views

Understanding the Problem

Identify the question. You must first determine exactly what it is you are trying to prove. This question will also serve as the final statement in the proof. In this step, you also want to define the assumptions that you will be working under. Identifying the question and the necessary assumptions gives you a starting point to understanding the problem and working the proof.

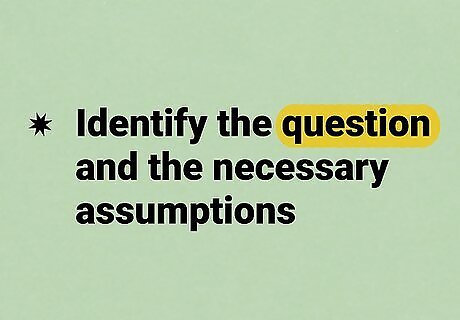

Draw diagrams. When trying to understand the inner working of a math problem, sometimes the easiest way is to draw a diagram of what is happening. Diagrams are particularly important in geometry proofs, as they help you visualize what you are actually trying to prove. Use the information given in the problem to sketch a drawing of the proof. Label the knowns and unknowns. As you work through the proof, draw in necessary information that provides evidence for the proof.

Study proofs of related theorems. Proofs are difficult to learn to write, but one excellent way to learn proofs is to study related theorems and how those were proved. Realize that a proof is just a good argument with every step justified. You can find many proofs to study online or in a textbook.

Ask questions. It’s perfectly okay to get stuck on a proof. Ask your teacher or fellow classmates if you have questions. They might have similar questions and you can work through the problems together. It’s better to ask and get clarification than to stumble blindly through the proof. Meet with your teacher out of class for extra instruction.

Formatting a Proof

Define mathematical proofs. A mathematical proof is a series of logical statements supported by theorems and definitions that prove the truth of another mathematical statement. Proofs are the only way to know that a statement is mathematically valid. Being able to write a mathematical proof indicates a fundamental understanding of the problem itself and all of the concepts used in the problem. Proofs also force you to look at mathematics in a new and exciting way. Just by trying to prove something you gain knowledge and understanding even if your proof ultimately doesn’t work.

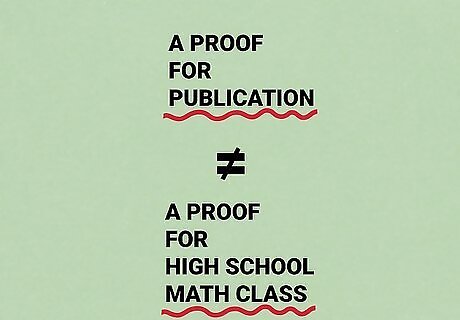

Know your audience. Before writing a proof, you need to think about the audience that you’re writing for and what information they already know. If you are writing a proof for publication, you will write it differently than writing a proof for your high school math class. Knowing your audience allows you to write the proof in a way that they will understand given the amount of background knowledge that they have.

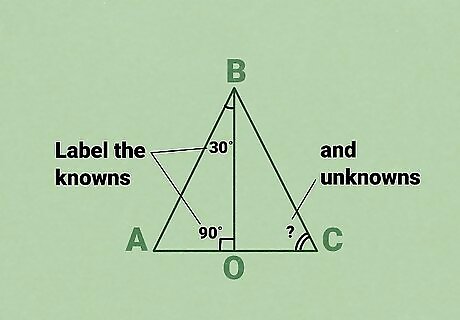

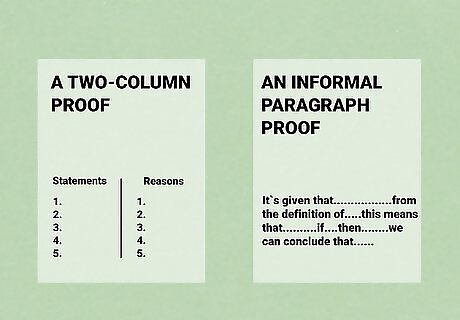

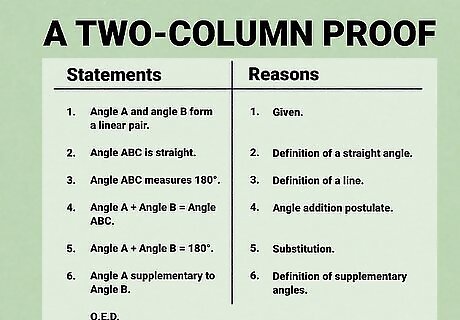

Identify the type of proof you are writing. There are a few different types of proofs and the one you choose depends on your audience and the assignment. If you’re unsure which version to use, ask your teacher for guidance. In high school, you may be expected to write your proof in a specific format such as a formal two-column proof. A two-column proof is a setup that puts givens and statements in one column and the supporting evidence next to it in a second column. They are very commonly used in geometry. An informal paragraph proof uses grammatically correct statements and fewer symbols. At higher levels, you should always use an informal proof.

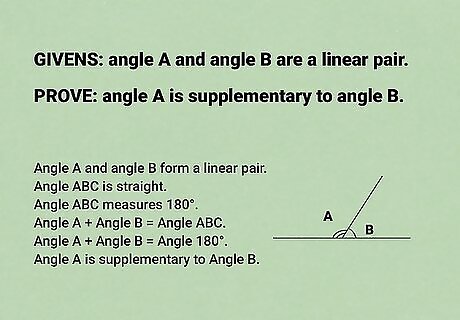

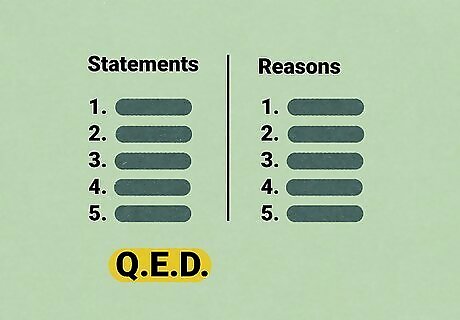

Write the two-column proof as an outline. The two-column proof is an easy way to organize your thoughts and think through the problem. Draw a line down the middle of the page and write all givens and statements on the left side. Write the corresponding definitions/theorems on the right side, next to the givens they support. For example: Angle A and angle B form a linear pair. Given. Angle ABC is straight. Definition of a straight angle. Angle ABC measures 180°. Definition of a line. Angle A + Angle B = Angle ABC. Angle addition postulate. Angle A + Angle B = 180°. Substitution. Angle A supplementary to Angle B. Definition of supplementary angles. Q.E.D.

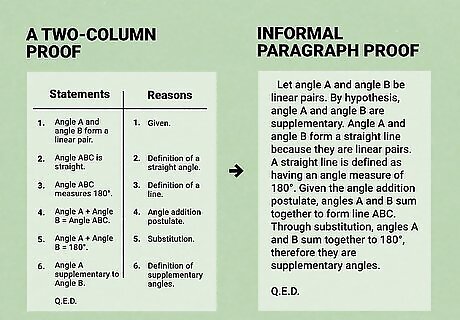

Convert the two-column proof to an informal written proof. Using the two-column proof as a foundation, write the informal paragraph form of your proof without too many symbols and abbreviations. For example: Let angle A and angle B be linear pairs. By hypothesis, angle A and angle B are supplementary. Angle A and angle B form a straight line because they are linear pairs. A straight line is defined as having an angle measure of 180°. Given the angle addition postulate, angles A and B sum together to form line ABC. Through substitution, angles A and B sum together to 180°, therefore they are supplementary angles. Q.E.D.

Writing the Proof

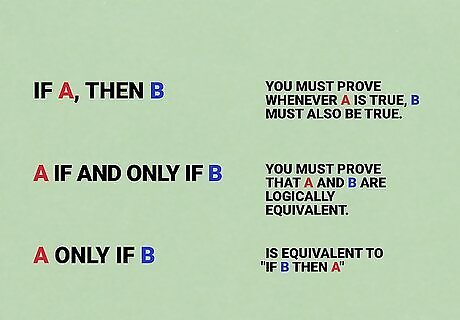

Learn the vocabulary of a proof. There are certain statements and phrases that you will see over and over in a mathematical proof. These are phrases that you need to be familiar with and know how to use properly when writing your own proof. “If A, then B” statements mean that you must prove whenever A is true, B must also be true. “A if and only if B” means that you must prove that A and B are logically equivalent. Prove both “if A, then B” and “if B, then A”. “A only if B” is equivalent to “if B then A”. When composing the proof, avoid using “I”, but use “we” instead.

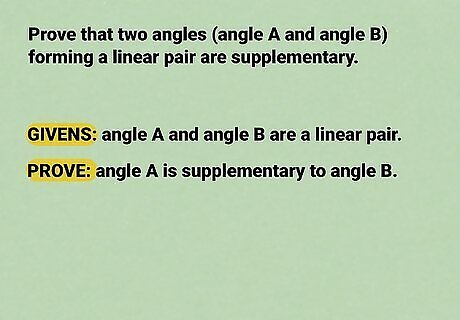

Write down all givens. When composing a proof, the first step is to identify and write down all of the givens. This is the best place to start because it helps you think through what is known and what information you will need to complete the proof. Read through the problem and write down each given. For example: Prove that two angles (angle A and angle B) forming a linear pair are supplementary. Givens: angle A and angle B are a linear pair Prove: angle A is supplementary to angle B

Define all variables. In addition to writing the givens, it is helpful to define all of the variables. Write the definitions at the beginning of the proof to avoid confusion for the reader. If variables are not defined, a reader can easily get lost when trying to understand your proof. Don’t use any variables in your proof that haven’t been defined. For example: Variables are the angle measure of angle A and measure of angle B.

Work through the proof backwards. It’s often easiest to think through the problem backwards. Start with the conclusion, what you’re trying to prove, and think about the steps that can get you to the beginning. Manipulate the steps from the beginning and the end to see if you can make them look like each other. Use the givens, definitions you have learned, and proofs that are similar to the one you’re working on. Ask yourself questions as you move along. "Why is this so?" and "Is there any way this can be false?" are good questions for every statement or claim. Remember to rewrite the steps in the proper order for the final proof. For example: If angle A and B are supplementary, they must sum to 180°. The two angles combine together to form line ABC. You know they make a line because of the definition of a linear pairs. Because a line is 180°, you can use substitution to prove that angle A and angle B add up to 180°.

Order your steps logically. Start the proof at the beginning and work towards the conclusion. Although it is helpful to think about the proof by starting with the conclusion and working backwards, when you actually write the proof, state the conclusion at the end. It needs to flow from one statement to the other, with support for each statement, so that there is no reason to doubt the validity of your proof. Start by stating the assumptions you are working with. Include simple and obvious steps so a reader doesn’t have to wonder how you got from one step to another. Writing multiple drafts for your proofs is not uncommon. Keep rearranging until all of the steps are in the most logical order. For example: Start with the beginning. Angle A and angle B form a linear pair. Angle ABC is straight. Angle ABC measures 180°. Angle A + Angle B = Angle ABC. Angle A + Angle B = Angle 180°. Angle A is supplementary to Angle B.

Avoid using arrows and abbreviations in the written proof. When you are sketching out the plan for your proof, you can use shorthand and symbols, but when writing the final proof, symbols such as arrows can confuse the reader. Instead, use words like “then” or “therefore”. Exceptions to using abbreviations include, e.g. (for example) and i.e. (that is), but be sure that you are using them properly.

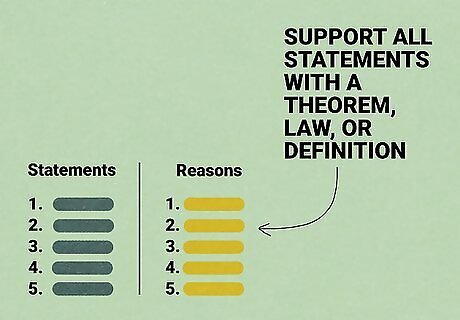

Support all statements with a theorem, law, or definition. A proof is only as good as the evidence used. You cannot make a statement without supporting it with a definition. Reference other proofs that are similar to the one you are working on for example evidence. Try to apply your proof to a case where it should fail, and see whether it actually does. If it doesn’t fail, rework the proof so that it does. Many geometric proofs are written as a two-column proof, with the statement and the evidence. A formal mathematical proof for publication is written as a paragraph with proper grammar.

End with a conclusion or Q.E.D. The last statement of the proof should be the concept you were trying to prove. Once you have made this statement, ending the proof with a final concluding symbol such as Q.E.D. or a filled-in square indicates that the proof is completely finished. Q.E.D. (quod erat demonstrandum, which is Latin for "which was to be shown"). If you're not sure if your proof is correct, just write a few sentences saying what your conclusion was and why it is significant.

Comments

0 comment