views

It is one of the most awaited films of the year and a Hindi film superstar, Ajay Devgn, appears in it for mere 15 minutes. A role he didn’t hesitate to sign on once the director told him about it. That is the power of one of the biggest directors in India currently, S.S. Rajamouli, whose Baahubali: The Beginning (2015) alerted Bollywood to its imminent demolition. Since then, the success of Baahubali 2: The Conclusion (2017) and KGF: Chapter 1 (2018), a COVID-induced lockdown on box office revenue, the emergence of streaming platforms and Bollywood’s confused narrative have ensured the rise of the Southern film industry.

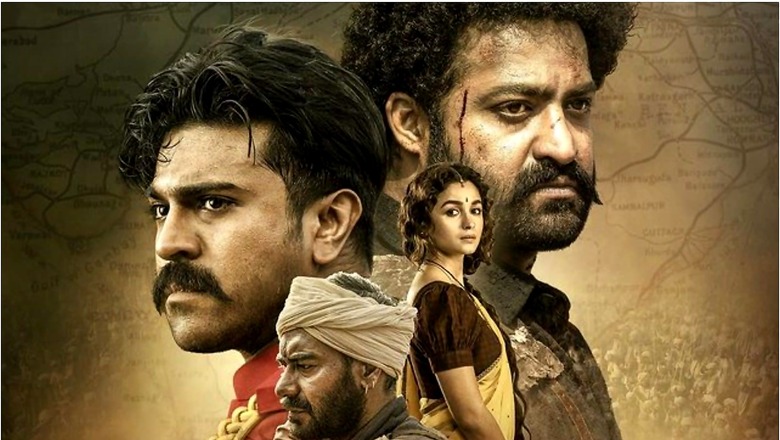

The Bollywood movie, once the big brother, is slowly finding itself giving way to the pan-Indian film, like Rajamouli’s RRR, with star casts drawn from across the country and stories born of the hinterland. No longer is each industry happy to spiral away in its own orbit. Paths are crossing and sparks are flying.

About time too. Hindi films have always borrowed storylines from Southern films and vice-versa. Starting from Mani Ratnam’s blockbusters such as Nayakan (1987), Roja (1992) and Bombay (1995), which were simultaneously made in multiple languages (Tamil, Telugu and Hindi), Tamil movies tried to break into the Hindi-speaking market. Multilingual productions became more common and made financial sense within the South Indian film industry, though they remained almost non-existent in Bollywood.

The Southern film industry expanded the national imagination, adding greater diversity, new stories and new ways of being Indian, points out film scholar Selvaraj Velayutham. Bollywood started to seem fake, out-of-touch, and spoke to a narrowly defined pan-Indianness, which was restricted to the North.

But like A.R. Rahman’s music, or S.P. Balasubrahmanyam’s song, it could not be denied for long. Baahubali opened the floodgates for a new kind of filmmaking where Malayalam actor Fahadh Faasil can play a diabolical police officer, Bhanwar Singh Shekhawat, in Pushpa: The Rise, the latest Telugu potboiler about red sandalwood smugglers, and Tamil superstar Dhanush can be the sensitive Tamilian doctor Vishu in love with a young woman from Bihar in Aanand L. Rai’s Atrangi Re. The country is no longer unitary, why should its pop culture not reflect it? As young people move across regions for work and love, different dialects and different faces are audible and visible.

For the first time, the Indian film industry is poised to realise its full potential, as it should. After all, if the Indian film industry’s gross annual box office revenue pre-pandemic was Rs 12,000 crore, other languages have to be acknowledged too. Bollywood is Rs 6,000 crore of the total box office revenue, Hollywood Rs 1,500 crore, the Southern film industry is at Rs 3,600 crore (Rs 1500 crore each for Tamil and Telugu, and Rs 300 crore for Malayalam and Kannada). Other regional cinemas such as Marathi, Bhojpuri and Bengali comprise the remaining Rs 900 crore of the total revenue pie.

“Language is just a medium of communication. In films, we communicate with the audience through images. I have always believed that if a story has the right emotion, like the mother finding the long-lost son, the language absolutely doesn’t matter. You connect to the emotion,” says Rajamouli.

“When we finish the story, we see whether it is universal or regional in nature. You can’t force it. The story decides itself. How much you put your trust in the emotions is what matters,” he adds.

The actors agree. Telugu star Allu Sirish says at least for big-budget filmmaking, pan-India films will be the way forward. “Only big films can get a theatrical release across markets. But other smaller films have a shot at pan-India audience as well. My own film Okka Kshanam got dubbed in Hindi, Tamil and Malayalam on satellite and OTT. It did well in all markets,” he says. So he now tells his directors, “Remember we’re not making films only for Telugu audience anymore, we’re making pan-India films in Telugu.”

So what is driving the inter-casting and the inter-directing? Art or commerce? Or both? Actors are working across languages — an example is the way Alia Bhatt sought out Rajamouli for a role in RRR. Says Sirish: “Such casting makes the film more relatable to the Hindi audience (art) and increases the market value (commerce).”

The condescension has lessened. Earlier, if an actor in Hindi films worked in the South, it usually meant that their career in Bollywood was over. Also if Southern filmmakers wanted a Bollywood technician, they would quote unreasonable amount as a premium to work in a “regional film”. Today that’s not the case. It’s seen as a respectable career move. Earlier, says Sirish, “we would hardly get any casting calls from Hindi filmmakers. But today for various roles in Hindi projects, a lot of us, Southern actors, are being approached.”

So Nayanthara is starring alongside Shah Rukh Khan in Atlee’s untitled movie, while Prabhas is Kriti Sanon’s hero in Om Raut’s Adipurush. Alia Bhatt can take recommendations on Malayalam films to watch from her co-star Roshan Mathew in her first film production, Darlings, while Raveena Tandon can play her part in KGF: Chapter 2 with as much gusto as she approaches her lead role in the Netflix thriller Aranyak. The distance traversed by the ascending stars in the pan-Indian film will go beyond Mumbai’s Juhu-Andheri-Lokhandwala.

The author is a senior journalist and former editor of India Today magazine. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment