views

After a drastic decline this spring, global greenhouse gas emissions are now rebounding sharply, scientists reported, as countries relax their coronavirus lockdowns and traffic surges back onto roads. It’s a stark reminder that, even as the pandemic rages, the world is still far from getting global warming under control.

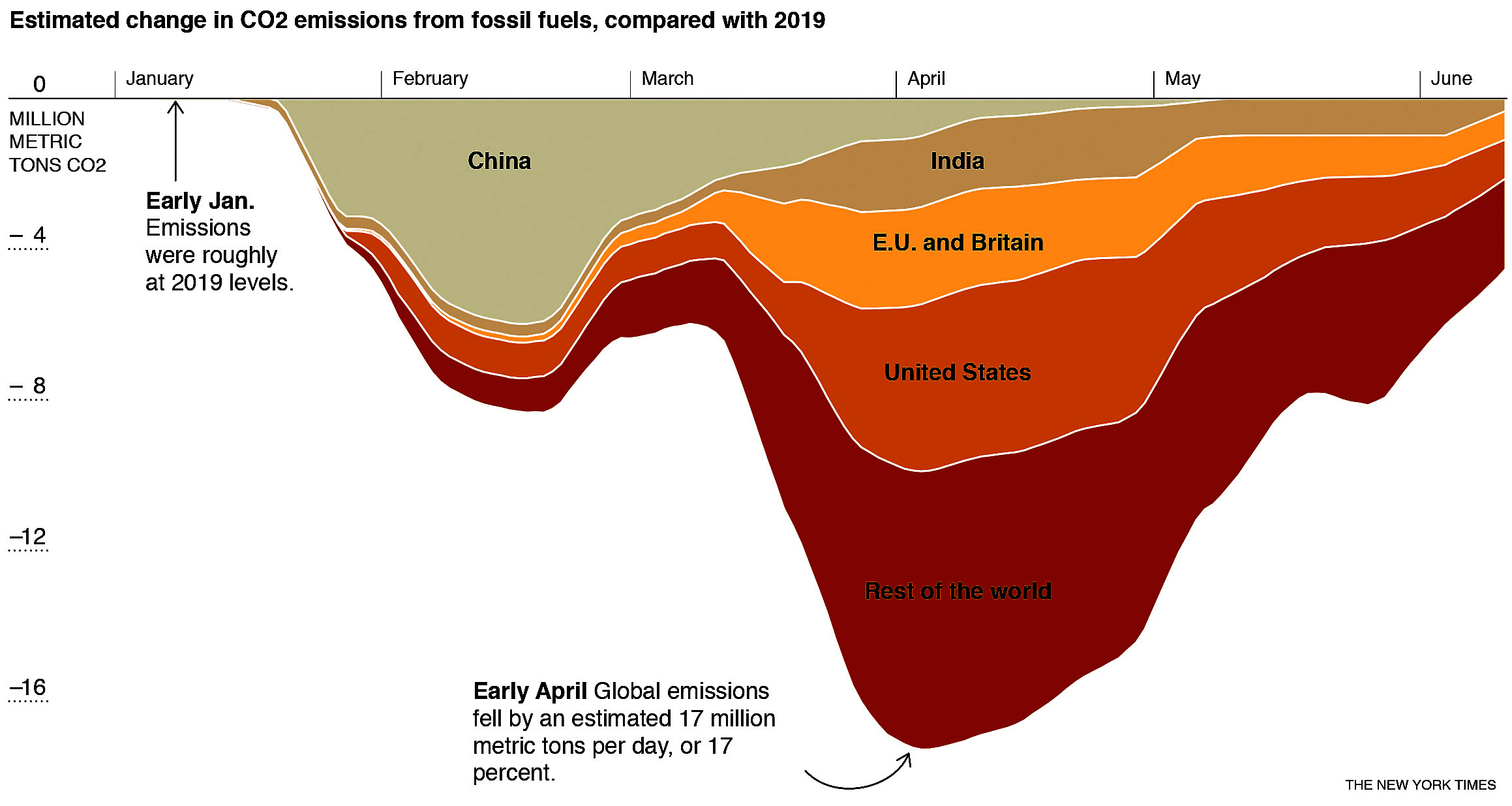

In early April, daily fossil fuel emissions worldwide were roughly 17% lower than they were in 2019, as governments ordered people to stay home, employees stopped driving to work, factories idled, and airlines grounded their flights, according to a study published in May in Nature Climate Change.

But by mid-June, as countries eased their lockdowns, emissions had ticked up to just 5% below the 2019 average, the authors estimated in a recent update. Emissions in China, which accounts for one-quarter of the world’s carbon pollution, appear to have returned to pre-pandemic levels.

The study’s authors said they were surprised by how quickly emissions had rebounded. But, they added, any drop in fossil fuel use related to the coronavirus was always likely to be temporary unless countries took concerted action to clean up their energy systems and vehicle fleets as they moved to rebuild their ailing economies.

“We still have the same cars, the same power plants, the same industries that we had before the pandemic,” said Corinne Le Quéré, a climate scientist at the University of East Anglia in England and lead author of the analysis. “Without big structural changes, emissions are likely to come back.”

At the peak of the lockdowns, vehicle traffic fell by roughly half in places like Europe and the United States, a big reason that emissions dropped so rapidly. But in many cities, cars and trucks are now returning to the roads, even if overall traffic remains below pre-pandemic levels. Although many people continue to work from home, there are also early signs that people are avoiding public transportation for fear of contracting the virus and driving instead.

In the United States, electricity demand had inched back closer to 2019 levels by June after a steep decline in the spring. But that didn’t mean that the economy has fully recovered, said Steve Cicala, an economics professor at the University of Chicago who has been tracking electricity data. One factor may be that people are running their personal air conditioners more often during hot weather as they stay at home.

Even with the recent rebound in emissions, it is clear the global economy is still reeling from the virus. Surface transportation, air travel and industrial activity remain down, and the world is consuming less oil, gas and coal than a year ago. And the pandemic is far from over: Cases continue to rise worldwide, and some countries could end up reimposing stricter lockdown measures. On Monday, Chinese officials urged residents in Beijing to stay at home after a fresh cluster of cases emerged in a local market.

The researchers estimated that global fossil-fuel emissions for all of 2020 are likely to be 4% to 7% lower than in 2019. If that prediction holds, it would be several times larger than the decline seen in 2009 after the global financial crisis.

“A 5% change in global emissions is enormous; we haven’t seen a drop like that since at least World War II,” said Rob Jackson, an Earth scientist at Stanford and a co-author of the study. But, he added, it’s still just a fraction of the decline needed to halt global warming, which would require bringing global emissions all the way down to nearly zero.

Ultimately, climate experts said, the trajectory of global emissions in the years ahead is likely to be heavily influenced by the stimulus measures that countries enact as they seek to revive their economies. Environmentalists have called on governments to invest in cleaner energy sources in order to prevent a large rebound in fossil fuel use.

So far, plans from the three biggest producers of greenhouse gases have been mixed. In May, European Union policymakers proposed an $826 billion recovery package aimed at transitioning the continent away from fossil fuels by expanding wind and solar power, retrofitting old buildings and investing in cleaner fuels, like hydrogen.

But China has sent conflicting signals, approving the construction of new coal plants while also expanding incentives for electric vehicles. And in the United States, the Trump administration has continued to roll back environmental rules during the outbreak.

Some cities are trying to avoid a crush of vehicle traffic as the lockdowns end. Paris and Milan are adding miles of new bike lanes. London has increased congestion charges on cars traveling into the city at peak hours. Officials in Berlin have discussed requiring residents to buy bus passes in order to make car travel less attractive. But those efforts are still far from universal.

“Europe looks like the major exception so far,” said David Victor, a professor of international relations at the University of California. “Many governments are scrambling to recover economically and not paying as much attention to the environment.”

Victor co-authored a recent analysis in Nature estimating that a major push toward a “green” recovery by world governments could reduce carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere by up to 19 parts per million by midcentury compared with a recovery that emphasized fossil fuels. The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has already increased by more than 127 ppm since preindustrial times, raising the average global temperature roughly 1 degree Celsius, or 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit.

Scientists still don’t have a reliable system for measuring day-to-day changes in human emissions of carbon dioxide, the main driver of global warming. For the Nature Climate Change study, the researchers looked at a variety of metrics — such as electricity demand in the United States and Europe, industrial activity in China and traffic measurements in cities around the world — and measured how they changed in response to lockdowns. They then extrapolated these shifts to smaller countries where data is sparser, making assumptions about how emissions were likely to change.

The authors cautioned that these estimates still have large uncertainties, although their findings broadly aligned with a separate analysis from the International Energy Agency, which also tried to calculate the drop in emissions during the pandemic based on declines in coal, oil and natural gas use.

Brad Plumer and Nadja Popovich c.2020 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment