views

I am gratified that Christophe Jaffrelot and Gilles Verniers have responded to my piece in News 18 on how BJP shifted the caste game in Uttar Pradesh and why scholars got it wrong on the huge rise of OBC representation in BJP’s political structures with a long rejoinder. I am also deeply amused by their response published here. The facts are entirely opposite to their claims. Scholarly arguments must be based on evidence and the records belie their assertions, on multiple counts.

The hard data in the Mehta-Singh Social Index punctures their scholarly claims on caste representation. And the public record runs counter to their representation of not only my arguments, but strangely enough, of their own published academic writings. Astonishingly, for scholars of such eminence, it also contains factual mistakes on castes in Uttar Pradesh. Academic arguments must be based on evidence, else they run the risk of ending up as mere ideological pamphleteering. To quote Sherlock Holmes from Arthur Conan Doyle’s lovely story, ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’, ‘It is a capital mistake to theorise before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.’

While their factual errors are many, for sake of brevity, here I list only five:

Claim 1: Substantial difference between the Mehta-Singh Social Index findings on caste representation among BJP candidates in 2017 polls and that of Ashoka University’s Trivedi Centre for Political Data (TCPD) data is only because of a difference in the classification of caste categories, not variations in raw data. Jaffrelot/Verniers and TCPD did not count Jats as OBC.

Jaffrelot and Verniers say that ‘the Mehta-Singh Social Index classifies Jats in Uttar Pradesh as OBCs, whereas we [Ashoka University’s TCPD] classify them as intermediary castes.’ They add that ‘For argument’s sake, if we [TCPD] include Jats, too, our dataset would count 113 OBCs.’

My response

Counting Jats as OBCs – or not counting them – is not a trifling matter of mere classification. Surely, Jaffrelot and a university centre like Ashoka’s TCPD, which propounds definitive data on caste, should know that Jats were officially included in the Uttar Pradesh state OBC list for reservation as OBCs over two decades ago, in 2000. If they don’t know, let me refresh their memory.

• The Government of Uttar Pradesh on March 3, 2000 (vide Order No. 334/64-I-2000-46/95 dated 10-3-2000) issued under Section 13 of the UP Public Services (Representation for SCs, STs and OBCs) Act, 1994 included Jats in the UP State List of Backward Classes which made them eligible for reservation under the UP State Public Services.

• Since Jaffrelot and Verniers assert so clearly that, in response to the Mehta-Singh Social Index, they will deign ‘for argument’s sake’ to include Jats in their OBC categorisation for Uttar Pradesh, all I can say is that they are 21 years too late.

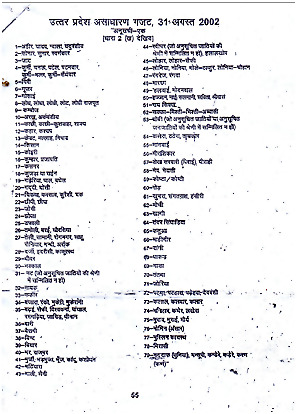

• Ashoka University researchers would have done well to check the UP State Caste List for OBCs (see Figure 1). Jats are listed at No. 3 on a list of 79 castes officially classified as OBC by the state.

• The classification (or lack thereof) of Jats as OBC in the state of Uttar Pradesh is not a matter of academic debate. It is a simple fact. Good political scientists should be cognisant of legal classifications, as listed in the law of the land, to produce cogent research with academic rigour.

Figure 1: Jats have been classified as OBC in Uttar Pradesh State List since 2000

Source: http://upsbcc.in/en/page/caste-inclusion-and-exclusion-cell-(accessed January 23, 2022)

Claim 2: Mehta’s biggest mistake is to focus on MPs. They are not important because they are not as influential

My response

Jaffrelot and Verniers say, ‘Mehta’s biggest mistake still lies elsewhere: to focus on MPs is not enough because parliamentarians are not as influential – since 2014. To study the composition of the Modi government is more important. Unfortunately, Modi ignores this site of power where upper-caste politicians staged a comeback in 2014 and even more in 2019.’

This is an astonishing claim on several counts.

• To seriously suggest that studying the social composition of Members of Parliament who get elected by the people in 543 constituencies nationwide in the world’s largest democracy is an assertion that beggars belief. It is also a claim that flies in the face of any robust academic logic – or plain common sense.

• I agree, of course, that studying BJP MPs alone, or those that got BJP tickets for the Lok Sabha, is not enough by itself and can only reflect at best a partial picture.

• This is precisely why the Mehta-Singh Social Index expanded the ambit of its social enquiry to five broad sites of power. To be clear, the Mehta-Singh Social Index is specific to Uttar Pradesh, a fact that is clearly asserted in The New BJP, where its findings are published, and in all extracts that have appeared of it, including on News 18. The Mehta-Singh Index studied the caste composition of:

o 2,560 Lok Sabha candidates fielded by the BJP, SP, Congress and BSP in each of UP’s 80 Lok Sabha constituencies and in every single national election over three decades (1991-2019).

o 1,612 Vidhan Sabha candidates fielded by the four parties in 403 Assembly constituencies in the state in the 2017 state election;

o 42 state-level BJP office-bearers in UP in 2020;

o 101 government ministers in UP, stretching across BJP chief minister Yogi Adityanath’s council of ministers (54) in 2020 and SP chief minister Akhilesh Yadav’s council of ministers (47) in 2012.

o 98 district-level BJP presidents in UP in 2020.

Where is the selective focus on only MPs from Uttar Pradesh?

• In fact, it is the other way round. It is Jaffrelot and Verniers, who in multiple published scholarly writings – both individually and jointly – have made the dubious claim of ‘the revenge of the upper castes’ after 2014, based solely on their analysis of data on Lok Sabha MPs from Ashoka University’s TCPD.

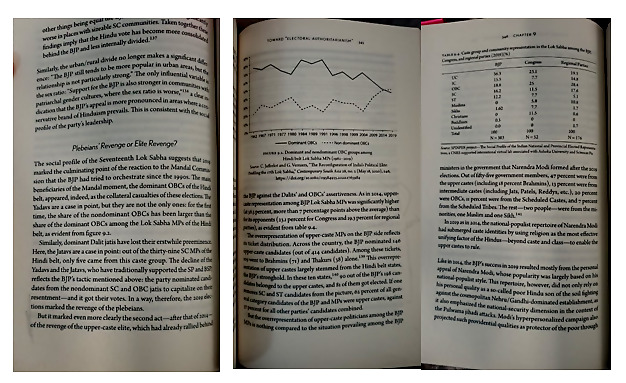

• Exhibit 1: Jaffrelot declared in his latest book Modi’s India that the 2019 poll marked ‘the revenge of the upper-caste elite,’ aligned with the ‘BJP against the Dalits’ and OBCs’ assertiveness’. He specifically based this statement on data on the caste of MPs in Parliament, published in the form of a chart along with these sentences (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Jaffrelot and Verniers claims based mainly on social analysis of MPs, but now say MPs not that important (Screengrabs from Modi’s India, pp. 344-346)

Source: Christophe Jaffrelot, Modi’s India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy (New Delhi: Context, 2021). Reproduced with permission from Context.

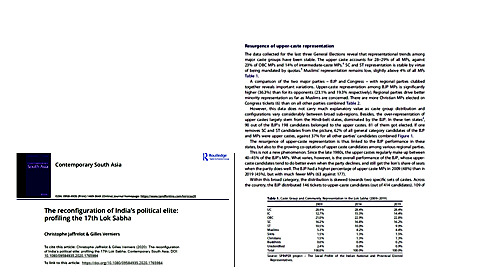

• Exhibit 2: Furthermore, Jaffrelot and Verniers have published entire peer-reviewed articles in global academic journals to make the claim of upper-caste dominance increasing in BJP structures, fundamentally based only on data-points and charts from the same research on MPs alone (see, for instance, Figure 3).

Figure 3: Jaffrelot and Verniers made same claim in an academic article based on analysis of MPs (Screengrabs from Contemporary South Asia, 2020)

Source: Gilles Verniers & Christophe Jaffrelot (2020), ‘The reconfiguration of India’s political elite: profiling the 17th Lok Sabha’, Contemporary South Asia, 28:2, pp. 242-254,

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09584935.2020.1765984

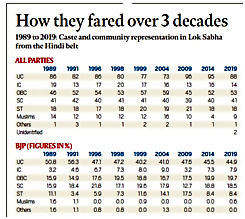

• Exhibit 3: In fact, they argued in an Indian Express article titled ‘In Hindi Heartland Upper Castes Dominate New Lok Sabha’ in May 2019 that ‘the last decade has seen the return of the savarn (upper caste) – and the erosion of OBC representation – along with the rise of the BJP. This trend started in 2009, but the Modi wave of 2014 has confirmed it and the last elections have resulted in a certain consolidation of this comeback to the pre-Mandal scenario.’ This was also based entirely on their analysis of the caste of MPs alone.

Figure 4: Jaffrelot and Verniers use MPs data to make wide claims but insist it is a mistake to focus on MPs (Screengrabs from The Indian Express, May 27, 2019)

Source: https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/in-hindi-heartland-upper-castes-dominate-new-house-5747511/

• In light of the above, for these scholars to now say that MPs are not important smacks of serious inconsistency.

Claim 3: Selective misquoting, wrongful misrepresentation on claims of resurgence of upper-castes in BJP MPs nationwide post-2014

Jaffrelot and Verniers claim that I wrongly compared Narendra Modi’s publicly announced caste composition of BJP’s total Lok Sabha MPs elected in 2019 – 113 (37.2 per cent) OBC, 43 (14.1 per cent) ST, 53 (17.4 per cent) SC – with their own analysis, which they say was based only on Hindi belt MPs. They go so far as to say that ‘he [Mehta] cites the data Modi gives regarding the BJP MPs in India as a whole, whereas the figures we give are for the Hindi belt only – and these two statistics are perfectly compatible!’

• The sheer dishonesty in claiming that Jaffrelot and Verniers’ findings from Ashoka University’s TCPD database were ‘perfectly compatible’ with Modi’s statistics is breathtaking.

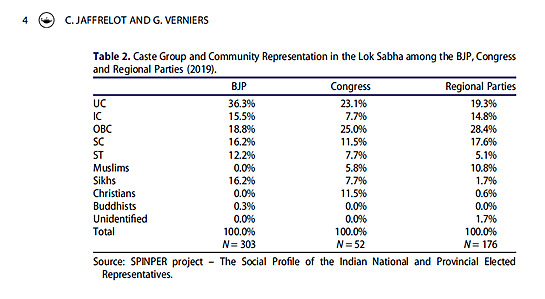

• Perhaps these scholars have forgotten that as recently as June 2020, they published a detailed academic article titled ‘The reconfiguration of India’s political elite: profiling the 17th Lok Sabha,’ where they published their analysis of all MPs nationwide in the current Lok Sabha. In this article, they specifically pegged the OBCs among BJP MPs nationwide at only 18.8 per cent. In other words, their calculation was half of Modi’s claim of 37.2 per cent OBC MPs in BJP nationally (see Figures 3 and 5).

My mathematics may be weak, but I fail to see how these two claims on OBC representation are statistically compatible. Perhaps, this screenshot of their own findings from this article may jog their memory.

Figure 5: How Jaffrelot and Verniers misrepresented their own previously published research in their response (A screenshot of their earlier findings on all MPs in current Lok Sabha in the journal Contemporary South Asia)

Source: Gilles Verniers & Christophe Jaffrelot (2020), ‘The reconfiguration of India’s political elite: profiling the 17th Lok Sabha’, Contemporary South Asia, 28:2, pp. 242-254

• While these scholars did mention the Hindi belt in this article, they also published nationwide data. ‘Across the country,’ they said, ‘the BJP distributed 146 tickets to upper-caste candidates (out of 414 candidates). 109 of these tickets went to Brahmins (71) and Thakurs (38) alone. The remaining tickets were distributed among 15 different groups.’ It is important to note that this article appeared in a special issue of this journal published by Taylor and Francis that both scholars themselves guest-edited.

• It was precisely because I found it impossible to square these two claims on OBC representation – by these scholars on the one hand and by PM Modi on the other – that I embarked on taking a revisionist look at caste in Uttar Pradesh and built the Mehta-Singh Social Index, with my colleague Sanjeev Singh, across several registers.

Claim 4: Mehta-Singh Index misleadingly represented data on Yogi Adityanath’s ministers to fit the argument

Jaffrelot and Verniers claim that the Mehta-Singh Index’s ‘data presentation here is clearly adjusted to fit the argument and that upper castes ‘occupy 48 per cent of all portfolios, while representing 20 per cent of UP’s population’.

• If these scholars had read my evidence as carefully as I have followed theirs, they would have realised that my assertion is very specific. Contrary to claims of an upper-caste resurgence in representation, what we have seen in Uttar Pradesh in the BJP is a massive resurgence of OBCs, wherein they became the most preponderant caste category represented in its power structures. The New BJP book clearly states that upper castes remained with the BJP but that the expansion of its voter base, its new MPs, MLAs and office-bearers was tilted in favour of OBCs.

• The comparison in this instance was specifically to the rise of OBCs compared to what came before – with the SP, which is the party of OBCs.

• In the case of ministers in Yogi Adityanath’s government, I specifically show that OBCs were the single highest category (35.1 per cent) – as juxtaposed with charges of Thakur domination (11.1 per cent). In fact, Brahmin ministers (18.5 per cent) outnumbered Thakur ones. So did SC ministers (12.9 per cent). Moreover, the percentage of OBC+SC ministers (48.1 per cent) was almost exactly the same as in Akhilesh Yadav’s preceding SP government (48.9 per cent) as did. This is a striking number when you consider that the BJP has always been seen as a party of upper castes, while the caste-based SP purports to be a party of social justice, and explicitly so in OBC terms. Significantly, Yogi Adityanath’s government has more OBC ministers proportionally (35.1 per cent) than Yadav’s (31.9 per cent). That was the true measure of the change, not generic upper caste vs other castes comparison.

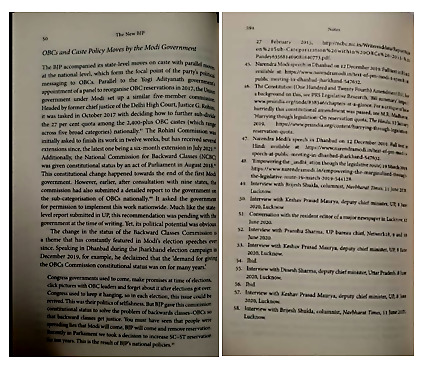

Claim 5: Wrongfully misquoting to say that ‘Mehta emphasises the fact that, at last, the Modi government has given the OBC Commission a constitutional status “to solve the problem of backwards classes” (p. 50).’

Finally, they have taken a direct quote from Prime Minister Narendra Modi, on page 50 of my book, and seem to attribute it to me! I simply reported a sequence of events on the Backward Classes Commission and the fact that this theme keeps recurring in PM Modi’s speeches. The quote in question – ‘to solve the problem of backwards classes’ – is clearly sourced on my book’s pages to a speech by Narendra Modi in Dhanbad on December 12, 2019 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: How Jaffrelot/Giles wrongly attribute a quote by PM Narendra Modi in The New BJP to Nalin Mehta

Source: Nalin Mehta, The New BJP: Modi and the Making of the World’s Largest Political Party, Westland Non-Fiction, 2022, pp. 50, 594

As a scholar, it is my job, of course, to always be open to any valid critique of a book that attempts to critically analyse an evolving organisation in a changing polity. If journalism is the first draft of history, then political science and political history have a deeper role to play in documenting what is happening in India. It is unfortunate that instead of looking at new evidence carefully and responding with reasoned evidence-based critique, respected scholars have resorted instead to shooting the messenger instead and stooping to demonstrable falsehoods.

Finally, the Mehta Singh Index in The New BJP documents in great detail how the BJP in Uttar Pradesh changed the nature of OBC representation in its organisational structures, party hierarchy and political leadership in government at multiple levels. My argument is specific to outlining this massive shift alone. Whether these structural moves since 2014 will translate into wider social changes or whether they are irreversible, remains an open question. Meanwhile, as the great British economist John Maynard Keynes reportedly once said, ‘When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, Sir?’

The author is Dean, School of Modern Media, UPES; Advisor, Global University Systems and Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. Mehta is the author of The New BJP: Modi and the Making of the World’s Largest Political Party, Westland Non-Fiction, 2022.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment