views

Forming Equivalent Fractions

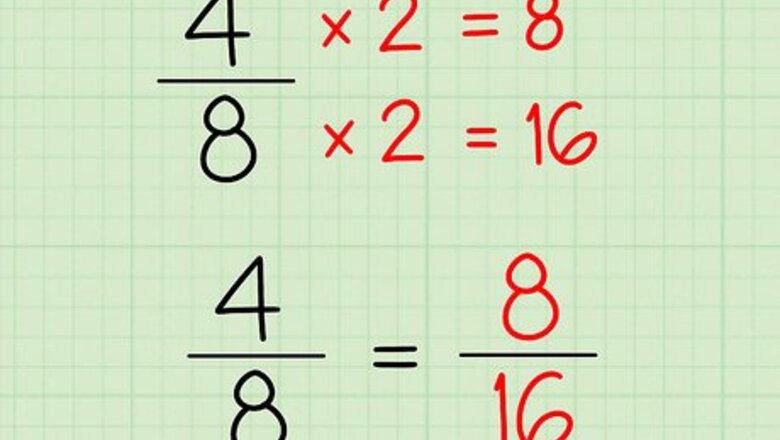

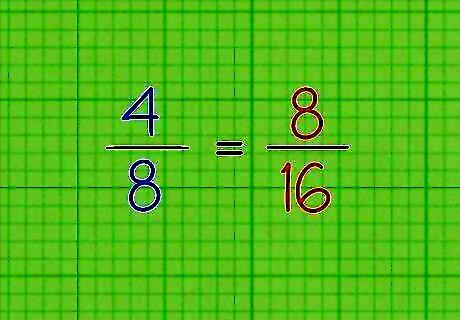

Multiply the numerator and denominator by the same number. Two fractions that are different but equivalent have, by definition, numerators and denominators that are multiples of each other. In other words, multiplying the numerator and denominator of a fraction by the same number will produce an equivalent fraction. Though the numbers in the new fraction will be different, the fractions will have the same value. For instance, if we take the fraction 4/8 and multiply both the numerator and denominator by 2, we get (4×2)/(8×2) = 8/16. These two fractions are equivalent. (4×2)/(8×2) is essentially the same as 4/8 × 2/2 Remember that when multiplying two fractions, we multiply across, meaning numerator to numerator and denominator to denominator. Notice that 2/2 equals 1 when you carry out the division. Thus, it's easy to see why 4/8 and 8/16 are equivalent since multiplying 4/8 × (2/2) = 4/8 still. The same way it’s fair to say that 4/8 = 8/16. Any given fraction has an infinite number of equivalent fractions. You can multiply the numerator and denominator by any whole number, no matter how large or small to obtain an equivalent fraction.

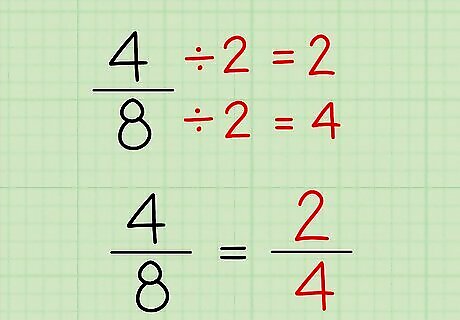

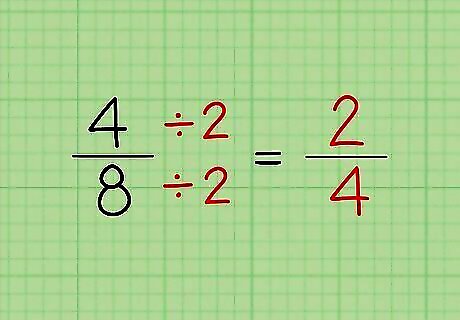

Divide the numerator and denominator by the same number. Like multiplication, division can also be used to find a new fraction that's equivalent to your starting fraction. Simply divide the numerator and the denominator of a fraction by the same number to obtain an equivalent fraction. There is one caveat to this process--the resulting fraction must have whole numbers in both the numerator and denominator to be valid. For instance, let's look at 4/8 again. If, instead of multiplying, we divide both the numerator and denominator by 2, we get (4 ÷ 2)/(8 ÷ 2) = 2/4. 2 and 4 are both whole numbers, so this equivalent fraction is valid.

Using Basic Multiplication to Determine Equivalency

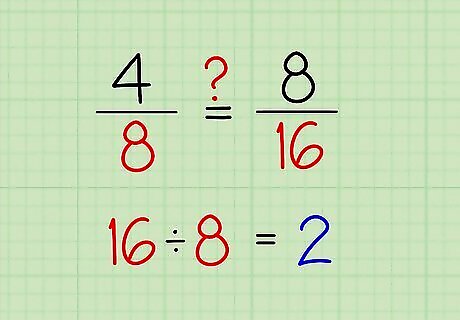

Find the number by which the smaller denominator needs to be multiplied to make the larger denominator. Many problems regarding fractions involve determining if two fractions are equivalent. By calculating this number, you can begin putting the fractions in the same terms to determine equivalency. For example, take the fractions 4/8 and 8/16 again. The smaller denominator is 8, and we would have to multiply that number x2 in order to make the larger denominator, which is 16. Therefore, the number in this case is 2. For more difficult numbers, you can simply divide the larger denominator by the smaller denominator. In this case 16 divided by 8, which still gets us 2. The number may not always be a whole number. For example, if the denominators were 2 and 7, then the number would be 3.5.

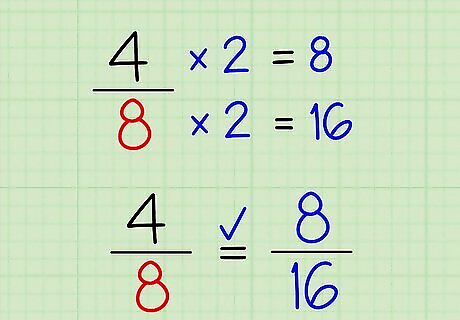

Multiply the numerator and denominator of the fraction expressed in lower terms by the number from the first step. Two fractions that are different but equivalent have, by definition, numerators and denominators that are multiples of each other. In other words, multiplying the numerator and denominator of a fraction by the same number will produce an equivalent fraction. Though the numbers in this new fraction will be different, the fractions will have the same value. For instance, if we take the fraction 4/8 from step one and multiply both the numerator and denominator by our previously determined number 2, we get (4×2)/(8×2) = 8/16. Thus proving that these two fractions are equivalent.

Using Basic Division to Determine Equivalency

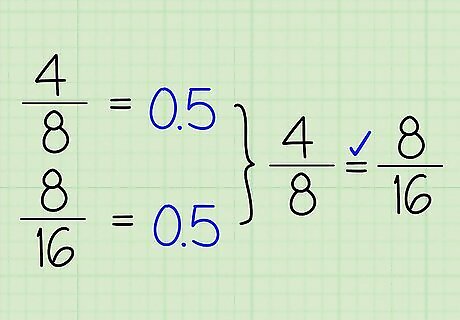

Calculate each fraction as a decimal number. For simple fractions without variables, you can simply express each fraction as a decimal number to determine equivalency. Since every fraction is actually a division problem to begin with, this is the simplest way to determine equivalency. For instance, take our previously used 4/8. The fraction 4/8 is equivalent to saying 4 divided by 8, which 4/8 = 0.5. You can solve for the other example as well, which is 8/16 = 0.5. Regardless of the terms of a fraction, they are equivalent if the two numbers are exactly the same when expressed as a decimal. Remember that the decimal expression may go several digits before the lack of equivalence becomes apparent. As a basic example, 1/3 = 0.333 repeating while 3/10 = 0.3. By using more than one digit, we see that these two fractions are not equivalent.

Divide the numerator and denominator of a fraction by the same number to get an equivalent fraction. For more complex fractions, the division method requires additional steps. As with the multiplication method, you can divide the numerator and the denominator of a fraction by the same number to obtain an equivalent fraction. There is one caveat to this process. The resulting fraction must have whole numbers in both the numerator and denominator to be valid. For instance, let's look at 4/8 again. If, instead of multiplying, we divide both the numerator and denominator by 2, we get (4 ÷ 2)/(8 ÷ 2) = 2/4. 2 and 4 are both whole numbers, so this equivalent fraction is valid.

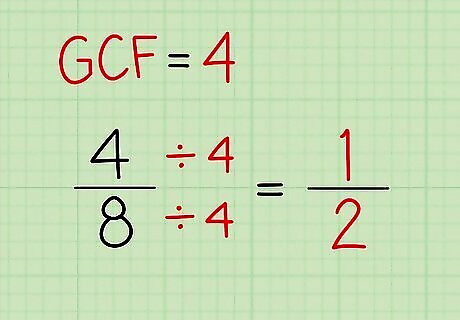

Reduce the fractions to their lowest terms. Most fractions should typically be expressed in their lowest terms, and you can convert fractions to their simplest terms by dividing by their greatest common factor (GCF). This step operates by the same logic of expressing equivalent fractions by converting them to have the same denominator, but this method seeks to reduce each fraction to its lowest expressible terms. When a fraction is in its simplest terms, its numerator and denominator are both as small as they can be. Neither can be divided by the any whole number to obtain anything smaller. To convert a fraction that's not in simplest terms to an equivalent form that is, we divide the numerator and denominator by their greatest common factor. The greatest common factor (GCF) of the numerator and denominator is the largest number that divides into both to give a whole number result. So, in our 4/8 example, since 4 is the largest number that divides evenly into both 4 and 8, we would divide the numerator and denominator of our fraction by 4 to get it in simplest terms. (4 ÷ 4)/(8 ÷ 4) = 1/2. For our other example of 8/16, the GCF is 8, which also results in 1/2 as the simplest expression of the fraction. EXPERT TIP Joseph Meyer Joseph Meyer Math Teacher Joseph Meyer is a High School Math Teacher based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He is an educator at City Charter High School, where he has been teaching for over 7 years. Joseph is also the founder of Sandbox Math, an online learning community dedicated to helping students succeed in Algebra. His site is set apart by its focus on fostering genuine comprehension through step-by-step understanding (instead of just getting the correct final answer), enabling learners to identify and overcome misunderstandings and confidently take on any test they face. He received his MA in Physics from Case Western Reserve University and his BA in Physics from Baldwin Wallace University. Joseph Meyer Joseph Meyer Math Teacher Simplifying a fraction just changes the way the fraction is written. To simplify a fraction, you can cancel out the greatest common factor from the numerator and denominator or convert an improper fraction to a mixed number. This doesn't change the inherent value of the fraction.

Using Cross Multiplication to Solve for a Variable

Set the two fractions equal to one another. We use cross multiplication for math problems where we know the fractions are equivalent, but one of the numbers has been replaced with a variable (typically x) for which we must solve. In cases like this, we know these fractions are equivalent because they're the sole terms on opposite sides of an equal sign, but it's often not obvious how to solve for the variable. Luckily, with cross multiplication, solving these types of problems is easy.

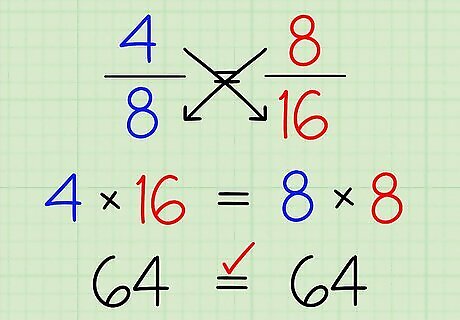

Take the two equivalent fractions and multiply across the equals sign in an "X" shape. In other words, you multiply the numerator of one fraction by the denominator of the other and vice versa, then set these two answers equal to each other and solve. Take our two examples of 4/8 and 8/16. These two don't contain a variable, but we can prove the concept since we already know they're equivalent. By cross multiplying, we get 4 x 16 = 8 x 8, or 64 = 64, which is obviously true. If the two numbers are not the same, then the fractions are not equivalent.

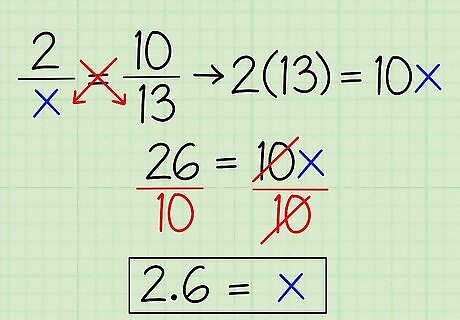

Introduce a variable. Since cross multiplication is the easiest way to determine equivalent fractions when you must solve for a variable, let's add a variable. For example, let's consider the equation 2/x = 10/13. To cross multiply, we multiply 2 by 13 and 10 by x, then set our answers equal to each other: 2 × 13 = 26 10 × x = 10x 10x = 26. From here, getting an answer for our variable is a matter of simple algebra. x = 26/10 = 2.6, making the initial equivalent fractions 2/2.6 = 10/13.

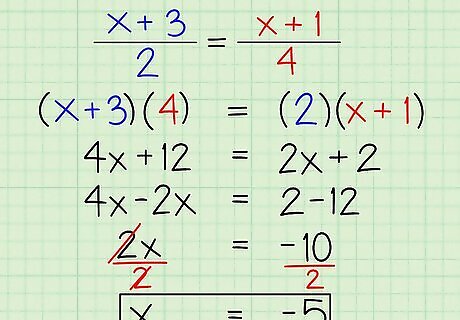

Use cross multiplication for equations with multiple variables or variable expressions. One of the best things about cross multiplication is that it works in essentially the same way whether you're dealing with two simple fractions (as above) or with more complex fractions. For instance, if both fractions contain variables, you just have to eliminate these variables at the end during the solving process. Similarly, if the numerators or denominators of your fractions contain variable expressions (such as x + 1), simply "multiply through"by using the distributive property and solve as you normally would. For instance, let's consider the equation ((x + 3)/2) = ((x + 1)/4). In this case, as above, we'll solve by cross multiplying: (x + 3) × 4 = 4x + 12 (x + 1) × 2 = 2x + 2 2x + 2 = 4x + 12, then we can simplify the equation by subtracting 2x from both sides 2 = 2x + 12, then we should isolate the variable by subtracting 12 from both sides -10 = 2x, and divide by 2 to solve for x -5 = x

Using the Quadratic Formula to Solve for Variables

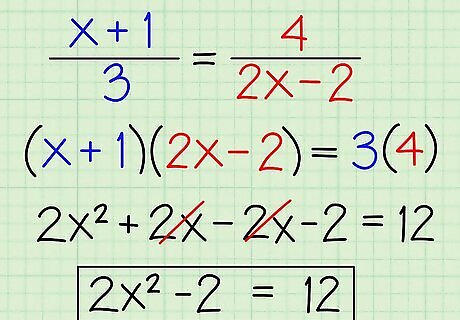

Cross multiply the two fractions. For equivalency problems that require the quadratic formula, we still begin by using cross multiplication. However, any cross multiplication that involves multiplying variable terms by other variable terms is likely to result in an expression that can't easily be solved via algebra. In cases like these, you may need to use techniques like factoring and/or the Quadratic Formula. For example, let's look at the equation ((x +1)/3) = (4/(2x - 2)). First, let's cross multiply: (x + 1) × (2x - 2) = 2x + 2x -2x - 2 = 2x - 2 4 × 3 = 12 2x - 2 = 12.

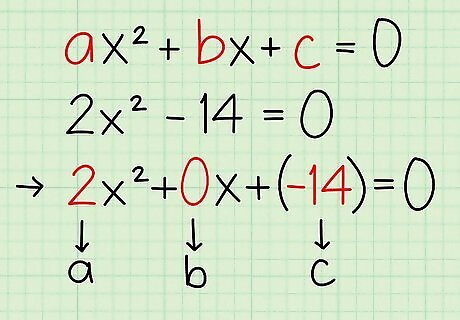

Express the equation as a quadratic equation. At this point, we want to express this equation in quadratic form (ax + bx + c = 0), which we do by setting the equation equal to zero. In this case, we subtract 12 from both sides to get 2x - 14 = 0. Some values may equal 0. Though 2x - 14 = 0 is the simplest form of our equation, the true quadratic equation is 2x + 0x + (-14) = 0. It will probably help early on to mirror the form of the quadratic equation even when some values are 0.

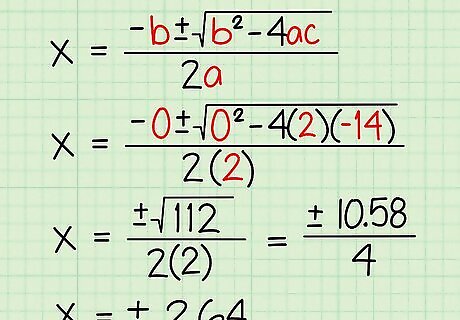

Solve by plugging the numbers from your quadratic equation into the quadratic formula. The quadratic formula (x = (-b +/- √(b - 4ac))/2a) will help us solve for our value x at this point. Don’t be intimidated by the length of the formula. You’re simply taking the values from your quadratic equation in step two and plugging them into the appropriate spots before solving. x = (-b +/- √(b - 4ac))/2a. In our equation, 2x - 14 = 0, a = 2, b = 0, and c = -14. x = (-0 +/- √(0 - 4(2)(-14)))/2(2) x = (+/- √( 0 - -112))/2(2) x = (+/- √(112))/2(2) x = (+/- 10.58/4) x = +/- 2.64

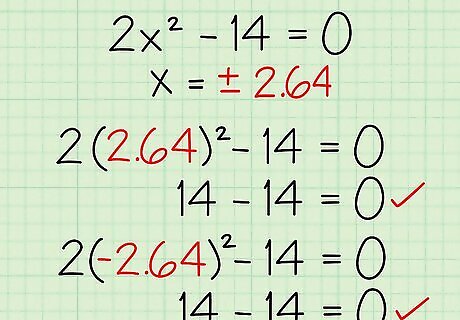

Check your answer by plugging the x value back into your quadratic equation. By plugging the calculated value of x back into your quadratic equation from step two, you can easily determine if you reached the correct answer. In this example, you would plug both 2.64 and -2.64 into the original quadratic equation.

Comments

0 comment