views

In the much-hyped assembly election in West Bengal, India’s lone woman chief minister now, Mamata Banerjee, led her party Trinamool Congress to an emphatic victory for the third consecutive time. The mandate is massive, but the bigger question is how to explain it? This author, in one of his previous columns, in the first week of March argued that one of the major reasons for the rise and dominance of Mamata Banerjee in West Bengal politics is the women voters. Mamata has been able to carve out the female electorate through her service delivery model. Nitish Kumar in Bihar and J. Jayalalitha in Tamil Nadu also managed this feat in their respective states. What is unique in West Bengal, however, is that the support from women voters for Mamata has been continuously growing in every election since 2011, and not only has this helped her get a third straight term but also defeat the BJP’s political juggernaut.

The Mandate in Numbers

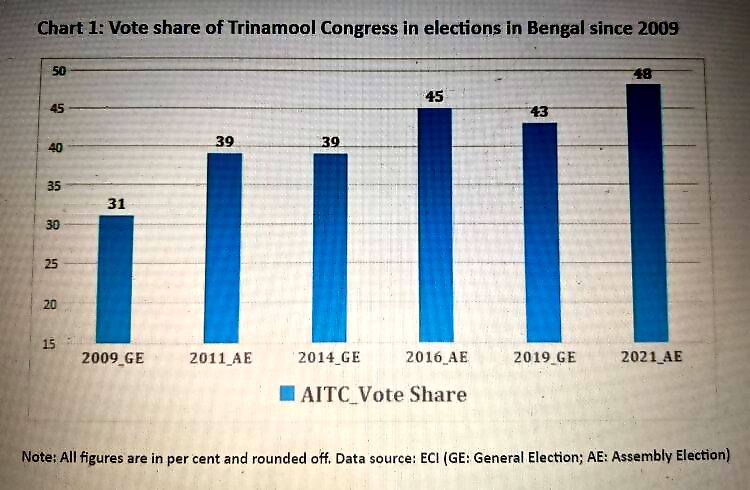

The mandate for Mamata is so huge that it has broken many records. First, Trinamool won the highest-ever seat tally and vote share in West Bengal. The party won 214 of the 292 assembly seats on offer. This is the combined highest ever seat tally of the AITC. In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the party was leading in 214 assembly segments. In terms of assembly elections, this is the TMC’s best harvest ever. Second, the 48 per cent vote share of Trinamool is the highest ever for a single party in Bengal since the 1984 Lok Sabha polls. In that election, the Congress had received 48 per cent votes in the state. The Left Front has got more than 48 per cent votes on some occasions but that was for an alliance. Third, the data from this historic victory of Trinamool suggests that the party has been continuously increasing its vote share in every election since the 2009 Lok Sabha polls in the state except in 2019 when the AITC lost two per cent vote share (see chart 1).

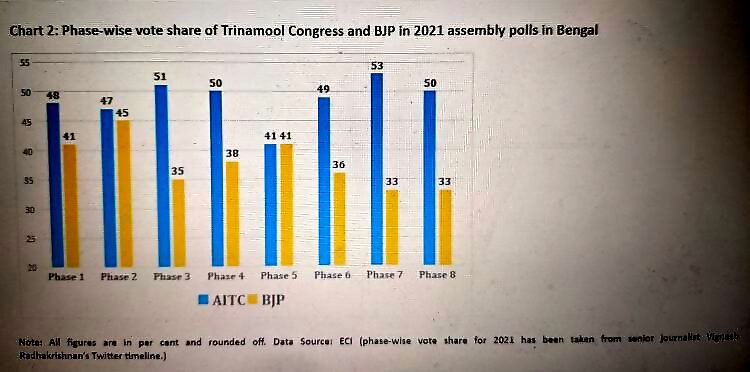

What is more significant is that except a few districts like Bankura, Cooch Behar, Nadia, Pashchim Bardhman and Purulia, the Trinamool Congress has swept almost every district of Bengal. In a long eight-phase election, Trinamool led over the main opposition BJP in every phase, except the fifth where most seats of North Bengal voted. In this phase, both parties received 41 per cent vote share each (see chart 2). Of the eight phases, the AITC led by more than 10 per cent votes over the BJP in five phases. Apart from phase five, the closest gap between the parties is in phase two where Trinamool received 47 per cent vote share while the BJP got 45 per cent. In the last two phases, AITC was leading with 20 per cent and 17 per cent vote share over the BJP.

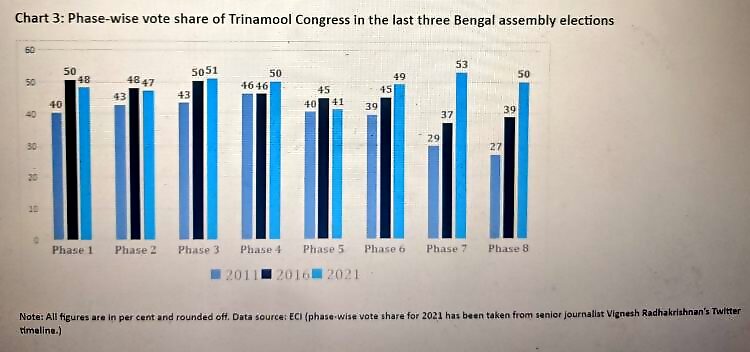

The 2021 assembly election victory of the AITC is so huge that the party has gained in vote share in five out of the eight phases (see chart 3) compared to its own performance in the 2011 and 2016 assembly polls in the state. In the constituencies that went to polls in phase 1 and phase 2, the party lost two per cent and one per cent votes as against 2016. Only in phase 5, the ruling AITC lost a significant share of votes from 2016: around 4 per cent. However, in phases 7 and 8, the party gained 16 per cent and 11 per cent votes respectively. This massive gain for AITC in the final phases came from Malda and Murshidabad districts. These two are Muslim-dominated districts and traditionally supported the Congress for a long time. However, this time they switched their support to the AITC.

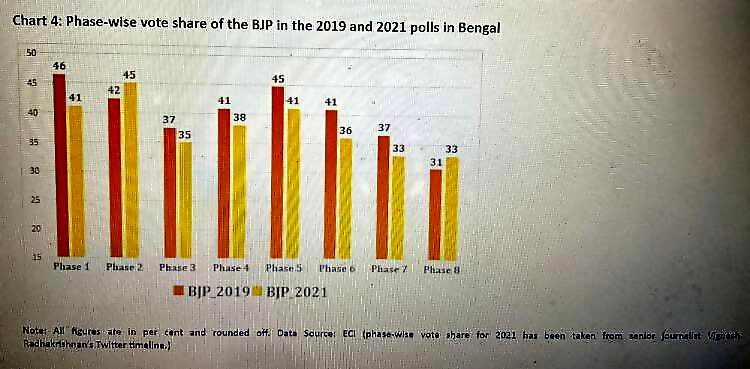

Where was the BJP in this battle? The 2019 Lok Sabha election results had thrown up a surprise when the BJP won 18 Lok Sabha seats with a very impressive vote share (40 per cent). The party swept North Bengal and Jangalmahal regions. This sudden rise of the BJP in the state led many to speculate that the BJP may put up a strong challenge or may dislodge the Mamata Banerjee government in this assembly election. The speculation was based on a close vote share gap (just three per cent) between the AITC and the BJP. However, the BJP was not able to succeed. The party received 38 per cent votes, 10 per cent less than what the AITC got. The huge vote share gap ensured it was a landslide victory for the AITC. The BJP even lost two per cent votes from what it received in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, while at the same time, the AITC gained five per cent votes despite many arguing that Mamata was facing anti-incumbency in the state.

A phase-wise analysis of vote share of the BJP in 2019 and 2021 suggests that the party has lost everywhere except in phase 2 and phase 8 (see chart 4). In phase 2, it was mostly the assembly seats of Medinipur and Bankura districts that went to polls. In phase 8, the BJP gained two per cent votes but it was not significant enough to get translated into more seats. Even in phase 5, when North Bengal voted, the BJP performed well but the party lost four per cent votes compared to 2019.

How did the BJP fail to capitalise on the momentum it got in 2019? First, the BJP in general has been prone to losing its vote share in assembly elections compared to the preceding parliamentary polls. It has happened in most states since 2014. Second, the rise of the BJP in Bengal was not organic. Most of its local leaders were turncoats from different parties, largely the AITC, and its ground workers and supporters were mostly from the Left. The lack of coherence among leaders, cadre and campaign design, lack of credible local faces, and too much dependence on the charisma of central leadership left many fronts open.

A Lesson

The outcome of the 2021 Bengal assembly elections has thrown up two very important political messages that need to be studied more. The first, which is not new, is the role of regional players. Too much centralisation and not investing enough in cultivating and promoting local-level leaders could prove harmful for the BJP in the long run. The Congress has suffered this crisis and sooner or later the BJP could suffer a similar fate. The AITC won for the third time because the party has a strong mass leader like Mamata Banerjee.

Second, the service delivery model has the potential to trump other kinds of politics in elections. Mamata Banerjee’s welfare schemes have provided her an electoral hat-trick. This service delivery model has two key points – first, many of the schemes have a direct beneficiary selection process. Under schemes like Kanyashree and Rupashree, the identification of beneficiaries is done directly, and local middlemen do not have much role to play. Second, many of Mamata’s schemes are women-centric. This empowers women both economically and socially. The empowered women may evaluate the government more based on its performance rather than communal and identity-based sentiments. The sweeping victory of the Trinamool in West Bengal and the Aam Aadmi Party in Delhi have provided us a fresh perspective: that building a service delivery model could be a better campaign strategy than politics of polarisation.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment