views

Planning Your Story

Read touching stories written by other authors. When planning your own touching story, it is helpful to think of other touching stories that you’ve read, reflecting on what you liked, what you didn’t like, and what you might have done differently. Without copying them, you can choose specific elements of a variety of touching stories to help shape your own story. Perhaps you’re drawn to stories that have a lot of dialogue and would like to incorporate that into your work. Or, you might not like long, drawn out setting descriptions and may choose to write shorter descriptions. You might find that you really enjoy reading touching stories in which love prevails over an external triumph. That’s a wonderful reflection, as it gives you a potential starting point for your own touching story.

Make your story relatable. One engaging feature of a touching story is that it is relatable and readers can imagine and feel what the characters are going through, so you want to evoke an emotion many people can relate to. The situation can be vary, as the emotion is what people connect with most. This helps ensure that the maximum number of readers will really get into your touching story. Be creative and don't do something too common; nobody wants to read yet another variation of a story they've read too many times already. Some examples include: Loss of a loved one or pet Marriage-related situations A big move Finding love Forgiveness Going away to college Getting a new job Going on a journey of self discovery A kind gesture met by another kind gesture

Develop the characters. The most important characters are the protagonists ("hero") and the antagonist ("villain"). However, you will want to add some more minor characters, otherwise, the touching story will not be as interesting. When you are making up characters, write at least some backstory about each of them. Even if you don't put this in the story, it's good to keep in mind so your characters will always act "in character". Figure out what role each person has in the plot. You might have a notebook specifically for character development, dedicating a page to each character in which you jot down notes about them. You don’t have to use every character note that you write down. It’s better to have too much than too little, as you can always cut or revise details later. This is where you can bring your characters to life. Imagine your protagonist. Is she from a small town? How did she end up in the big city? Where did she meet the love of her life who she’ll connect with later in the story? What’s her favorite band? Food? Author?

Map out your touching story. Many new authors want to jump right in and write; however, it is better to do some planning beforehand. Making an outline or chart of characters, backstories, conflict, and settings helps ensure that the touching story is consistent and the plot makes sense. This also allows you to fill in any gaps in your story and change points around as necessary. Perhaps the most famous example of plotting a story is J.K. Rowling’s chart for the Harry Potter novels. Notice that she pays attention to details, planning out the action for each month of the story, as well as the plots and subplots. Everything is managed and accounted for in her hand-written spreadsheet. You should refer to your character pages while plotting to maintain consistency.

Develop your setting. The setting of your touching story is vitally important, serving as more than a passive backdrop. Instead, characters interact with the setting in this type of story, and the setting can, at times, offer a sort of locomotion that propels the story along. One way to relate to your audience, too, is through setting, making your story even more robust. Think about where you want your story to take place. Imagine the house, the store, the school, the city, the state, the country, and write down details of your location in your notebook. Also consider when this is taking place. Determine what season and time your touching story is set. Does it happen to be during a holiday? Do you imagine this taking place in one location, such as a boat dock as they wave goodbye to one another? Or do you see your story spanning sunrise and sunset both, on a boat dock and at a high school football game?

Choose your point of view. Point of view is also important in a touching story as you want your readers to sympathize with the characters. Do you want to tell your touching story from the point of view of one character in particular so that readers become invested in them primarily, or perhaps as a third-person narrator so that readers are paying more equal attention to all of your characters? A first-person point of view is useful because you can give your readers access to your protagonist's (or another character's) inner thoughts, their feelings, their reactions, and the story as they experience it. This interior perspective is useful because readers become invested in that character. However, make sure you only write from this character's perspective, presenting only information they would reasonably know. On the other hand, if you have a third-person narrator in your story, a narrator that is removed and tells the story to the readers, you are able to describe more characters, but with less emotional depth. You may also incorporate free indirect discourse, which allows readers partial access to a character’s thoughts while maintaining that third-person narrator. One benefit of a third-person point of view is that you can choose to use an omniscient narrator, allowing you to explore the thoughts and feelings of multiple characters.

Writing Your Story

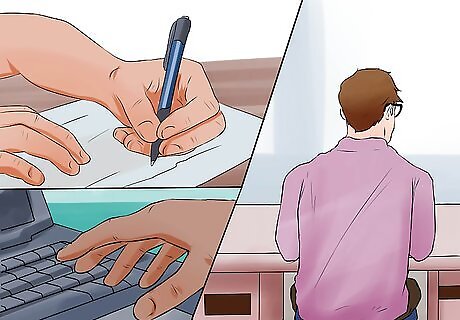

Create your own writing routine. Often you won’t know what works best for you until you sit down to write. You might decide that a pen and paper is best, or you may determine that typing on a computer works better for you. Also, you might find that writing in a particular room in your house, or in a chair outside, or at a coffee house inspires creativity. Some research suggests that our writing and retention improve when we write by hand because it slows us down, allowing us to think better.

Don’t focus on the details. Resist the temptation to name characters, places, and the story itself, initially. Sometimes when people write, they spend too much time coming up with names rather than characterization, plot details, and other vital elements. You can (and should) go back later and work on naming your characters. Although you know your characters fairly well by now, having imagined them, written notes about them, and mapped them into your larger touching story, don’t worry about details right now like names. What’s important at this stage is the substance and to make sure that you’re focusing on writing a touching rather than gimmicky story.

Make emotional connections. What makes touching stories so effective is that the reader can emotionally connect and relate to the story, setting, characters, and plot. This emotional connection is typically predicated on something very simple, such as love or compassion, so make sure that you don’t overcomplicate or over-sentimentalize your story. For example, while it’s possible that someone has very, very bad luck, most readers won’t emotionally connect to a story in which the protagonist has over-the-top experiences (like being forced to drive a runaway train full of dynamite while trying to save her one, true love). Less is better, allowing the characters and storyline to really shine through.

Avoid being overly-sentimental. You can write a deeply touching story that resonates with your audience and not be overly sentimental. In fact, you want to avoid sentimentality, instead recognizing that you can convey thoughts, emotions, struggles, and experiences without over-expressions of emotion. Don’t avoid emotions in your touching story, just avoid excess. You can tell your reader what a character is feeling very directly by just stating it. For example, “Kurt was feeling anxious as he stood on the front porch, staring at the front door that he hadn’t seen in 27 years.” Or you can indirectly offer this by using an adjective to describe a person or a thing (noun), which tells the reader the character’s feelings about that noun, giving an indirect glimpse at their feelings. For example, “Chloe made her way down the busy street, hoping that she’d see Samantha before her horrible boss made her go back to work.” It's best to show your characters' emotions through actions rather than by telling the reader how they feel. Not only will this make your story more interesting, it also helps you avoid being overly sentimental. For example, "Hallie removed the photo from the side table and studied the smile on his face, looking for falsehoods. After the first tear splashed against the glass frame, she stashed the photo in the drawer of the side table, determined never to look at it again."

Don’t be melodramatic. Remember, you want your readers to relate to and connect with your touching story and really become emotionally invested, so be intentional with your plot, actions, and characters so that you don’t slip into a sensational or melodramatic story. With a touching story, less is more. Be realistic and you’ll be relatable. A character may have a sick parent who they are unable to financially care for, which is realistic and relatable. But it would be melodramatic to say that character also has a sick child, missing dog, and that they lost their job. What is one touching aspect of your story that you think your readers could connect with?

Make sure your tone helps evoke emotions in your reader. You’ll use style, tone, and vocabulary to manipulate your writing so that your story is touching, authentic, and relatable. Also, match your tone to your audience and preferred publisher, if you have one. Your tone, style, and even your word choices will be different depending on who and what you’re writing for. Your word choices will impact the mood, tone, and action of your touching story and determine how your reader responds to your touching story. If you want to set a positive tone, for example, you might describe your protagonist as modest, appreciative, cheerful, or benevolent. On the other hand, you might describe your protagonist’s feelings as she searches the woods for her elderly Labrador Retriever one night as frantic, desperate, and terrified.

Make your characters sympathetic. Readers emotionally resonate with sympathetic characters, making them likable and relatable, both vital to an effective touching story. Just like before, remember that less is more here. Don’t overwhelm your reader with character traits; instead, be judicious with how you portray your character, giving more meaning to that which you do offer. Typically a sympathetic character will face an obstacle, or have a worthwhile or even noble cause, or they may have a passion or love to pursue. These aspects humanize your character and give your reader a reason to root for them.

Be mindful of emotional resonance. You want your reader to feel what’s happening in your touching story, and you’ll do this by bringing the characters to life and telling a believable story. Another trick is to make your story emotionally resonant, helping your readers feel what your characters feel. Rather than tell your reader how your character feels, occasionally tell your reader how the character reacts to a situation. What do they do because of how they are feeling? For example, instead of saying, “Jose was devastated when he learned that Anna had married Sam in his absence,” tell the reader what Jose did. “Jose buried his head in the pillow and screamed after learning that Anna had married Sam while he was gone. He cried and yelled into that pillow to exhaustion, finally falling into a disturbed and restless sleep.”

Write now and edit later. Write your first draft with the understanding that it will need a lot of work. Refer to your story map frequently as you write, but don’t worry about editing yet. Spend your time and energy generating the first draft of your story, focusing on developing your plot and characterization. #*Editing is another step in the writing process.

Remember the back story. You can never have too much backstory, even about the most minor characters. Remember that Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Tolkien, and J.K. Rowling all paid attention to backstory and characterization, even for the most minor characters. You need to remember, though, not to overwhelm your reader with too much backstory at one time. You might need to spread out a character’s backstory over several chapters so that it’s not too much at once. If you’re writing a shorter story, you might not have the space to spread out the backstory. In that case, choose the most important details that will help your reader engage emotionally with the characters and storyline.

Revising and Publishing Your Story

Embrace the writing process. Touching stories are emotionally complex, and you should allow yourself the opportunity to revise, focusing on different points and areas with each “second look.” Every time you revise your touching story, approach your text with one goal in mind, such as working on character development, or transitions, or dialogue. Working on one area at a time will help you stay focused, not getting sidetracked by other issues that you notice.

Read your touching story out loud. Whether you read out loud to yourself, your Aunt Martha, or your cat, reading your story out loud will make you a better writer. Even better is to ask someone to read your story out loud to you. Hearing a story allows you or your readers to access the story in a different way, and will help you identify issues with tone, grammar, and syntax.

Save several copies. While revising, make sure that you have your story saved in more than one space. Accidents happen and you don’t want to run the risk of losing your work. Consider putting all of your drafts on a removable storage device or in cloud storage. And remember, don’t delete your drafts. Save each one and name it appropriately, just in case you want to go back and use or refer to something from a previous version of your work.

Get feedback on your work. Ask someone you trust to read your touching story and give you feedback. They will be able to point out things that you may have forgotten to mention or areas that do not make sense to them. Keep in mind that they may not only have things to say about the story itself; they may have comments about the grammar as well. For example, a sentence that sounds fine to you may actually be worded awkwardly.

Decide if you want to be paid for your work. Whether you would like to be paid for your story or not will dictate what avenue of publication you pursue. If you want to share your work without compensation, there are websites that will allow you to publish your work for free. If you decide that you’d like to be paid for your story, consider sending your story to a publishing company (and some magazines) or self-publish your text.

Keep your work off of the internet. Remember, once something is on the internet, it can never be truly erased, so consider your options before sharing your work digitally. When you sell your story, you’re actually selling the rights to publish your work, not ownership of the story. There are different rules and rights depending on which country you’re in, so make sure to look up what options are available for you. Until you’re certain what route you’d like to pursue, though, don’t share your work digitally with others.

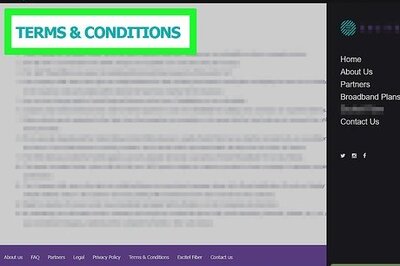

Check publisher information before sending out your story. If you decide to publish your work, do some research before you send your touching story out. Consider if you want to be published in a magazine, or part of an anthology, or perhaps your novel will stand alone. Also, consider if you want an agent or if you’d like to represent yourself in negotiations over your work. You can hire an agent who will do the work of contacting editors and negotiating compensation for you. You can also self-publish, which will require that you cover the cost of the publication. You can represent yourself and contact publishing houses and editors directly.

Comments

0 comment