views

At 19, Subhankar Bhattacharya calls himself a “samarpit” (dedicated) activist of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). A descendant of a prosperous family from what is now Bangladesh, he has grown up on stories of affluence: large tracts of cultivable land, unadulterated milk, ghee, and other byproducts from their dairy farm, fresh fish from the large household pond, and respect for the family name that stems from more than a century of being part of the landed gentry.

Subhankar has been told and retold tales of what his grandparents had to leave behind in erstwhile East Bengal, which became East Pakistan after Partition and, subsequently, Bangladesh. The Sangh, which has been silently active in West Bengal since those days, has been moving like a ghost, like an invisible force, through the waves of refugees that made their way across the border in 1947, and then in 1971.

Madhusudan Kar, president of the Sangh’s South Kolkata district committee, said, “Hindutva was on top of everyone’s mind even after refugees migrated to West Bengal. The migrants looked for displaced Hindu families like themselves, which led them to the Sangh. The RSS was running a number of refugee camps to help Hindu families, which attracted many to the organisation. However, we believe more would have joined the Sangh back in 1947, and after, if it had the influence that it does now.”

Subhankar’s is not the only family that has stories to share of a forgotten prosperity that had to be forgone, while risking life and livelihood for safety from communal violence that left millions dead on both sides of the border.

Ask 79-year-old Gaurlal Pramanik, and he would share similar tales of misfortune and horror. Pramanik was only about five years old when his father and uncle managed to guide the whole family to safety. He still remembers looking out at the world from atop his father’s shoulders, as they walked from Krishnanagar to Barasat near Kolkata, a distance of over 80 kilometres.

The forgotten prosperity

Both Subhankar, who has just crossed the threshold to adulthood, and Gaurlal, 60 years his senior, believe there are problems with school history books – facts have not been presented the way they should be. Both are convinced that the political forces in power since Independence have not been truthful about certain aspects of modern Indian history, particularly when pitted against the testimonies of people like Subhankar’s grandparents or Gaurlal’s father and uncle, who were part of the single largest migration in human history in 1947.

They have also heard similar horror stories from friends and family, who moved to India later in 1971, when East Pakistan became Bangladesh. Both the septuagenarian and the young adult have grown up in an atmosphere where the nearby RSS shakhas played a crucial role in shaping their lives and thoughts. Bhattacharya, a student of computer applications, is representative of thousands of others with the same questions about more than three millennia of culture and practices, the Hindu identity, and nationalism.

It is this growing collection of people — mostly male, educated, from the upper social classes, and usually below 40 — that should have Mamata Banerjee, chief minister of West Bengal and Trinamool Congress (TMC) chairperson, worried. Not only are their numbers rising, most of them are of voting age and they are calling out the Trinamool Congress administration’s policy towards religious minorities as a blatant move of favouritism for electoral gains.

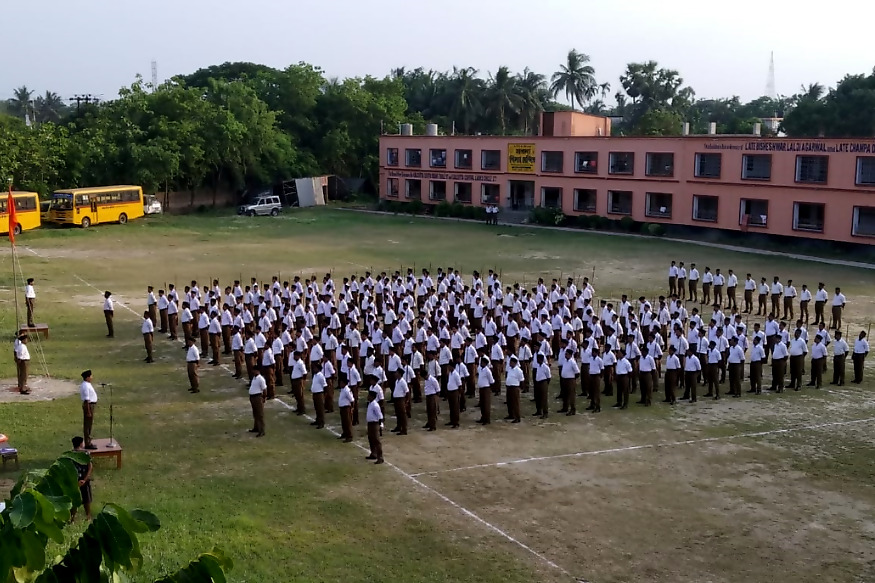

Growing numbers: An army on the move

Much to the chagrin of Mamata, the RSS kept its march through Bengal largely unseen until its pennant started showing up at unexpected places. With the aim to keep its flag flying high in a state where the ground is firm and ready for exploration, the Sangh has managed to expand its footprints substantially. While the number of shakhas or individual units – along with its members’ roster – has been a closely guarded secret for decades, a senior RSS functionary let slip that the number has gone up from 800 in 2011 to nearly 2,000 in 2018. Though the Sangh tries to distance itself from everyday politics, Mamata understands that the saffron brigade poses a serious threat to her party’s existence, given that the RSS mostly works among the people, a feat the TMC can only pull off if it can work out a way to ensure she’s omnipresent.

An influx of Bangladeshi immigrants has led to a jump in the number of Muslims in West Bengal, who form about 27 per cent of the population in the state. While Hindus remain a majority, their population share fell by 2.2 percentage points between the 2001 and 2011 census. The Sangh and Bharatiya Janata Party have managed to use this as a spectre to stir up dread among a section of the state’s Hindus and win their support. Politics in Bengal has slipped into lawlessness, with frequent clashes between TMC and RSS-BJP workers, each blaming the other for the instigation. Religious events, cultural practices and even food habits are in the eye of the storm.

Despite being the home state of Jana Sangh ideologue Syama Prasad Mukherjee, the RSS was hardly a factor worthy of notice in Bengal for decades. Since the near-absolute rout of the CPI (M)-led Left Front and Narendra Modi’s ascent to power in 2014, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh has suddenly emerged as a force to reckon with in the state. So much so that veteran journalists, who have covered politics for years, are getting into the habit of making rounds of Keshav Bhavan in north Kolkata, a nondescript building that houses the Sangh’s regional headquarters. Even till a couple of years ago, most reporters would have walked past the structure without a second glance.

Behind the saffron veil

The growing media glare has not changed things much for the RSS and it continues to run its show the way it always has, away from the public eye. The Sangh has carefully draped its saffron veil over all its activities, be it organising workshops or top Sangh functionaries addressing frequent seminars at Salt Lake Sector V, Bengal’s IT hub. Even though the practice is to run workshops spanning over 15 to 20 days as part of karyakarta nirmaan, an initiation process to train new cadres, such sessions have hardly ever drawn any attention.

It is only when rich and powerful influencers and well-wishers from the city sometimes drop by on special occasions that one might spot a fleet of top-end cars like Audi, BMW, and Mercedes-Benz parked outside such a camp. These gatherings are not only rare, but also very well-managed. The draw of the RSS for a large section of Hindus is apparent from the profile of the participants, including doctors, lawyers, engineers, and even secondary-level students.

Kar said that a sizeable number of refugees initially moved towards the Left because the red brigade provided them with land, jobs and security: not because of ideological reasons but because the communists were able to implement policies well that helped the displaced people in their fight for survival. “Most people were looking for security from violence and instability, which the Sangh provided them since then. Hindus were unified under the Sangh’s banner,” he added.

Kapil Thakur belongs to the Matua community and is a senior CPI (M) leader. He represented the group, which is a sizeable electorate of around 4.5 lakh people, all migrants from then East Pakistan. They settled at Thakurnagar in North 24 Parganas district and have been a moving force in Bengal for many years. Since they sided once with Mamata (around a decade back) and now divided (as a significant number went to the BJP), the Matua community has had three MPs (TMC’s Sunil Mondal at Purba Bardhaman, BJP’s Shantanu Thakur at Bongaon and BJP’s Jagannath Sarkar at Ranaghat) apart from several MLAs and remains an influence on the lower caste and migrant Hindu votes in several parts of the state.

The swing from Left to Right

Talking about the refugee crisis and how they have been caught between the Left and the Right, Thakur explained that most refugee camps in Bengal had a Leftist influence since many of these sites were led by communist leaders, who were otherwise involved with agrarian movements in what is now Bangladesh.

“Most refugee movements in Kolkata and rest of Bengal had Left leaders because due to some policies of the Nehru administration and subsequent Congress governments, particularly the Bengali refugees had lost faith in the Congress and moved towards the Left. After the Left Front came to power in 1977, this was further solidified as the government in Bengal made special provisions for refugees,” he said. Thakur is of the belief that while refugee communities sided with the Trinamool Congress after the Left had lost their confidence, the RSS was never a major mover and shaker with Bengalis.

Rabindranath Ghosh, former Trinamool Congress MP from Cooch Behar, pointed out how thousands fled from East Pakistan to West Bengal during bloody riots in 1950-52, as also during the 1971 India-Pakistan war. “RSS campaigns on the basis of religion, saying ‘since you are from Bangladesh, you were forced to come here because of Muslim aggression’. Even though their logic is fallacious, some people are agreeing with it and joining the Sangh or supporting the BJP. The saffron brigade is not in power because of its performance or ideology but because of the malicious religious campaign it is running,” he said.

Ghosh pointed out that political parties with a national footprint, like the Congress, have failed to combat the “malicious” campaign the saffron camp has been running. However, the RSS seems to be losing its grip over the BJP and the overall saffron presence. “Look at the candidates fielded by BJP this election and you will find that most of them are not backed by the Sangh, and are people with almost no connect with the saffron ideology. It clearly shows that their core ideology is getting diluted and the BJP is merely trying to fill up its ranks with any means necessary,” he said.

State surveillance and other challenges

Talking about challenges beyond the realm of awareness, Biplab Roy, pranta prachar pramukh, or the Sangh’s regional head, pointed out that due to “prolonged negative campaign against the organisation” the cadres have always faced resistance when they first arrived in an area to work on local development. He cited as example a number of venues of their recent workshops, the land for which was bought in the 1980s. Many of these are Muslim-majority areas and the Sangh faced resistance from residents. “But we stood our ground and we have not faced any problems since then,” said Debashis Chowdhury, an RSS leader.

Roy explained that unlike in some other states, in West Bengal political awareness is high even among the rural populace. “People here generally side with the party in power looking at the ease of getting things done. Under such circumstances, it gets difficult to make people understand that there is value in having groups like ours on their side because we only look at long-term solutions, not just immediate measure like the existing political class,” he said.

The senior RSS functionaries added that constant surveillance by the administration is another major challenge they have to face in states like West Bengal, where the ruling party is wary of the Sangh’s activities. “Years of campaign against us have made it easier for our opponents to keep an eye on us in the name of secularism. It has intensified since the ruling party is following a policy of minority appeasement. But eventually we get over all such hurdles. Even local residents, many of whom are Muslims, come around and stand by us when they realise our dedication to nation-building,” Roy said.

Old hand, new guard: A Sangh man salvages Bengal BJP

Senior RSS functionaries in the state admit that the winds of change have started to blow, particularly since Modi came to power in 2014. Even in West Bengal, ‘RSS’ is not a taboo word anymore and people are openly talking about the need to have the Sangh in the face of “growing minority appeasement”. Even the state BJP, which was not even a marginal force here, has started claiming bigger stakes in the political arena and has significantly improved its electoral prospects. Things changed even more with the arrival of Dilip Ghosh in the frame when he took over as president of the state BJP unit in late 2014. An old RSS hand, with around 25 years of field experience in the East and the Northeast, he was brought in to infuse fresh ideas into the party’s state unit.

In Ghosh’s own words: “Whatever I am today is because of the RSS. The Sangh teaches one how to live a disciplined life and it is this training that gave me the strength to take up the role of the state BJP chief. RSS builds the right kind of men for our country, our mantra being ‘sound mind in sound body’. I am proud to be an RSS man and even today I follow the daily practice of the Sangh just like I did as a young cadre.”

“RSS is a powerhouse, but doesn’t call the shots”

The proximity of the BJP leadership to the Sangh has often raised questions in the face of criticism that the party is just the political facade of the RSS, a conclusion that has been objectively countered by both BJP and RSS leaders. Sangh functionaries have repeatedly claimed that they are just a socio-cultural organisation with no political ambitions, even though on several occasions it has become apparent that the RSS is much more than just an ally for the BJP and that its Nagpur headquarters has more pull in the country’s ruling party than they let out.

Roy admitted that the RSS is more of a mother ship to the BJP – which functions like its political wing – but he denied that the Sangh pulls the strings. “RSS is a powerhouse but not a puppeteer. Those who join the Sangh get trained and walk out into the world, have the freedom to choose their own avenues, be it joining politics, cow conservation research, or labour union. We don’t impose anything on anyone but give them the options to choose freely,” he said.

And the recent return of Ram Lal, after 13 years as the BJP’s general secretary (organisation), who is now co-incharge of the RSS’s publicity and communications wing, is another milestone.

The soaring flag: More than just a triangle

The saffron triangle freely flies high atop every RSS unit, reminiscent of a past when Hindu rulers displayed similar pennants on their chariots and forts, all the way back to the days of the Mahabharata. Like every realm, the Sangh, which is a realm unto itself, gives due importance and dignity to its flag and has specific rituals to be followed.

The flag is hoisted every day at the break of dawn and taken down at dusk, ensuring a night of well-earned rest. According to Roy, the Sangh flag comes right after Bharat Mata, the motherland in deity form, in terms of its sacred nature, and any affront to the flag is dealt with in a swift and stern manner. “The flag is the heart of our operations. It’s our honour and dignity. It is an entity unto itself,” he said.

Comments

0 comment