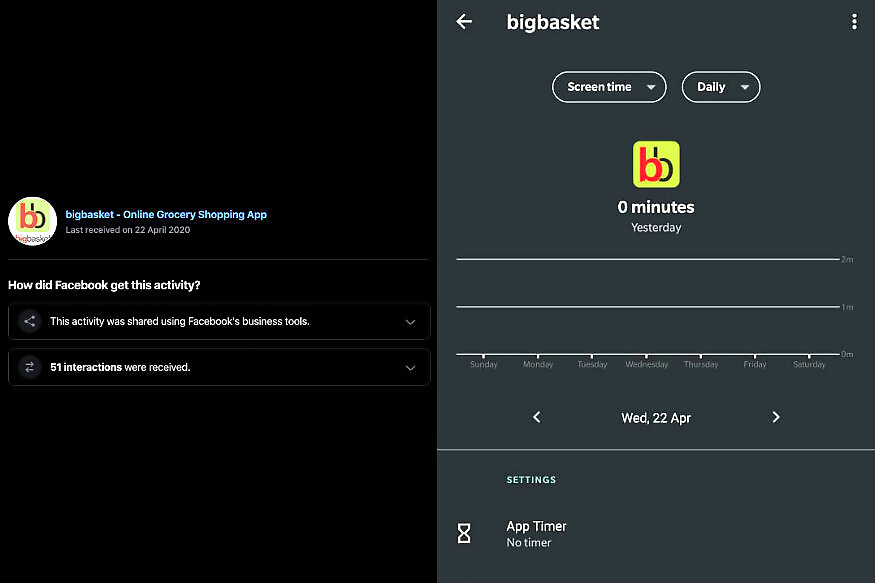

Some key services attracted my attention when I downloaded and inspected the full draft of data that Facebook has about me. The first of the lot is BigBasket – a grocery delivery app that I have not used in a long time. Accessing Facebook’s off-platform activity data showed that I made 51 interactions with the BigBasket app yesterday, April 22. Eerily, I have not opened the app for weeks, let alone access it extensively yesterday. What makes things more alarming is that I only ever used my phone number and a password to sign in to BigBasket, which I did over a month ago. My Facebook account was, in no way, linked to BigBasket.

Intriguingly, the only related activity that I could trace to anything related to BigBasket was the consignment of essential groceries that I ordered through Amazon Pantry’s web portal. Apart from being a rival grocery service, I was also signed in to Facebook, and the web portal of the service was open in a different tab – understandable in terms of cross-site cookie tracking.

However, this does nothing to explain my BigBasket activity, or allay my fears of being tracked across sites despite having cookie tracking turned off. A closer look further revealed sites and apps to which I never gave Facebook access to – Practo, Pokemon Go and The New York Times Android app, among others. With these services never being granted visible and cognisant permission by me, the matter then comes down to scrutinising the privacy and data sharing policies of these apps – something that almost no user will likely take the pain of.

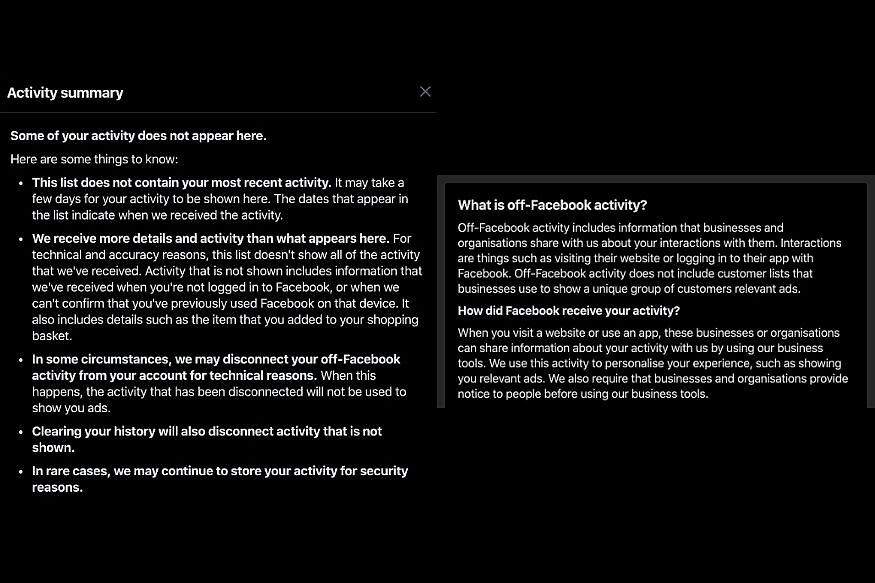

It is this that makes Facebook’s off-platform activity particularly alarming, and worth paying significant attention to. While you can erase all of the activity and un-link your profile from these services, there are a few worrying clauses here. Facebook’s disclosure of data in the off-platform activity section states:

“We receive more details and activity than what appears here. For technical and accuracy reasons, this list doesn't show all of the activity that we've received. Activity that is not shown includes information that we've received when you're not logged in to Facebook, or when we can't confirm that you've previously used Facebook on that device. It also includes details such as the item that you added to your shopping basket.”

“In rare cases, we may continue to store your activity for security reasons.”

Facebook may not face the blame alone here, for even the respective apps made use of Facebook’s Business Tools, which include the prolific Facebook Pixel. In other words, pretty much everyone involved in this circle is aware of how your data is being traded and spread around. Only, you do not have much that you can do, except for delete as much information as you can from the list that is shown to you by Facebook, in good faith.

How Facebook tracks you

For all those times that, for the sake of convenience you chose to log in to a service with Facebook, you essentially gave away all your information for Facebook to sell for its business. Such information, as Facebook says in a nutshell, is used to “show you things that you might be interested in, such as events that you might want to go to, (and) show you relevant ads that introduce you to new products and services.”

Such practices are not new, and a sizeable portion of users are of the opinion that if letting companies serve harmless, non-invasive but relevant ads helps keep their lights on, it is a reasonable exchange since Facebook technically does not charge its users for using its platform. In the high profile testimony by Zuckerberg at the US Capitol earlier in 2019, the executive’s line “Senator, we sell ads” became wildly popular as the focal point of a billion privacy debates that Facebook found itself in the middle of.

But, the ever important conversation lies in just how much personal data invasion by Facebook can be deemed acceptable, especially for what you do outside of its platform. To understand this, a glance through Facebook’s legal documentation for its ‘business tools’ – a set of tools and services that are used by ventures to trade information with them – reveals interesting data.

“‘Contact Information’ consists of information that personally identifies individuals, such as names, email addresses and phone numbers that we use for matching purposes only. We will hash Contact Information that you send to us … When using a Facebook image pixel or other Facebook Business Tools, you or your service provider must hash Contact Information in a manner specified by us before transmission.”

“‘Event Data’ includes other information that you share about your customers and the actions that they take on your websites and apps or in your shops, such as visits to your sites, installations of your apps and purchases of your products.”

In other words, each action on the platform is converted into an identifiable vector, which can then be computed to “generate analytics and insights about (a business’) customers and the use of (related) apps, websites, products and services.” These include a full suite of parameters that can identify when you visited a site, from which region, your entire activity within that site, and so on. This gives Facebook the ability to show you relevant ads. For instance, if you spent quite some time through the day browsing through an indexing site for doctors, Facebook can use that information to offer you ads of medical insurance, online medicine delivery services near your location, and so on.

Downloading a copy of your entire information from Facebook also reveals that even with location permissions switched off, it still knows your “primary location”, which is collated from a host of activities around you – it does not matter if you disallow location services for Facebook on your phones and websites. It is this that makes your off-Facebook activity so relevant to the platform, and at times, even more relevant than what you do when you are on it.

Comments

0 comment