views

In Bongaigaon, a middle-aged businessman tells me that he is upset with petrol prices and how the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has handled the Goods and Services Tax (GST), but he has no choice but to vote for the BJP-supported Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) anyway. When I ask him to explain, he says, “If the Congress alliance comes to power, then the mullahs will rule over us.”

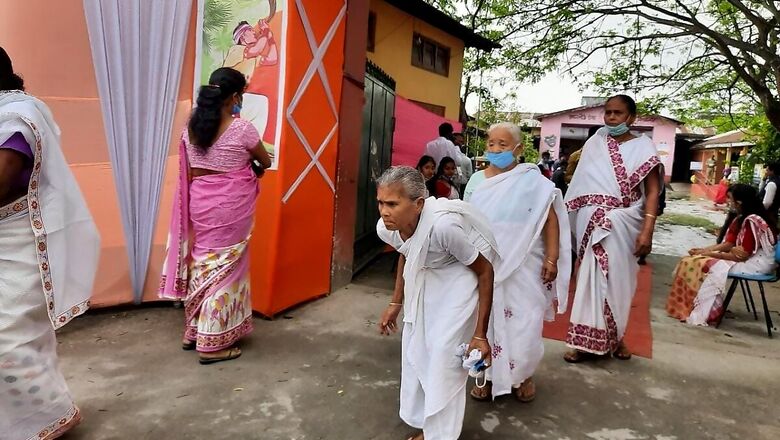

This sort of polarized language is unmissable across Lower Assam, which is voting on Tuesday in the third and final phase for the 40 remaining seats. Irrespective of how well or poorly the current government has fared on the policy front, electoral choices are almost completely a function of one’s religious identity—with Hindus supporting the BJP and Muslims supporting the Congress alliance.

In these constituencies, it is a direct, albeit polarized, contest between the two major alliances, led by the BJP and the Congress. Few people speak of campaigns, poll promises, issues or policies of the respective parties. And, predicting who will win largely boils down to understanding the demographic composition of the constituencies here.

None of this means that voters do not have legitimate grievances with the current government or the opposition. However, all these concerns take a back seat with respect to religious identity.

Demographic & electoral arithmetic

The Lower Assam is the only region where the Congress-led main opposition alliance (or Mahajot) has received more votes than the ruling BJP-led NDA in the state in every election, be it Assembly or Lok Sabha elections. The Muslim population is very high in Lower Assam, followed in numbers by ethnic communities like Bodo-Kachari, among others. However, with the Congress and Badruddin Ajmal’s All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF) contesting separately in the past, the BJP had won some seats in this region. For example, in Bilasipara East, the BJP won the seat with 35 per cent votes in 2016 while the combined vote share of the Congress and the AIUDF was 58 per cent.

ALSO READ| Why Upper Assam Matters: Whoever Wins it, Has the Upper Hand

Another important point to consider is that despite the dominance of the BJP in the state, the NDA could not win more than 15 out of the 40 Assembly seats in Lower Assam in 2016 election. Similarly, in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the NDA was leading in just 12 Assembly seats.

The Bodoland politics

In this Assembly election, the Bodoland areas, largely situated in the North Bank of Brahmaputra river in Lower Assam, comprising districts of Kokrajhar, Chirang, Darrang, Bongaigaon, Baksa, Nalbari and Udalguri, would play a decisive role in the formation of the new government in Assam. Before this election, the Bodoland People’s Front (BPF) was the sole political party from the region; however, the rise of the United People’s Party Liberal (UPPL) in the 2020 Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) election—it is now an alliance partner of the BJP— has made the 2021 electoral battle very interesting.

Both parties claim to truly represent the 27 per cent Bodo population in this region. However, to understand the politics in this region, we have to go back in time. The long history of Bodo politics is rooted in the All-Bodo Students Union (ABSU) movement. The ABSU was formed in 1967 with a demand for a separate state for the Bodos within the Indian territory to protect the ethno-cultural identity of Bodos.

In late 1970s and 1980s, when Assam witnessed a mass movement led by the All Assam Student Union (AASU) and later by the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), the Bodo youth under the banner of the ABSU participated and supported the movement, which demanded detection and eviction of foreign nationals from the state.

The formation of the new AGP government in 1985 had raised the hopes of Bodos for fulfillment of their long-standing demand; however, they soon got disenchanted with the incumbent government. In 1987, the ABSU led the agitation for a separate homeland for the Bodos within India. This movement led to the first Bodo accord, signed between the central government, the state government and the ABSU-BPAC (Bodo People’s Action Committee) in 1993. It led to the formation of the Bodoland Autonomous Council (BAC), a body for self-rule for Bodos on the northern banks of the Brahamputra. However, demands of the Bodos remained unmet. This dissatisfaction led to the emergence of the extremist groups, the Bodo Liberation Tigers (BLT) and the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB), in mid 1990s. Subsequently, law and order became a major issue due to the activities of these extremist groups in the Bodoland areas, leading to massive violence against non-Bodos.

In 2003, the new Bodo Accord was signed between the central government, the state government and the BLT (led by Hagrama Mohilary). This accord agreed to create a self-governing body, the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC), in Bodo areas of Assam. The Bodo accord paved the way for people who had gone underground to participate in elections. The members and sympathizers of the underground groups first contested as Independent candidates in the 2006 Assembly election and as BPF members 2011 onwards. This brought some peace and stability to the region.

ALSO READ| Assam Elections: Why Stakes Are High for BJP in Bengali-speaking Barak Valley

The region, however, has been marked by sporadic incidents of violence, between Bodos and the Muslims, underlying the simmering tensions between the two communities. In 2012, it was alleged that Bodos burnt the houses of Muslims in Gossaigaon. The incident was a turning point and many believe Muslims since then have been supporting the AIUDF while Bodos have rallied behind the BPF.

In the last two Assembly elections, the BPF won all the 12 seats. This time too, the party is contesting on all 12 seats (however, one candidate backed out after final nomination) as an alliance partner of the Mahajot. A simple addition of the votes in favour of the Mahajot parties in the last few elections would suggest it is a cakewalk for the BPF, but the ground reality is different. Many BPF candidates are facing severe anti-incumbency, having served as MLA for two or even three terms. Some Bodos I interacted with were not very enthusiastic about the BPF candidates and said they do have a choice this time, in the UPPL contestants.

The BPF, therefore, is banking on support from the Muslim community as a result of the Mahajot alliance, which also includes AIUDF. However, getting support from Bodos and Muslims, together, would be a big challenge for BPF leader Hagrama Mohilary, given the bitter past. The arithmetic on paper might favour the BPF, however it is the chemistry between parties that would seal the future of BPF candidates. Muslims are willing to support the BPF because they don’t have a choice, but will the Bodos continue to support the BPF this time? We would know the answers only on May 2.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment