views

Deciding the End

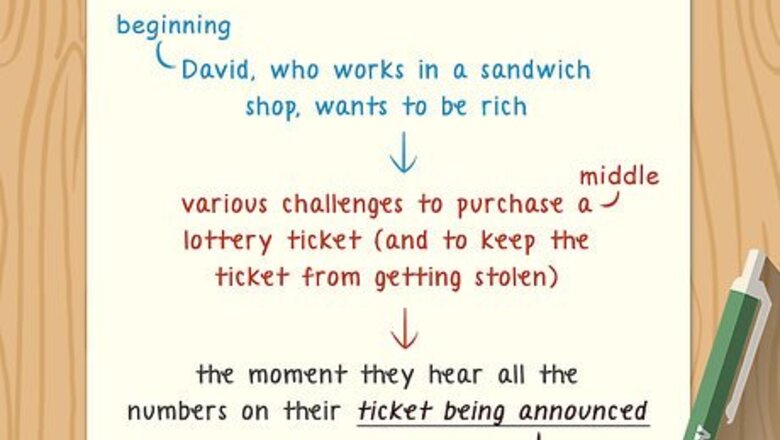

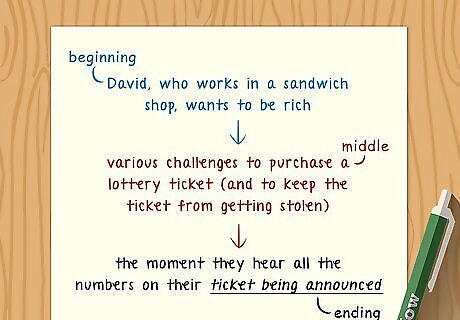

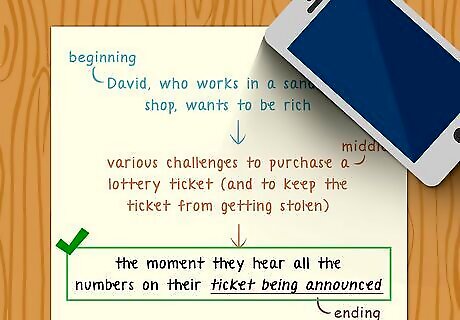

Identify the parts of your story. Your story will have a beginning that introduces your characters, setting, and conflict. The middle of the story will include rising tension, complications, and your characters' reactions to the conflict. Finally, the end will detail the resolution of your conflict and the aftermath. Your ending should come when the main character reaches or fails to reach their goal For example, if your character wants to be rich, they could go through various challenges in order to buy a lottery ticket. Do they succeed? If so, end with the moment they hear all the numbers on their ticket being announced.

Commit to one final event or action for your story. Your story may have many exciting important events, but you need to choose one good scene to encapsulate your story's resolution. Make sure this scene makes sense as a final moment of the story and allows you to neatly tie up your story threads. Finally, your end scene needs to hold significance for your characters so that the reader is left with that feeling. For example, you might end your story with a scene that presents the aftermath of a major decision that resolved your story's conflict.

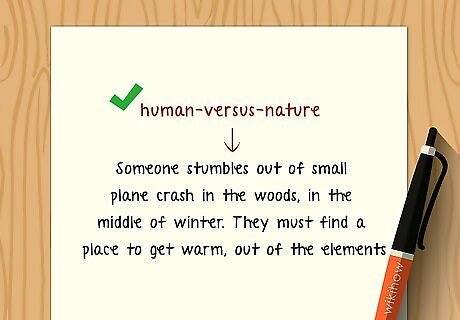

Figure out the main conflict in your story. Most story conflicts will either be person vs. person, person vs. nature, person vs. society, or person vs. themselves. Your final scene should resolve this conflict, whether your characters get what they want or not. This resolution should have an impact on your reader in order for your story to be effective. Ask yourself these questions to figure out which type of conflict you're using: Are the characters in your story fighting against nature? Against each other? Against themselves (an internal or emotional battle)? An example of human-versus-nature conflict would be someone stranded in the woods in the middle of winter. They must find a place to get warm, out of the elements.

Explaining the Journey

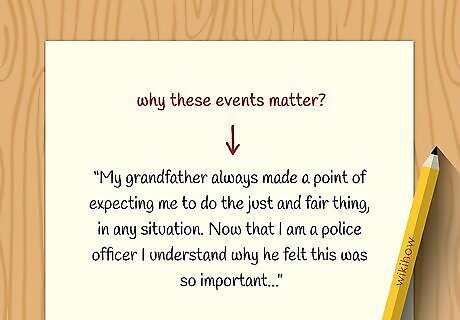

Write out a reflection about the significance of the events of the story. Consider why these events matter. What should the reader take from your story? What themes, ideas, or arguments are you trying to portray? You don't want to tell your reader these things directly, but you need to show them through the events, actions, and dialogue in your story. You might write, "My grandfather always made a point of expecting me to do the just and fair thing, in any situation. Now that I am a police officer I understand why he felt this was so important..."

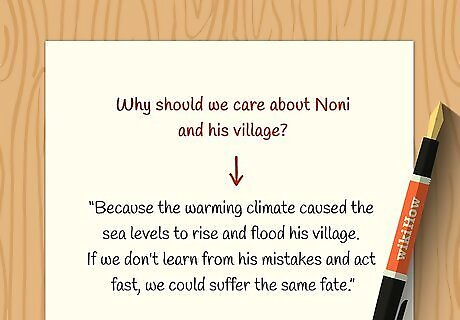

Ask the “So What?” question. Reflect on the importance or relevance of your story to the reader. Why should a reader care about your story? If you can answer this question, then review your story to see if the sequence of actions you have chosen would lead a reasonable reader to your answer. For example: "Why should we care about Noni and his village?" "Because the warming climate caused the sea levels to rise and flood his village. If we don't learn from his mistakes and act fast, we could suffer the same fate."

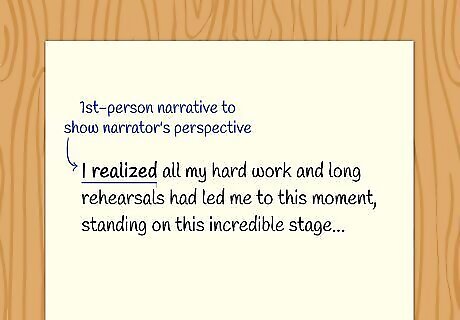

Use 1st-person narrative voice to present ideas from the narrator's perspective. A 1st-person perspective allows a close telling of the story because the speaker is involved in the events. Whether the “I” in the story is you (the writer) or the voice of a character you have created, you can simply speak directly to the reader. However, keep in mind that the story should stay very close to the character who is telling it, recounting only information they would know. For example: "I realized all my hard work and long rehearsals had led me to this moment, standing on this incredible stage..."

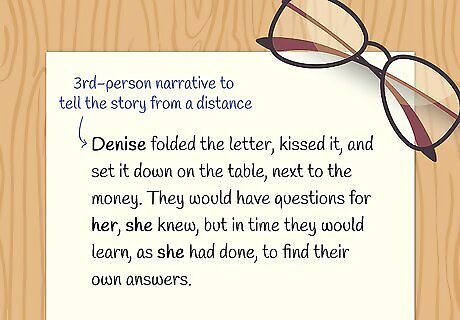

Use the 3rd-person narrative voice to tell your story from a distance. You can have another character or a narrator voice speak for you and convey the importance of the story. This allows you to inject more of your own interpretation into the story because there's some distance between the characters and the narrator. For example: "Denise folded the letter, kissed it, and set it down on the table, next to the money. They would have questions for her, she knew, but in time they would learn, as she had done, to find their own answers."

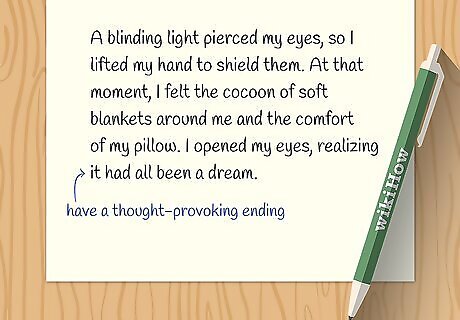

Write a “conclusion” section for your story. How you write your conclusion will depend on your genre. However, all good story endings share one element: they leave the reader with something to think about. Your reader should come away from the story thinking about the important themes of your story and it's significance. For a personal or academic essay, your conclusion could take the form of a final paragraph or set of paragraphs. If you are working on a sci-fi novel, then the conclusion might be an entire chapter or two. Don't end with common cliche endings, which will disappoint your reader. For example, don't end your story like this: "A blinding light pierced my eyes, so I lifted my hand to shield them. At that moment, I felt the cocoon of soft blankets around me and the comfort of my pillow. I opened my eyes, realizing it had all been a dream."

Identify the larger connection or pattern to the events in your story. Consider how the events flow one after the other, creating a narrative arc. Thinking about your story as a journey—where you or your main character ends up in a different place, somehow changed from the beginning—will help you see the ways in which your story has its own unique shape, and will help you find an ending that feels right.

Using Action and Images

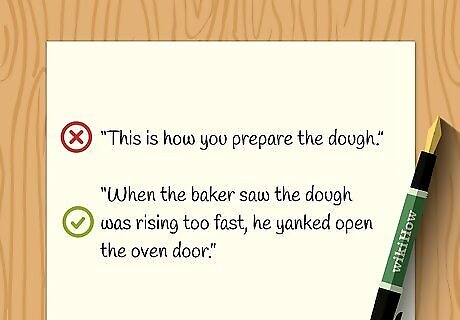

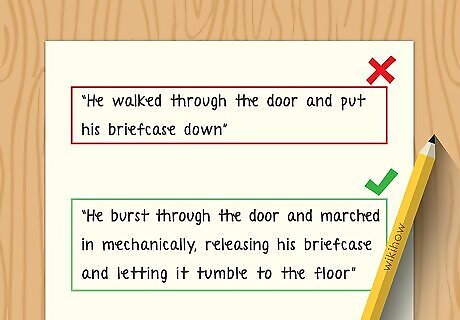

Use action to show (not tell) what is important. We know that stories full of action, whether written or visual, appeal to all ages. Through physical action you can also communicate the larger meaning and importance of your story. For example, if your story ends with the heroine saving the village from the dragon, you could have a warrior giving over his prized sword to her. Without even having any dialogue, you still show the reader that this is significant.

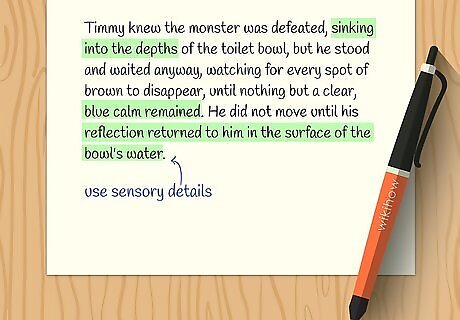

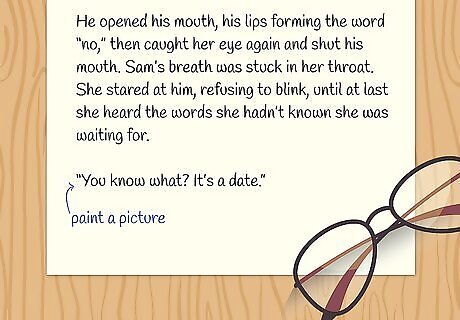

Build your ending with description and sensory images. Sensory details connect us emotionally to the story, and much good writing uses imagery throughout. However, by using rich, sensory language to paint word pictures in the final part of your story, you will leave the reader with depths of meaning. For example: "Timmy knew the monster was defeated, sinking into the depths of the toilet bowl, but he stood and waited anyway, watching for every spot of brown to disappear, until nothing but a clear, blue calm remained. He did not move until his reflection returned to him in the surface of the bowl's water."

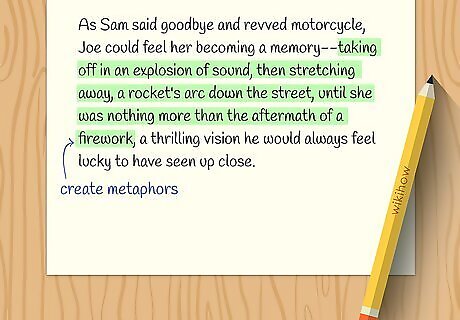

Create metaphors for your characters and their goals. Leave clues in your story for the reader/viewer to build an interpretation. People enjoy stories they can “wrestle” with and think about after reading. You don't want to make your story so confusing that a reader cannot make sense of it, but you'll want to include figurative language that is not so obvious to understand. By doing so you will add interest and significance to your work. For example: "As Sam said goodbye and revved motorcycle, Joe could feel her becoming a memory--taking off in an explosion of sound, then stretching away, a rocket's arc down the street, until she was nothing more than the aftermath of a firework, a thrilling vision he would always feel lucky to have seen up close."

Select a vivid image. Similar to using action or sensory descriptions, this approach is particularly useful when telling stories within an essay. Think about the mental picture you'd like to “haunt” the reader with—some visual picture that can capture what you feel is the essence of your story—and leave that for the reader at the end.

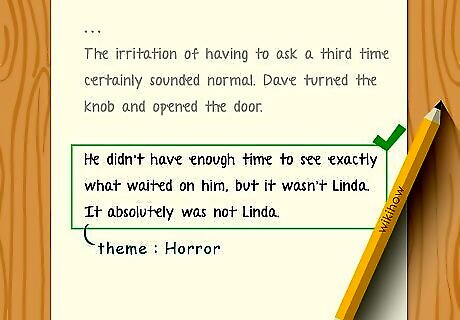

Highlight a theme. You might be working with a number of themes, particularly if you're writing a longer story, such as a history-based essay or a book. Focusing on a specific theme or motif through images or the actions of a character can help you create a structure that is unique to your story. This approach is particularly useful for open-ended stories.

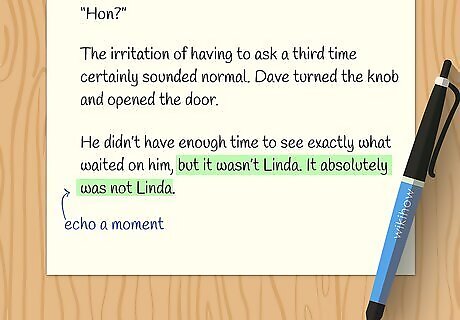

Echo a moment. Similar to highlighting on a theme, you can choose a particular action, event, or emotional moment from within your story that feels most meaningful, and then “echo” that in some way—by repeating the moment, by returning to it and reflecting or expanding on it, etc.

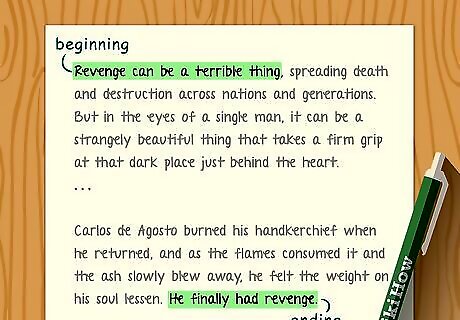

Return to the beginning. Similar to highlighting a theme and echoing a moment, this strategy means ending your story by repeating something you introduced in the beginning. This is commonly known as a “frame” or “framing device,” and it can offer shape and meaning to a story. For example, if your story begins with a person looking at a leftover piece of cake, but refusing it, end it with the same person looking at the cake (or a different one). If they overcame anorexia, you could have them eat the cake.

Following Logic

Review the events of your story to see how they connect. Remember that not all actions carry the same importance or connection. You'll use different actions and events in your story to convey different themes and messages about your story and characters. It's important that every event you include is relevant to your story and its ending. However, they do not all need to be completed or successful, as your character will likely experience failure. For example, Homer's "The Odyssey” the main character Odysseus attempts to go home a number of times and fails, encountering monsters along the way. Each failure adds excitement to the story, but what he learns about himself ends up being more important. When he does eventually make it home, his accomplishment holds more meaning because of all his failures.

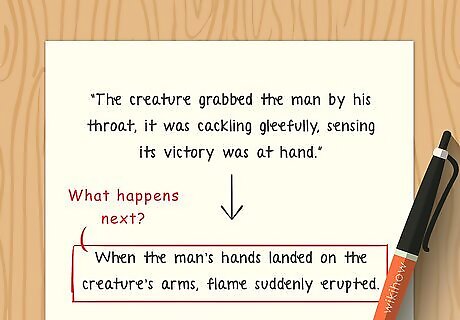

Ask yourself: “What happens next?” Sometimes when we get too excited (or too frustrated) about a story we're writing, we can forget that events and behaviors, even in a fantasy world, tend to follow logic, the physical laws of the universe you're imagining, etc. Often getting to a good ending is as easy as reflecting on what would logically happen in a situation. Endings should make sense based on what has happened earlier.

Ask yourself: “Why are these events in this order?” Review the sequence of events or actions in the story, then question actions that seem surprising in order to clarify the logic and flow of your story. For example, if your characters come across a secret doorway to a fantasy land while looking for their lost dog, return to the dog at the end. Let them visit the fantasy land, then have them find their lost dog at the end.

Imagine variations and surprises. We don't want stories to be so logical that nothing new happens in them. Think about what would happen if a certain choice or event were slightly changed--and definitely include surprises. Check to see if you have included enough surprising events or actions for your reader. For example, your readers might be bored by a character who wakes up, goes to school, comes home, and goes to bed. Let something new and surprising happen. Have her come across a strange package on her doorstep with her name on it.

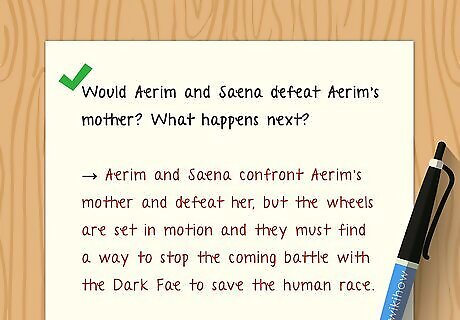

Raise a question based on where the story has brought you. Review what you have learned from the events, evidence, or details you have arranged. Think about—and then write about—what is missing, which problems or concerns are still not addressed, or what questions arise. Endings that reflect on questions can invite the reader into deeper thinking, and most topics—if pursued through logic—will lead to more rather than fewer questions. What new conflicts, for example, now await your heroes now that the monster has been destroyed? How long will the kingdom remain at peace?

Think like an outsider. Whether it is a true story or imagined, re-read your story from an outsider's perspective, and think about what would seem logical for a person reading the story for the very first time. As the writer of the story, you might feel particularly excited about an event involving one of your characters, but you should remember that a reader outside of your own head might have a different feeling about which part of the story is most important. Having some distance from your story will help you consider it more critically.

Comments

0 comment