views

Analysts have noted that given the supply constraints, many wealthy countries are still standing in queue for vaccine doses despite their purchasing power. At the same time, the limited supply of vaccines is extremely iniquitously distributed, with 90 per cent of all the vaccines produced by the top four global vaccine manufacturers in the United States (US) and Europe having been administered on populations within North America and Europe in the first quarter of 2021. While India’s vaccination plans faltered in the face of a deadly second wave, the regular global comparisons in the Indian media compare India predominantly with the USA and European countries and conclude that the coverage is insignificant, and the rollout too slow.

More Relevant Comparisons

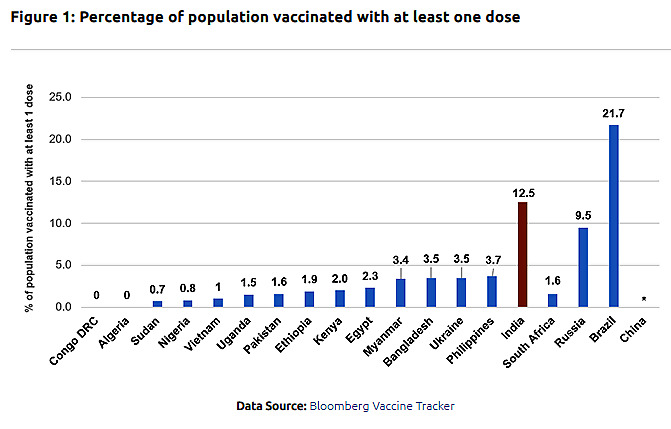

However, when we compare India with countries of comparable socio-economic and demographic status, a completely different reality emerges. Figure 1 explores vaccination coverage in terms of the proportion of population with at least one dose administered among the 15 most populous low- and lower- middle-income countries, according to the World Bank classification (Gross National Income (GNI) per capita below US $4,045). It also includes the BRICS countries, each of which is richer than India (GNI per capita of US $2,120). Among the 15 most populous low- and lower- middle-income countries, India has the highest population coverage of at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccines. Within BRICS, only China and Brazil have managed to do better than India, although disaggregated data for the former is not available. Interestingly, Russia, despite being major vaccine manufacturer, has done worse than India on this count.

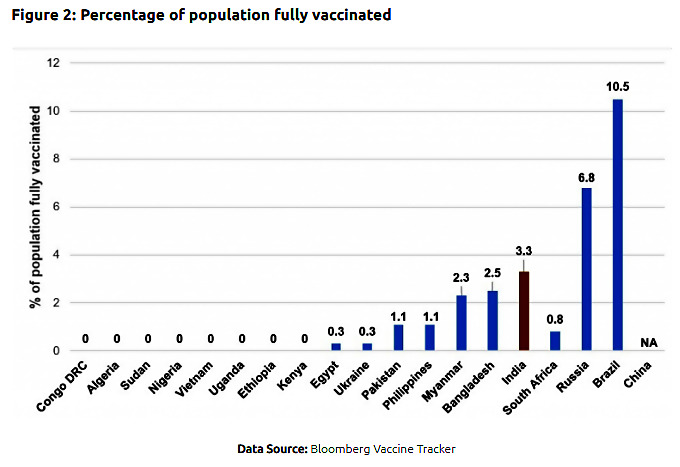

When it comes to the fully vaccinated population, India’s performance looks relatively weaker at just 3.3 per cent of the overall population, although it is still the highest among the large low- and lower- middle-income countries. Among BRICS countries, although India’s absolute numbers of vaccine doses administered fall behind only to China, the proportion of fully vaccinated population is considerably lower than China, Russia and Brazil—three relatively richer countries. To be sure, this analysis does not show that India has been successful in its vaccination effort, only that India’s vaccination rollout is happening in the global context of vaccine shortages, and a staggeringly unequal vaccine distribution in favour of the rich countries. India has no other solution in sight than to expand domestic production, to help itself and other developing countries.

The Global Race to Secure Vaccines

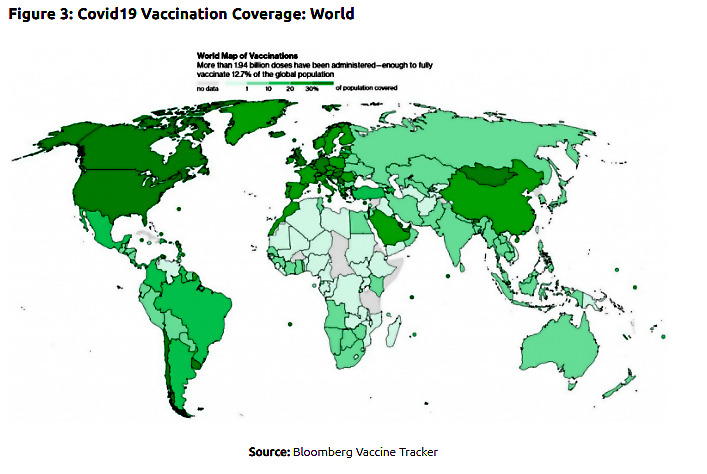

On the path to recovery, each country today is scrambling between the pillars of diplomacy, public health and economics, and the obvious and only solution in the medium term is vaccines. However, with more than 1.91 billion doses administered globally, the vaccination coverage is still inequitable and slow, covering 12.5 per cent of the global population. China is leading the world with 639 million doses, followed by the US with 295 million doses administered, as of 31st May 2021. The average rate of inoculations stands at 33.5 million doses a day, a rate at which it will take a year to cover 75 percent of the population resulting in a good level of global immunity against the COVID-19 virus.

While close to 40 per cent of the total doses administered globally have gone to people from High- and Upper-middle Income countries, they constitute less than 16 per cent of the world’s population. It can be further noted that the wealthiest 70 countries in the world currently account for 45 per cent of all the vaccinations administered, while accounting for only 23 per cent of the world’s population. Clearly, access to life-saving vaccines and toolkits is neither fair nor equitable.

Experts have gone on to predict that if vaccines continue to remain elusive to a majority of the global population, the pandemic could drag on for an additional seven years. The COVAX facility, co-led by the WHO, GAVI and Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI), is well behind its commitment of two billion doses to 92 of the poorest countries of the world, partly caused by its over-dependence on the Serum Institute of India for vaccines, who got overwhelmed with the second wave. But even with supply chains falling in place, it would only help around 20 per cent of people from low- and middle- income countries. As long as crucial weapons against the disease are available only to the rich countries, the virus will continue to mutate and widen transmission to the poor and unprotected. It further goes on to bolster massive public health dangers and an estimated US $9 trillion worth of economic risks.

India’s Long Path to Herd Immunity

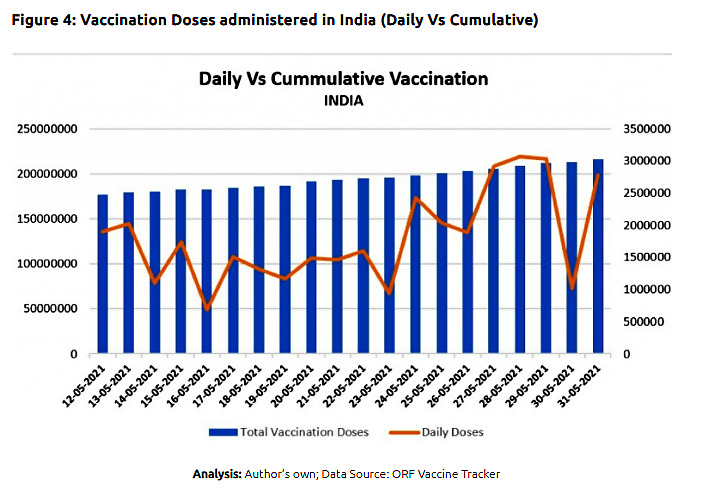

Due to a prolonged phase of country-wide vaccine shortages in the past month, the daily average doses witnessed visible fluctuation. Before falling to as low as 1.4 million doses per day two weeks ago, the numbers have been steadily rising again. It is presently at a seven-day average of 2.5 million doses per day. The average doses peaked at 3.6 million per day in mid-April.

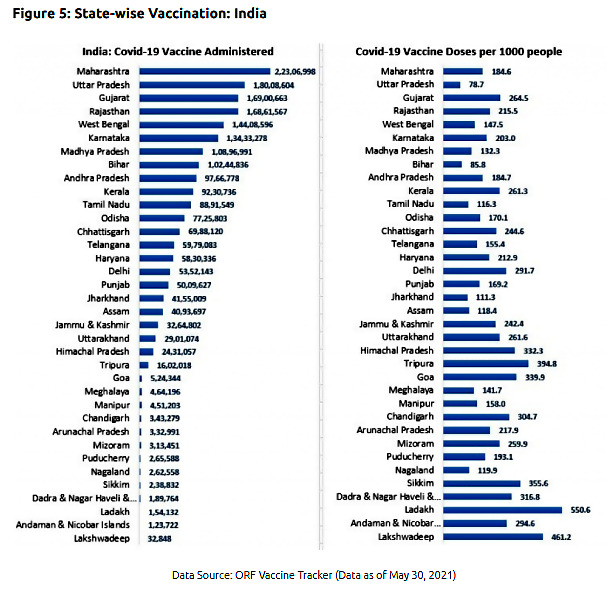

State-wise, Maharashtra leads the country’s tally with 21 million doses in absolute terms. It is closely followed by Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, both with 16 million inoculations each. In relation to population, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar continue to perform poorly with only 72 and 82 doses per 1000 people respectively. The bottom seven states on the national SDG ranking led by Bihar, Jharkhand and UP have also received 24.4 per cent of all the country’s doses while comprising 40 per cent of the country’s population. A broad snapshot of the national numbers can be seen in the charts below.

The Government of India initiated an accelerated Phase-3 of the COVID Immunisation rollout, starting May 1st, by allowing every Indian over the age of 18 years to get vaccinated. But amidst a shortage of vaccines and a collapsed health system, more than 10 states had to delay the vaccination of the 18-44 years age group, and uncertainties about supplies still continue. To remedy the immediate shortage, imported doses of the Russian vaccine, Sputnik V, has been deployed on limited distribution in partnership with Dr Reddy’s Laboratories from May 14th. In addition, the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) has partnered with eight Indian pharmaceutical companies to produce 850 million doses for domestic consumption and worldwide distribution.

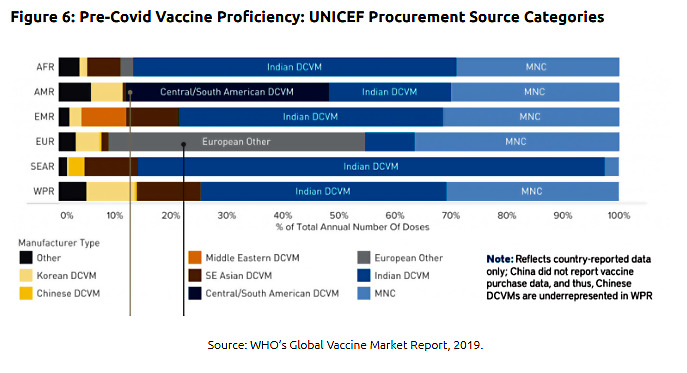

The pre-COVID-19 total global demand for vaccines was estimated to be about three billion doses annually. Since vaccine manufacturers are private sector entities, data on country-level vaccine manufacturing capacity is hard to come by. However, the composition of procurement sources of UNICEF, which is the largest vaccine purchaser in the world, buying more than a billion doses every year is available (Figure 6). As the graph demonstrates, barring the high-income regions of Europe and the Americas, global supply was heavily dependent on Indian vaccines. Given its dominant stature, it is clear that if it started in time, India could have expanded COVID-19 vaccine production capacity—by quickly building new manufacturing units and repurposing existing units—much more easily than any other country in the world.

Going forward, the central government is anticipating an allocation of around 120 million vaccine doses to the states for the month of June 2021. These will be dedicated towards the priority groups of healthcare and frontline workers and adults aged 45+ years (who can access the vaccines for free in government hospitals) as well as for direct procurement by states/UTs and by private hospitals. For May 2021, the comparable number was 79 million doses.

In an important development, the Supreme Court, on June 2, has questioned the Centre on some aspects of the vaccination strategy that seem to impede the speed and scale of the immunisation drive. These aspects include the differential pricing of the vaccines for the States and Union Territories and the logistics of distribution in cold storage chains, amongst others. The Supreme Court argued in favour of a single procurement system for COVID-19 vaccines, citing the decades-old Universal Immunisation Programme led by the Central government as an example of a successful programme that has reduced mortality caused by infectious diseases. The Court has the Centre to submit a detailed affidavit on these issues within two weeks and has emphasised that no effort must be spared to quickly vaccinate as many people as is possible.

As Gopinath and Agarwal from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) assert, the pandemic policy (and consequently the vaccine policy) is the current economic policy. It cannot be over anywhere, unless it is over everywhere. The global vaccination effort requires focused financing, solidarity and substantial investments. Since vaccines are the only real weapon the world has against the virus for now, how India gets back on its feet to fulfil its role as a global vaccine manufacturer will determine how fast the world gets back close to a negotiated normal.

This article was first published on ORF.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here.

Comments

0 comment